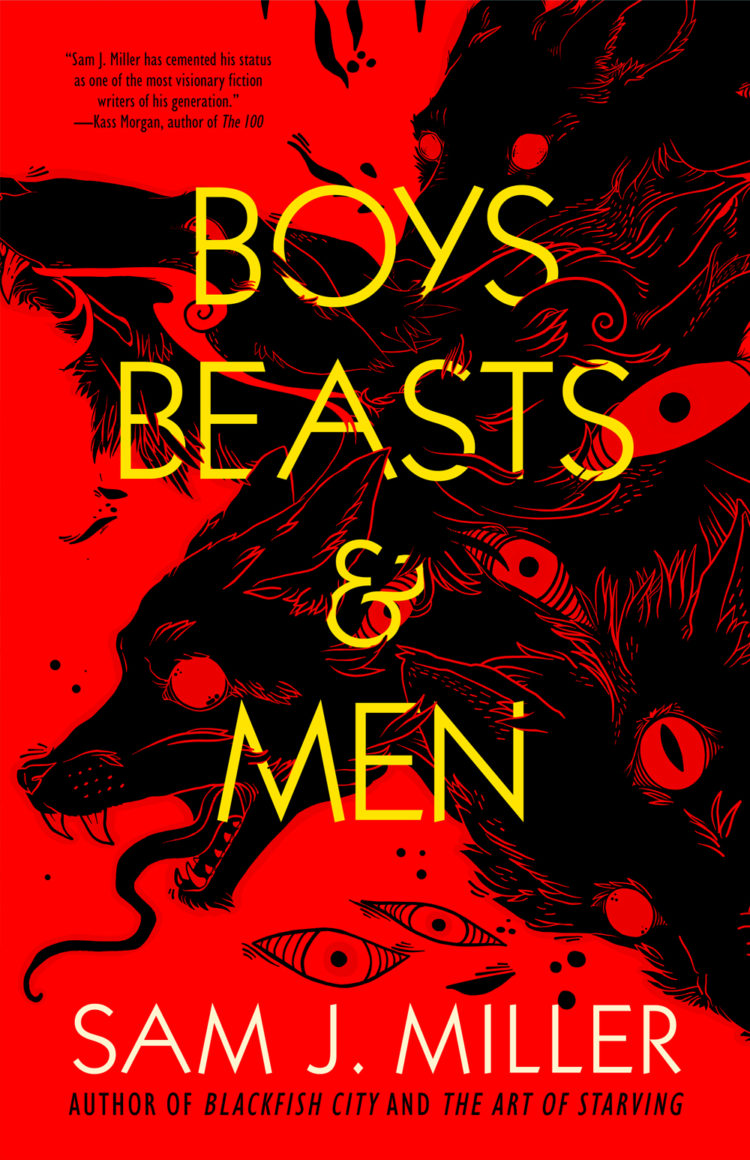

BOYS, BEASTS & MEN by the award-winning Sam J. Miller preview: “Angel, Monster, Man”

In celebration of the release of Sam J. Miller’s debut collection BOYS, BEASTS & MEN, Tachyon presents glimpses from the new collection.

In these stories Sam J. Miller writes about people on the margins and in transition, both capturing a sense of uncertainty and horror while immersing us in these worlds with sensitivity and care.

—Carrie Vaughn, author of The Immortal Conquistador

Design by Elizabeth Story

Angel, Monster, Man

by

Sam J. Miller

“Fuck Hemingway,” Pablo said sourly. “We’re the real lost generation.”

“Except we don’t have a Hemingway,” I said.

“Who the hell wants a Hemingway?”

“A Hemingway has its advantages,” I said. “As is evidenced by the fact that we know his name twenty years after he died, and all our friends are forgotten as soon as they hit the earth.”

Pablo hadn’t heard, wasn’t listening. His mind was on our enemies, as it so often was. “Did you guys hear that the federal government sent inspectors to New York, and they expressed concern over the high number of homeless people with AIDS, and the city said not to worry, they were dying so fast there would be no visible increase, certainly nothing to impact tourism?”

“Yeah,” I said. We had all heard it—a rumor, possibly hopefully a fiction, but all the worse for that, for the effortless way it encapsulated our world.

“I’m against the death penalty,” Pablo said. “But those motherfuckers should be shot.”

We sipped coffee, said nothing, our eyes following a swirl of dead leaves and dark thoughts.

I firmly believe the idea entered all three of our brains at the same exact time, like Tom Minniq wasn’t so much a figment of our imagination as a wandering soul who got lost on the way to reincarnation and instead of entering a woman’s womb ended up in the brains of three grief-broken gay boys.

“No one cares about a pile of dead gay artists,” Pablo said, and something in his tone made us all three scooch our chairs closer to the table—something hopeful and inspired, something dangerous and secret. “People can’t identify with statistics.”

“They need one face,” Derrick whispered, the fraught tone leaping from Pablo to him like the wind passing a shudder from one tree to the next.

“One name,” I said.

“A composite,” Derrick said. “A synthesis of every brilliant artist who died before they could make their mark.”

“A collective pseudonym,” I said. “For every writer in our lost generation. If we don’t have a Hemingway, we’ll invent one.”

“Tom,” Derrick said. “A good, simple, macho name.”

“Tom Minniq,” Pablo said, and spelled it for us. “Minniq was an Eskimo boy who the Natural History Museum brought to New York City along with his father and ten kinsmen, all of whom but Minniq died from pneumonia almost immediately. Separated from his tribe. Stranded among savages who thought he was the subhuman one. I read, you two.”

Derrick inclined his head.

“Also, he needs to be a little ethnic,” Pablo said. “Minniq sounds . . . other. People who aren’t white die too, you know.”

They came easy: the mechanics of fraud, the logistics of forgery. We spent all day on the patio bouncing ideas around, and went inside when it got dark to fill up pieces of paper. Identifying all the problems likely to pop up. Finding ways around them.

Being a criminal is not so different from being an artist. Both depend on the same degree of audacity. Derrick would handle the business end: submissions and edits, pitches and contracts. I would handle the work itself, the unread stories and unfinished novels gleaned or inherited or rescued or stolen.

Finding a face and body for our Frankenstein proved more difficult. Fifty years earlier, we could have gotten away with a single blurry picture, or said he was a recluse who feared photographs would steal his soul. Our Tom had to be one of us: an urban butterfly, a creature of Saturday night dancing and Fire Island beach parties, and photo-shyness was incompatible with our pride and vanity.

Pablo had the solution. From his bag, he pulled a thick folder of the late Joe Beem’s photos and spread them on Derrick’s coffee table, sweeping aside the Chinese take-out containers that had blossomed like mushrooms at some point in the preceding hours.

“There,” he said, pointing to a black-haired dancing boy with his back to the camera, “and there,” another boy, shirtless on the beach, black hair cut the same way, “and this one,” and if you looked at them right you could see it, the rough outline of the same man in dozens of different ones. “We find photographs of men who meet this general type—average height, black hair, muscular build, stubble—and that’s him. I can work them in the darkroom to blur out the parts that don’t fit, or add distinguishing marks. Jug-handle ears, maybe, or a birthmark over his jugular.”

“It’s perfect,” Derrick said. “No author photos, no glossy head shots. Candids, glimpses. A life lived out of the public eye.”

Because to succeed as myth, Tom had to be dead. Otherwise the charade became too complicated to maintain. And who would know, in this city where the dying stacked up faster than firewood, that this one particular name in the long litany had never been an actual person? Who could prove that Tom Minniq was any more fictional than the rest of the gay men and women who fled horrific far-off small-town lives and reinvented themselves upon arrival in our city, sometimes changing their names and cutting all family ties and spinning the most ridiculous lies to cover them?