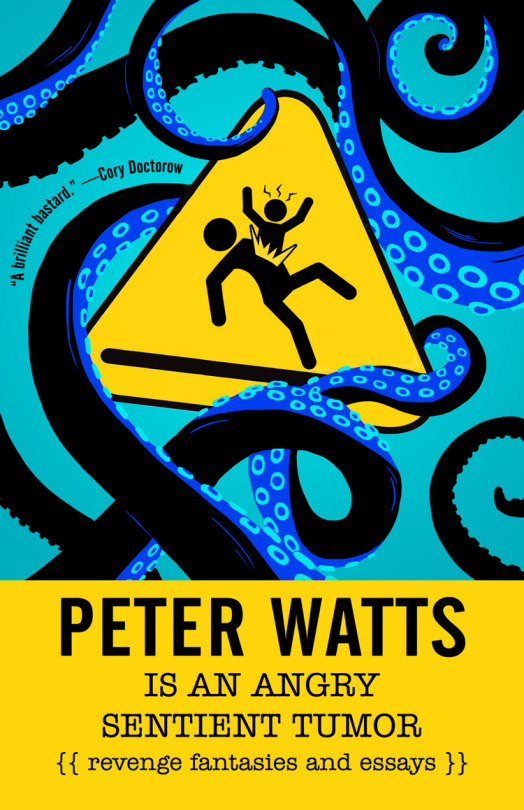

PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR preview: “Why I Suck”

In celebration for the release of the irreverent, self-depreciating, profane, and funny PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, Tachyon presents glimpses from the essay collection.

Why I Suck.

by

Peter Watts

Blog June 6, 2013

I’ve

just sat through an entire season—which is to say three measly

episodes, in what might be the new SOP for the BBC (see Sherlock)—of

this new zombie show called In the Flesh.

Yeah,

I know. These days, the very phrase “new zombie show” borders on

oxymoronic. And yet, this really is a fresh spin on the old paradigm:

imagine that, years after the dead clawed their way out of the ground

and started feasting on the living, we figured out how to fix

them. Not cure, exactly: think diabetes or HIV, management

instead of recovery. Imagine a drug that repairs the mind, even if it

can’t fix the rot or the pallor or the eyes.

Imagine

the gradual reconnection of cognitive circuitry, and the flashbacks

it provokes as animal memories reboot. Imagine what it must be like

when the sudden fresh remembrance of people killed and eviscerated is

regarded, clinically, as a sign of recovery.

This

is only the beginning of what In the Flesh imagines. It also

imagines government-mandated reintegration of the recovering undead

(“Partially-Deceased-Syndrome” is the politically-correct term;

it comes replete with cheery pamphlets to help next-of-kin manage the

transition). Contact lenses and pancake makeup to make the

partly-dead more palatable to the communities in which they once

lived. Therapy sessions in which the overwhelming guilt of

freshly-remembered murder and cannibalism alternates with defiant

self-justification: “We had to do it to survive. They blew our

heads off without a second thought—they were protecting

humanity! They get medals, we get medicated …” Hypertrophic

Neighborhood Watch patrols who never let you forget that no matter

how Human these creatures may seem now, a couple of missed

injections is all it takes to turn them back into ravening monsters

in the heart of our community …

What’s

science fiction’s mission statement, again? Oh, right: to explore

the social impact of scientific and technological change. Too

much SF takes the Grand Tour Amusement Park approach, offers up an

awesome parade of wonders and prognostications like some kind of

futuristic freak show. It takes a show like In the Flesh to

remind us that technology is only half of the equation, that the

molecular composition of the hammer or the rpms of the chainsaw, in

isolation, are of limited interest. Our mission hasn’t been

accomplished until the hammer hits the flesh.

In

the Flesh rubs your face in that impact. It rubs my face in my

own inadequacy.

Echopraxia

has its share of zombies, you see. They show up at the beginning of

the book, in the Oregon desert; through the course of the story,

various cast members wrestle with zombiesque aspects of their own

behavior. Echopraxia’s zombies come in two flavors: the

usual viral kind sowing panic and anarchy, and a more precise,

surgically-induced breed used by the military for ops with high body

counts, ops for which self-awareness might prove an impediment. Both

breeds get screen time; both highlight philosophical issues which

challenge the very definition of what it means to be Human.

Neither

really tries to answer questions like: How do you deal with the

guilt? Or How do you handle the dissonance of becoming a local

hero through the indiscriminate slaughter of rabid zombies, only to

have your son come back from Afghanistan partially-deceased with a

face full of staples?

In

the Flesh does a lot of the same things I’ve done in my own

writing. It even serves up a pseudosciencey rationale to explain the

zombie predilection for brains: victims of PDS lose the ability to

grow “gial” cells in their brains, and so must consume those of

others to make up the deficit. (I’m not sure whether this is an

inadvertent misspelling of “glial” or if the writers were savvy

enough to invent a new cell type with a similar name, the better to

fend off the nitpickery of geeks like me.) It doesn’t hold up to

rigorous scrutiny any better than Blindsight’s invocation of

protocadherin deficits to justify obligate cannibalism in my own

undead, but in a way that’s the point: they’ve taken pretty much

the same approach that I have.

The

difference is, they’ve done so much more with it.

I used technobabble to justify a philosophical debate about free

will. In the Flesh used it to show us grief-stricken parents

dealing with a beloved son after he’s taken his own life—and come

back. Side by side, it’s painfully obvious which of us used our

resources to better effect.

I

only wish I’d have been able to see that without the object lesson.

For more info about PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover design by Elizabeth Story

Icon by John Coulthart