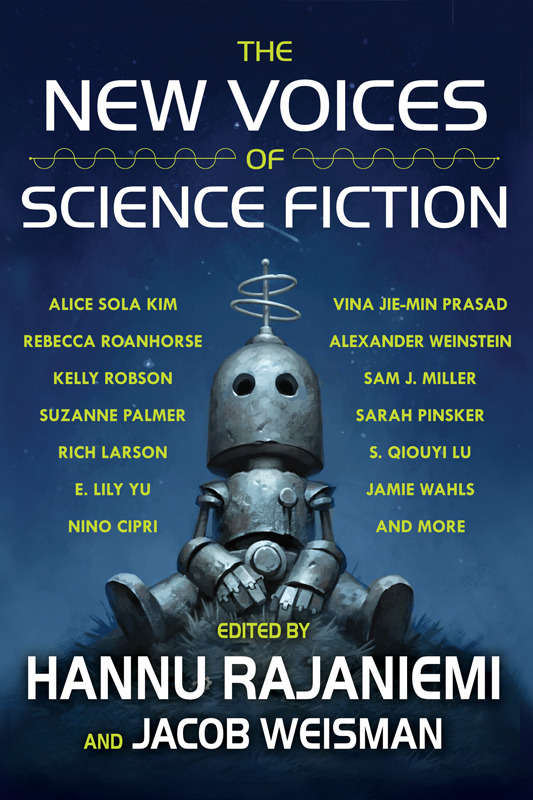

THE NEW VOICES OF SCIENCE FICTION preview: “One Hour, Every Seven Years” by Alice Sola Kim

In celebration of the recently released THE NEW VOICES OF SCIENCE FICTION, Tachyon and editors Hannu Rajaniemi and Jacob Weisman present

glimpses into the future of science fiction from several of the volume’s

magnificent tales.

One Hour, Every Seven Years

by

Alice Sola Kim

When Margot is nine, she and her parents live on Venus. The surface

of Venus, at that time, is one enormous sea with a single continent

on its northern pole, perched there like a tiny, ridiculous top hat.

There is sea below, and sea above, rain continually plummeting from

the sky, endlessly self-renewing.

When

I am thirty, I won’t have turned out so hot. No one will know; from

a few feet away, I’ll seem fine. They won’t notice the dandruff,

the opalescent flaking of my chin. They won’t know that I walk hard

and deliberate, like a ’40s starlet in trousers, in order to

compensate for the wobbly heels of my crummy shoes. They won’t see

past my really great job. And it will be a great job, really. I will

be working with time machines.

When

Margot is nine, it has been five years since she has seen the sun. On

Venus, the sun comes out but once every seven years. Margot’s

family moved to Venus from Earth when she was four. This is the main

thing that makes her different from her classmates, who are just a

bunch of trashy Venus kids. Draftees and immigrants. Their parents

work at the desalination plants, the dormitory facilities; they plumb

and bail, they traverse Venus’s vast seas in ships and

submersibles, and sometimes they do not come back.

To

her classmates, Margot will never be Venusian, even though she’s

her palest clammiest self like a Venusian, and walks and talks like a

Venusian—with that lazy, slithering drawl. Why? First finger: she’s

a freak, quiet and standoffish, but given to horrible bursts of loud

friendliness that are so awkward, they make everyone hate her more

for trying. Second finger: her dad is rich and powerful, but she

still isn’t cool. The Venus kids don’t know it, but it isn’t

her wealth they hate. It is the waste of it. The way her boring hair

hangs against her fresh sweatshirts. The way she shuffles along in

her blinding new sneakers. Third finger, fourth, fifth, sixth,

seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth fingers, and all the toes too: in her

lifetime, Margot has seen the sun and they haven’t. Venus kids are

strong and mean and easily offended. They know there’s a thing they

should be getting that they’re not getting. And

that the next best thing to getting something is no one in the whole

world getting it.

When

I am thirty, I will have gotten my first boyfriend. He’ll be a

co-worker at the lab and I won’t have noticed him for the longest

time. Big laugh, right? You would think that, as some nobody who

nobody ever notices, I’d at least be the observant one by default,

the one who notices everyone else and forms complex opinions about

them, but, no, I will be a creature spiraled in upon myself, a shrimp

with a tail curled into its mouth.

Late

night at work, a group of people will be playing Jenga in the lounge.

The researchers love Jenga because it has the destructive meathead

glamour of sports but only a fraction of the physical peril. Anders

will ask me if I want to play and I’ll shake my head, hoping it

looks like I’m too cool for Jenga but also bemused and tolerant,

all of this hiding the truth, which is that I am terrified of Jenga.

I’m afraid of being the player who causes all of the blocks to

fall. Because that player is both appreciated and despised: on the

one hand they absorb the burden of causing the Fall, thus relieving

everyone else of said burden, but on the other hand, they are

responsible for ending the game prematurely, killing all the fun and

potential, not to mention the Jenga tower itself—the spindly

edifice that everyone worked so hard together to create and protect.

The

guy who will be my first boyfriend will push a block out without any

hesitation. He won’t poke at it first, he will go straight for the

block, and I will watch as the tower wobbles. It won’t fall. As he

takes the dislodged block and stacks it on his pile, he will make eye

contact with me, a carefully constructed look of surprise on his

face—mouth the shape of an O, eyebrows pushing his forehead

into pleats.

When

Margot is nine, the sun comes out on Venus. Her classmates lock her

inside a closet and run away. They are gone for precisely one hour.

When her classmates finally come back to let Margot out, it will be

too late.

When

I am thirty, I will have been at my great job, the job of working

with time machines, long enough to learn their codes and security

measures (I’ve even come up with a few myself), so I will do the

thing that I didn’t even know I was planning to do all along. I

will enter the time machine, emerging behind a desk in the school I

attended when I was nine. Water droplets will condense on the walls.

There is no way to keep out the damp on Venus. The air in the

classroom will taste like the air in a bedroom where someone has just

had a sweaty nightmare. I will hide during all of the ruckus, but

don’t worry: I will work up the courage. I will stand and open the

closet door and do what needs to be done. And I will return!

For more info about THE NEW VOICES OF SCIENCE FICTION, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover art by Matt Dixon

Cover design by Elizabeth Story