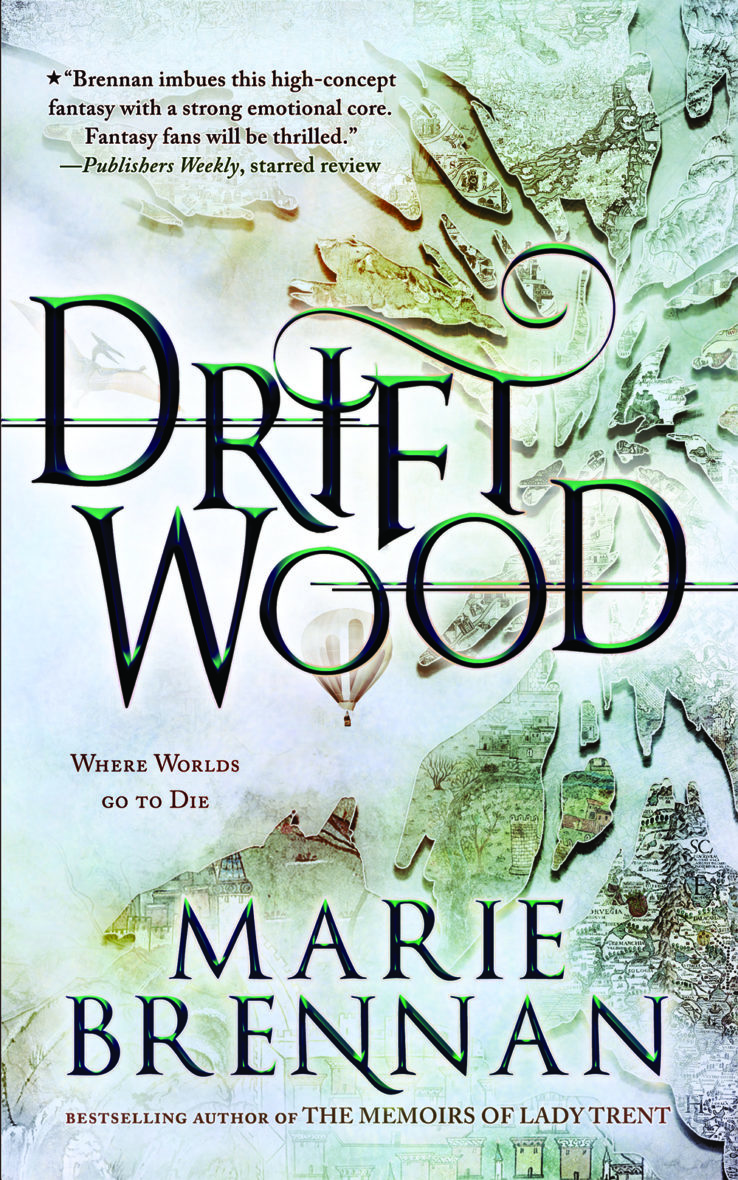

DRIFTWOOD by Marie Brennan preview: “Into the Wind”

In celebration of the release of Marie Brennan’s DRIFTWOOD, Tachyon presents glimpses from the book that is “An exciting delve into a conglomerate land filled with magic and mystery.” (Kirkus)

Into the Wind

by

Marie Brennan

The tenements presented a blank face to the border: an unbroken expanse of wall, windowless, gapless, resolutely blind to the place that used to be Oneua. Only at the edges of the tenements could one pass through, entering the quiet and sunlit strip of weeds that separated the buildings from the world their inhabitants had once called home.

Eyo stood in the weeds, an arm’s length from the border. The howling sands formed a wall in front of her, close enough to touch. They clouded the light of Oneua’s suns, until she could barely make out the nearest structure, the smooth lines of its walls eroded and broken by the incessant rasp of the sands. And yet where she stood, with her feet on the soil of Gevsilon, the air was quiet and still and damp. The line between the two was as sharp as if it had been sliced with a razor.

“I wouldn’t recommend it, kid.”

The voice was a stranger’s, speaking the local trade pidgin. Eyo knew he was addressing her, but kept her gaze fixed on the boundary before her, and the maelstrom of sand beyond. She didn’t care what some stranger thought.

People came here sometimes. Not the Oneui—not usually—but their neighbors in Gevsilon, or other residents of Driftwood looking for that rare thing, a quiet place to sit and be alone. The winds looked like their shrieking should drown out even thought, but their sound didn’t cross the border, any more than the sand did. As long as you didn’t look at the sandstorm, this place was peaceful.

But apparently the stranger didn’t want to be quiet and alone. In her peripheral vision she saw movement, someone coming to stand at her side, not too close. Someone as tall as an Oneui adult, and that was unusual in Driftwood.

“You wouldn’t be the first of your people to try,” he said. “You’re one of the Oneui, right? You must have heard the stories.”

Oh, she had. It started as a dry, stinging wind, after their world parched to dust. Then it built into a sandstorm, one that raged for days without pause, just as their prophecies had foretold. Eyo’s grandparents and the others of their town had refused to believe it was the end of the world; in their desperation, they gathered up their water and food and tied themselves together to prevent anyone from getting lost, and they went in search of a place safe from the sand.

They stumbled into Gevsilon. And that was how they found out their world had ended.

But not entirely. This remnant of it survived. And Gevsilon, their inward neighbor, had gone through an apocalypse of its own: a plague that rendered all their people sterile. There weren’t many of the Nigevi left anymore, which meant there was enough room for the Oneui to resettle. Just a stone’s throw from the remnants of their own world, and everything they’d left behind.

Of course some of them tried to go back. The first few returned coughing and blind, defeated by the ever-worsening storm. The next few stumbled out bloody, their clothing shredded and their flesh torn raw.

The last few didn’t return at all.

“Why do you lot keep trying?” the stranger asked. “You know by now that it won’t end well. Is this just how your people have taken to committing suicide?”

Some worlds did that, Eyo knew. Their people couldn’t handle the realization that it was over, that Driftwood was their present and their future, until the last scraps of their world shrank and faded away. They killed themselves singly or en masse, making a ritual of it, a show of obedience to or protest against the implacable forces that sent them here.

Not her.

She meant to go on ignoring the stranger. It wasn’t any of his business why she was here, staring at the lethal swirls of the sandstorm. But when she turned to go, she saw him properly: a tall man, slender and strong, his hair and eyes and fingernails pure black, but his skin tinged lightly with blue.

In Driftwood, people came in all sizes and colors and number of limbs and presence or lack of horns and tails. Eyo didn’t claim to know them all. But she’d heard of only one person fitting this man’s description.

“You’re Last,” she said. Sudden excitement made her tense.

His eyes tightened in apprehension, and he retreated a careful step. “I am.”

“You can help me,” Eyo said.

He retreated again, glancing over his shoulder, toward the faceless wall of the Oneui tenements, and the nearest opening past them. “I don’t think so, kid. Sorry. I—”

She stepped forward, matching him. She didn’t have her full growth yet, but she was quick and good at running; she would chase him if he fled. “You’re a guide, aren’t you? Someone who knows things, knows where to find things.”

He stopped. “I—yes. I am.”

One of the best in Driftwood, or so people said. He knew the patchwork of realities that made up this area, because he’d been around for longer than any of them. The stories claimed he was called Last because he was the last of his own world—a world that had been gone longer than anyone could remember.

Clarity dawned. “Oh. You thought I was going to ask you to go into the sandstorm?”

He gave the howling storm a sideways glance. “You wouldn’t be the first.”

Because the stories also said he couldn’t die. Eyo scowled. “Someone asked you? Who? Tell me their name. I don’t care what the storm is like; the idea of sending an outsider in there, asking them to bring back the—”

She cut herself off, but not before Last’s eyebrows rose. “Bring back? You lost something in the storm?”

“It isn’t lost,” Eyo snapped. “We know exactly where it is.”

Now she saw clarity dawn for him. “That’s why your people keep going in,” he said thoughtfully, gaze drifting sideways again. “Look, whatever it is—it may not even be there anymore. This is Driftwood; things crumble and fade away, even without apocalyptic sandstorms to scour them into dust.”

Conviction stiffened Eyo’s crest, her scalp feathers rising in a proud line. “Not this. Everything else will fall apart and die, but not—” She swallowed and shook her head. “When we are gone, this will remain.”

His shrug said he didn’t agree, but he also didn’t care enough to argue anymore. “So if you don’t want to send me into that, what do you want me for?”

Eyo smoothed her crest with one hand, as flat to her skull as she could make it. If he knew her people, he would recognize that as a gesture of humility and supplication. “I want you to help me find a way to survive the sand.”