“Diversity is realism”says Kate Elliott

In anticipation of the forthcoming Sirens conference (October 8–11, 2015 in Denver, CO), Faye Bi interviews Guest of Honor Kate Elliott.

FAYE: What fascinates me most about epic fantasy—as someone who majored in anthropology in college and loves learning about new cultures—is the worldbuilding process. You’re essentially constructing a new world, and with that, new countries and histories and customs. What is your research process like? What comes first, the details or the big idea? More importantly, since we’d all love to see more diversity in our fantasy, what is your advice for portraying cultures inspired by non-Western nations?

KATE: What comes first for me is an image of a character in a landscape, like a brief clip from a film. Often the landscape or backdrop seen in the image is based on material I’ve been reading about at some point in the last few years that has wormed its way into my subconscious. Other times the backdrop might initially be fairly generic and the most I immediately know about it is what technology level the story world will have.

Based on that image I may choose to push further into a research area I’ve already started or I may consciously think about where I want to go for the story in terms of the geographies and cultures I want to explore. I have world built “analog” cultures, which I define as “X country/history only with different names and some altered history.” I’ve also created cultures complete in themselves, unique to their space just as every culture on Earth has a unique cultural space, however small or large that space may be.

At this point in my process I will do a certain amount of reading and researching. This stage comes before the writing starts, and usually it happens while I am writing another novel. The appeal of a “side project” is strong; it’s like an illicit escape from the project you’re supposed to be working on, and the Crossroads Trilogy, the Spiritwalker Trilogy, and Court of Fives all started life as me sneaking away from a deadline to begin creating a new world. In fact, at the time of writing this answer (June 2015) I have three secret projects tugging at my skirts, one contemporary SFF and two space opera/SFs. The SF focus of these projects probably isn’t surprising considering I am currently writing two fantasy trilogies (Court of Fives and Black Wolves).

As I continue to do bits and pieces of research I will also poke at an opening scene and start some very discreet and sketchy outlining of plot. Bear in mind that no one writes exactly the same way. For me, the intersection between setting and character has always been the most important element of developing a story because the two unfold at the same time.

I do not create a setting and then place characters in it. A story kernel doesn’t come alive for me unless I have a human story to hang my hat on. That is, I have to imagine a character in a situation that has an inherent emotion or urgency or conflict that engages my passion to explore it further.

Contrariwise, I do not come up with characters and then create a setting for them.

As a brief aside: I know writers who “discover the world as they write” and those who start with a notebook already full of details. There is nothing wrong with either of these methods or any other: Writers need to figure out what works for them.

In my case, because of the way I personally integrate culture and character in my mind, I can’t create a character and story first and then figure out where it is set.

For me, people exist within a cultural space. They have beliefs, expectations, habits, and knowledge based on the micro- and macro-culture(s) they live in, and in my opinion a character is never truly created without some kind of context. A character developed before a setting has what I’ll call “invisible context,” one the writer may not be aware inhabits the character. With each choice we make about a character we invoke context even if we don’t intend to.

Let’s say I want to write a story about a young woman who is unexpectedly and against her will required to marry a man who is a stranger to her. Some may recognize the seeds of Cold Magic in this description. But look at a few of the assumptions embedded just in that unremarkable and trope-ridden sentence: That marriage exists in this culture, that a person may be forced into marriage, that people don’t need to know each other which means someone besides the two people involved are arranging the marriage. A few things we don’t yet know are whether marriage, in the culture, is exclusively between men and women, whether the male partner can likewise be required to acquiesce to a marriage he may or may not wish for, what group or individual has the power to enforce their will in this matter, and what it gains them to do so.

All of these are part of the culture that gets built around characters and an action.

As for details versus big idea, I suppose that at the deepest level the big idea comes first but for me it is discovering the details that makes a culture come alive and feel real, because it is the details of our own lives that we take most for granted which immerse us in our day to day existence.

In Cold Magic, for example, the extended greeting between people comes from my research into the culture of Mali, where acknowledging others is more important than (for example) getting somewhere “on time.” In Court of Fives a small detail like whose carriages are curtained and whose aren’t is an important detail: women from the highborn Patron class travel through the city “veiled” by light curtains on their carriages while Patron men go about visible to all, as do all Commoners regardless of gender since their concept of privacy is different from the people in the Patron class. A detail like this reveals a great deal about class, gender, and social mores, and the readers learn something about the main character Jes’s father by noticing which rules he adheres to even though he is not himself of highborn Patron birth.

For that matter, back in the day every time I read an SF novel set in the future in which women changed their names to that of their husbands I knew the writer probably wasn’t really thinking through societal change but just tacking a very specific set of cultural expectations onto their stage-set. It’s not that it might not happen (I think C.J. Cherryh deals with this in a thoughtful way in her Union/Alliance universe books in terms of alliances between spacer families), but that in these cases “custom” isn’t actually being examined; it’s just an unthought-through assumption that the whole world and history now and forever hews to the fictional universe depicted in Leave it to Beaver.

From there on out (returning to my research process) I do as much research as I have time for. I seek out general works to familiarize myself with a general knowledge base, then branch into academic work and, where possible, what people actually from that culture say about themselves and, in historical cases, wrote (usually filtered through translations). When I’m creating a world like Crossroads or Court of Fives I focus on an amalgamation of elements to create a foundation, usually people’s understood relationship to their cosmos, and build outward from there. Once I start writing the rough draft I continue to read (and possibly read even more heavily) because I discover and make up world elements as part of the writing. I often figure out fairly major world building elements in the course of writing the first draft because oftentimes characters’ actions, or the choices forced upon them, reveal the most interesting details and challenges of their world.

The process of creation is the creation, if you see what I mean.

As for advice for people seeking to write outside the culture(s) they know, I guess I would cautiously say a couple of things.

- I’m not an expert and I have made and will continue to make mistakes. Own your mistakes. Learn from them. Listen to others more than you talk yourself.

- Make room for and try not to take space from people whose voices are more marginalized than your own. Listen.

- Be humble. Be respectful. If you are going to research a culture that is not your own, listen to the voices from that culture, don’t just seek out outside views of the culture whose analysis is more comfortable for you. Ask politely, and if people don’t have time for your questions, then retreat gracefully. If they do have time, thank them and really, truly listen to what they have to say.

- No culture is monolithic. Individuals within a culture do not hold the same views and beliefs. People can have multiple ways of understanding themselves, measured against and lived within different aspects of their lives. As in rhythm, the gaps between beats are as important as the beats. Listen.

- Ask yourself why you want to do this.

- Be aware that you will be hauling your own expectations and stereotypes down this path. I don’t think we can fully rid ourselves of this baggage but we can try to be aware of where and what some of those assumptions are and try to build around them.

- Pay attention to the details, to the elements of daily life that are often derided as trivial or too unimportant for “important” fiction. I often find the best windows into other ways of living to be the day to day experiences of the world, and the habits, interactions, languages, and rhythms that characterize people’s lives. These spaces are, after all, where most life is lived.

Diversity is realism. Furthermore, speculative fiction gives us the vastest canvas imaginable, measured only against the limits of each artist’s mind. Why build a fence when we can explore the stars?

For the rest of the fascinating, lengthy interview, visit the Sirens site.

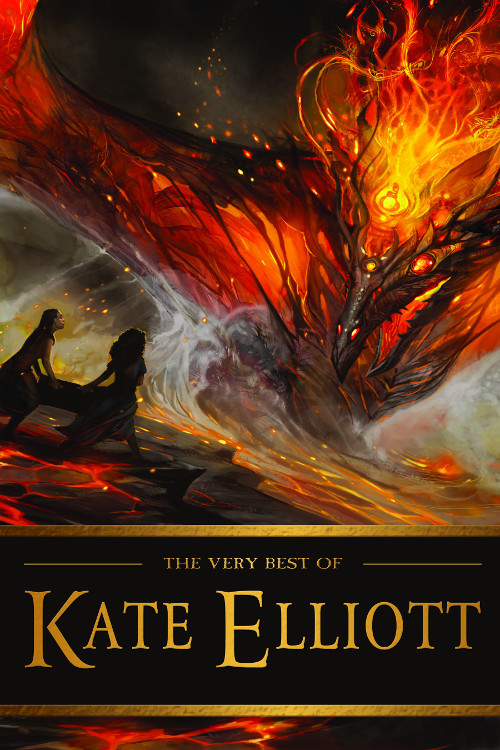

For more on THE VERY BEST OF KATE ELLIOTT, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover art by Julie Dillon.

Design by Elizabeth Story.