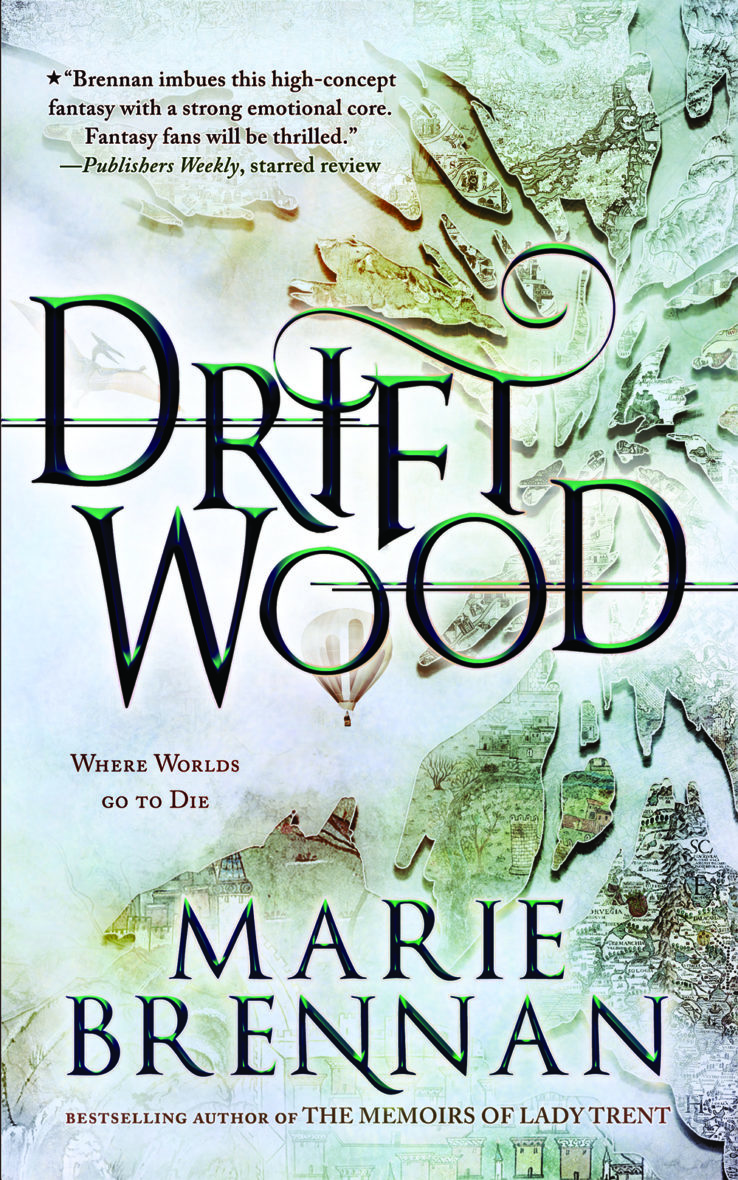

DRIFTWOOD by Marie Brennan preview: “The Storyteller”

In celebration of the release of Marie Brennan’s DRIFTWOOD, Tachyon presents glimpses from the book that is “haunting, timeless, and timely.” (Max Gladstone)

The Storyteller

by

Marie Brennan

No one know how it starts, because no one is there to see.

The amphitheater has been abandoned for ages, and for good reason. Any living creature that remains within its truncated bowl when that world’s sun rises dies . . . or disappears and is never seen again, which amounts to the same thing. As a result, it is that rarest of commodities within the Shreds: a piece of uninhabited dry land.

Not unused, though. The timeworn sandstone benches are solid enough, if not precisely comfortable, and now that someone has knocked down the creepy, insectile statues that used to stand in watch—or possibly in threat—at the top of the stands, the amphitheater is a nice enough place for all kinds of uses, from performances to markets to punishment for the remaining one-bloods of Skyless. They permit others to use the space as they please, but personally consider its open-air nature to be the next worst thing to hell.

|

Only at night, though. Throughout the day, and for a generous margin before sunrise and after sunset, the amphitheater tends to be deserted. With the differences in cycles between worlds, nobody quite wants to risk guessing wrong about what time it is—nor do they want to experiment and find out just how long the dangerous period is. And since these days only one tunnel leads from Skyless onto the amphitheater floor, and the people of Soggeny and Up-End don’t make a habit of climbing the amphitheater’s walls, there’s not a lot of traffic in or out.

Which means that as near as anyone can tell, the wreath of flowers simply appears, laid there by some unknown hand, their unfading sapphire petals shining with a faint light of their own in the darkness.

It could be for some other purpose. But the sapphire flowers with their ruby stamens come from Aic, growing like hair from the heads of the few remaining Ta-Aici, and the news—the rumor; the joke; the lie—went around Aic just a little while before. So somebody, it seems, has made an assumption.

More than one somebody. The next night, which is supposed to be a market night, the wreath has company: a tiny stone pyramid, three candles, a shoe, a blunted knife, six torn pieces of fabric. The meaning of the things left there varies, and sometimes they don’t have any beyond the personal, but the ripped cloth is clear.

In the Shreds of Driftwood, that is a sign of mourning.

After that, everybody sees the pile grow. The market goes on as it should, but other people come, too: Drifters and one-bloods alike, from farther Shreds like Pool, from the nearer parts of the Ring, even an Edger or two who happens to be close by. Some come to lay their own tokens on the floor of the amphitheater. Others come just to watch the spectacle, to murmur questions and doubts at each other.

Is it true? The whole thing is a joke. I don’t believe it anyway. Never have. This is Driftwood; we all know how it works. How can anybody be sure?

Febrenew is there before the second night ends. He keeps the latest iteration of a long series of bars called Spit in the Crush’s Eye—or rather, kept. It most recently conducted its business in an improbable cavern, carved out of solid rock beneath a stretch of viscous mud that sucks in anyone who sets foot on it. The entrances lay through the safer terrain of Nidroef and Whitewall, burrowed underground and propped up with enormous rib bones pillaged from some creature that didn’t need them anymore.

But probability has caught up with that cavern, flooding it with mud, and flooding Febrenew out. He hasn’t yet found a new home for the bar, and while the amphitheater certainly isn’t a candidate, it will do as a temporary source of profit. With so many people gathering, some of them are bound to want food and drink.

Answers, too—but unlike some of his predecessors, Febrenew is scrupulous about his gossip. When a woman asks him if he knows anything, he tells her the truth, which is that he knows no more than anyone else. But it doesn’t stop her from loitering nearby, then making periodic arcs through the amphitheater, questioning other onlookers. She’s a one-blood, her skin as dark as rich soil, hair coiled against her scalp in intricate gold-threaded knots. The sort of style people only bother with when there’s still meaning behind it. An exile from her own world, maybe; there are enough of them around.

And even Febrenew doesn’t know everyone. The Drifter community is too complicated for that, held together by its differences as much as anything else. He doesn’t know that woman, or the silent old man who takes up station at the top of the benches and sits there eating seeds, or the small, lizard-like creature that conveys through mime that it will conjure water to wash cups for him in exchange for some beer.

Nor does he know the man who approaches the growing mound of trinkets not long after the sun sets on the third night, bearing an ancient mask in his hands.