Reviewers, bloggers, and librarians get Hugo and Nebula Award-winner Peter S. Beagle’s SUMMERLONG

Review copies of the World Fantasy Award winner and creator of THE LAST UNICORN Peter S. Beagle’s new novel SUMMERLONG are now available via NetGalley.

These copies are only for reviewers and librarians. For more details, visit NetGalley.

And while you are there, check out the other Tachyon titles for review.

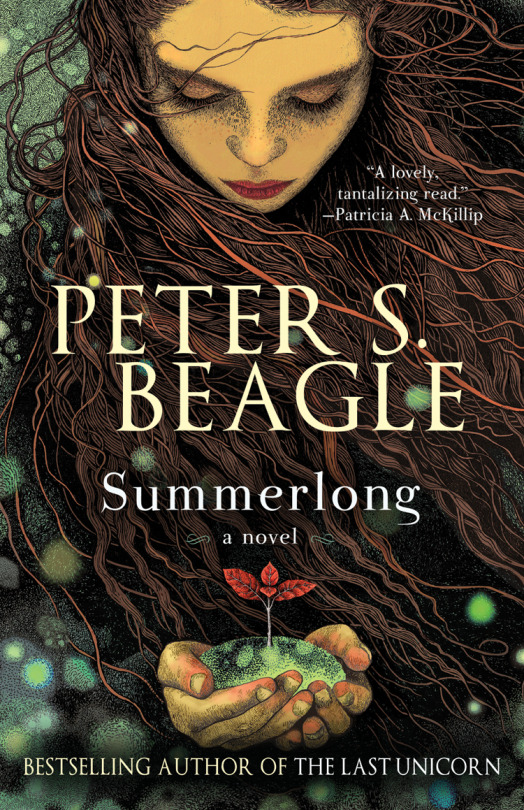

SUMMERLONG

by Peter S. Beagle

Beloved author Peter S. Beagle (The Last Unicorn) returns with this long-anticipated new novel, a beautifully bittersweet tale of passion, enchantment, and the nature of fate.

It was a typically miserable Puget Sound winter before the arrival of Lioness Lazos. An enigmatic young waitress with strange abilities, when the lovely Lioness comes to Gardner Island even the weather takes notice.

As an impossibly beautiful spring leads into a perfect summer, Lioness is drawn to a complicated family. She is taken in by two disenchanted lovers—dynamic Joanna Delvecchio and scholarly Abe Aronson—visited by Joanna’s previously unlucky-in-love daughter, Lily. With Lioness in their lives, they are suddenly compelled to explore their deepest dreams and desires.

Lioness grows more captivating as the days grow longer. Her new family thrives, even as they may be growing apart. But lingering in Lioness’s past is a dark secret—and even summer days must pass.

Praise for Peter S. Beagle

“Short story and fantasy lovers will devour these tasty tidbits that whet the appetite for more.”

—Library Journal

“[Beagle] has been compared, not unreasonably, with Lewis Carroll and J. R. R. Tolkien, but he stands squarely—and triumphantly—on his own feet.”

—The Saturday Review

“… One of my favorite writers.”

—Madeleine L’Engle, author of A Wrinkle in Time and A Swiftly Tilting Planet

“Peter S. Beagle illuminates with his own particular magic such commonplace matters as ghosts, unicorns, and werewolves. For years a loving readership has consulted him as an expert on those hearts’ reasons that reason does not know.”

—Ursula K. Le Guin, author of A Wizard of Earthsea and The Left Hand of Darkness

“The only contemporary to remind one of Tolkien.”

—Booklist

“Peter S. Beagle is (in no particular order) a wonderful writer, a fine human being, and a bandit prince out to steal readers’ hearts.”

—Tad Williams, author of The Dragonbone Chair and The Very Best of Tad Williams

“It’s a fully rounded region, this other world of Peter Beagle’s imagination…an originality…that is wholly his own.”

—Kirkus

“Not only does Peter Beagle make his fantasy worlds come vividly, beautifully alive; he does it for the people who enter them.”

—Poul Anderson, author of The High Crusade

“Peter S. Beagle is the magician we all apprenticed ourselves to. Before all the endless series and shared-world novels, Beagle was there to show us the amazing possibilities waiting in the worlds of fantasy, and he is still one of the masters by which the rest of the field is measured.”

—Lisa Goldstein, author of The Red Magician and The Uncertain Places

“Peter S. Beagle would be one of the century’s great writers in any arena he chose; we readers must feel blessed that Beagle picked fantasy as a homeland. Magic pumps like blood through the veins of his stories. Imparting passionately breathing, singing, laughing reality to the marvelous is his great gift to us all.”

—Edward Bryant, author of Cinnabar

Excerpt

They slept late, and wound up taking the noon ferry to Gardner Island, using both cars. On deck they watched for orcas, and Joanna talked about Lily. “She’s got such lousy taste in women, that’s what gets me so pissed at her. I don’t care that they’re usually grocery clerks or construction workers—hell, the lawyer was the worst of the lot—but they treat her so badly, Abe. I know, I know, she practically asks for it, and it’s her life, not my business. I know all that. It shouldn’t break my stupid heart, but it does.”

“I should talk to her,” he said. “We used to have such long, serious talks when she was little. About death and sex and dinosaurs, and why some people can raise one eyebrow and some people can’t. It’s been a while since we had one of those.”

“She always liked you.” Joanna’s voice sounded determinedly toneless. “You never disappointed her. Unlike me.”

“Come on, I never had a chance to disappoint her. I’ve been Uncle Abe almost all her life. Uncles get away with lots more than mothers. Uncles go home.”

The ferry turned slowly into the wind, approaching the island. It was a curiously warm wind, surprising Abe with its unseasonal caress, but Joanna shivered and shoved her hands deep into her jacket pockets. “Lily was born disappointed in me. They put her into my arms, and we looked at each other, and I knew right then: I’m never going to please this one, not ever. Everything she does, every dumb choice she makes, it’s all got to do with that very first disappointment. Does that sound absolutely weird?”

“No, just absolutely vain.” He put his arms around her from behind, nuzzling into her hair. “God’s sake, give the kid some credit, let her be independently dumb. You can’t be snatching all her idiocy for yourself, that’s just plain greedy. Think how dumb her father was, ditching you for a real-estate agent. It’s in the genes, cookie.”

“Don’t call me cookie,” she said automatically, but she pressed herself back against him. “I thought of a way we can prop up that saggy porch of yours. I’ll show you when we get there.” The arrival horn sounded then, and they went below to their cars.

Following the tomato-red Jaguar—her single luxury—off the dock, they paused at the lone traffic light of Marley, Gardner Island’s only real town, then turning up into the green-shrouded hills. Sixteen years. Sixteen years I’ve known I don’t belong here, and there’s still nowhere else I want to be. Somebody else … that’s another matter.

He thought about Lily as a child, playing contentedly with skeletal horses twisted out of pipe cleaners. An undertow of memory caught him there, summoning the night drive sixteen years before, and the blood that had looked so black on Joanna’s new skirt. Another girl, it would have been. Lily wanted a sister so much.

The Sound came into view at the top of the first ridge; then vanished again behind the shaggy hemlocks that had long ago replaced the logged-off pines and Douglas firs. Ahead of him, the red Jaguar handled the turns with autopilot ease, just as he did making the run from the ferry to Queen Anne Hill. He saw two deer browsing in someone’s tomato patch—they never looked up as he passed—and a family of raccoons prowling the roof of the elementary school. I wonder if they crap up there, the way they do on my beach stairs. Probably.

The last descent to the coast road always felt to him like tumbling straight into the gray sky and the gray water below. He could see her riding the brakes, as he was forever telling her not to do. He ordered himself not to say anything about it, though he knew he would. She turned left at his battered green mailbox, crept down the steep driveway—paved once again last year, and already fracturing like arctic ice in the spring—veered sharply right at the fork, and nosed the Jaguar into her favorite space under the burly wisteria vine. He parked by the woodpile, and they stood silently together, regarding his house. Turk, the neighbors’ enormous hound, dimwitted to a point of near-saintliness, came and barked savagely at them, and then settled down to insistently snuggling his head between Joanna’s knees.

Abe said, “The porch isn’t that saggy. We could go another year, easy, without messing with it.”

“What’s that thing on the roof?” She pointed to a peculiar bulge near the attic window, barely visible beneath a winter’s humus of hemlock needles. He blinked, then shrugged. “What? It’s always been there, you just never noticed it before. Doesn’t leak or anything.”

Joanna was looking at the little one-car garage, down a slight slope to the left of the house. She said, “You know, a really good spring project would be to clean out that dump so it’d be fit for a self-respecting car to live in. It wouldn’t take that long, two of us working.”

“Del, that’s where I keep stuff, we’ve been over that. That’s my reference library.” She laughed in his face, her warmly derisive, anciently bawdy Mediterranean laugh. After a moment he joined her, as he never could resist doing. “Okay, it’s my stuff library, but some of it comes in useful sometimes. I made that choice way back, keeping the car dry or my papers.”

“Well, if you ever looked at those boxes, you’d see the mildew all over them, never mind how many old bedspreads you cover them with. What’s wrong with moving them to the basement?”

He sighed. “Because that’s where I’ve got all my beer stuff—my boiler and my carboy, all my bottles and yeast and malt and everything. Give it up, Del. I know you’re right, no question, I’ll deal with it. Summer, I promise, after we get back from the rain forest.”

About to continue the argument, she caught herself and laughed again, but it was a different sort of laugh. “I didn’t think I did that so much anymore, nagging you to change the way you live. After knowing you all these years. I’m sorry. You never do that to me.”

“Ah, I do too,” he said. “Getting on you about leaving lights on, not soaking sticky dishes, living on banana-pancake mix half the time. Making fun of the way you scour the whole bathroom whenever you shower—”

“Just the bathtub, come on—”

“Point is, we both do it. That’s how you tell we’re practically in a relationship.” He put an arm around her shoulders. “Look, I tell you what. We go inside—you unpack—I salvage my leftover meatloaf for sandwiches—we maybe take small nap afterward—we work on the porch, or the attic, or the garage, or nothing at all, whatever you like—and tonight we go out to the Skyliner. All Sicilians love the Skyliner Diner.”

“Deal,” she said instantly. “But if I do want to make a start on the garage, that’s what we do. Fair enough?”

“Understood.” But in fact they spent the afternoon peacefully accomplishing nothing of any importance. Joanna dozed, shot desultory baskets into the hoop she had nailed too high on a huge hemlock, threw a pointedly playful fit over a discovered Rosh Hashanah card from Abe’s first wife (“I thought you said she’d found Jesus big-time—what’s she doing sending you High Holidays stuff?”), and sang “Your Cheatin’ Heart” in the bath. Abe hosed raccoon droppings off the stairs that led down to his stony sliver of beach, and loudly searched his sagging bookshelves for a nineteenth-century monograph on fourteenth-century agriculture. (“It was here, it’s always here, I never move it!”) The meatloaf was still edible, the nap sociable; the attic, porch and garage left alone; and four hands of a card game called “That’s All” ended, as usual, in a mild dispute over exactly how many consecutive wins that made for Joanna. Later he washed clothes, while she became entangled in a long, repetitive telephone conversation with Lily that left her depressed, and angry with herself for being so. “Damn her, she pushes buttons I didn’t even know I had—every one, every time. And then she touches my heart, some way, and I say exactly the wrong thing, and I always wind up feeling like such a fool.”

“Well, the buttons work.” He knew better than to say it, and he was unable not to. “If they didn’t work, she’d quit manipulating you the way she does. She’s been doing it to you since she was a child.”

Joanna looked at him for a long time before she spoke again. Her voice was quiet and even, completely unlike her normal tone. “Thank you. I can’t tell you how much I needed to hear that.”

He spread his hands. “Come on, you want the truth or you want comfort? You know I always tell you the truth.”

“Yes,” she said. “You’re the only man who’s ever told me all the truth, all the time. In my life. You’re also the only man I’ve ever wished would lie to me, just now and then. Might show you actually care what I think of you.”

The calm remark caught him amidships, blindside on, and he found himself gasping for words. “I do care, for shit’s sake. Twenty-whatever years, of course I care what you think, you damn well know I care. I just hate to see the same thing happening to you with her, over and over, every time.” He gripped her wrists, and while he could feel her resistance, she did not pull away. “Del, I’m a mean, cranky, solitary old Jew, and I know it, and I like it, and if you didn’t put up with me, who would? You ought to get combat pay.”

“Don’t flatter yourself, you’re not that much trouble. I’ve had cats whose company manners mattered more to me than yours.” But she smiled a little, and moved against him. “See, Lily would notice if I was gone—if I just disappeared—because then she wouldn’t have anyone to yell at, anyone to fail her. You, I sort of wonder. Twenty-whatever years, I don’t know if you’d be anything but inconvenienced.”

He stared at her, amazed to find himself outraged; afraid of spluttering like an aggravated cartoon character if he even opened his mouth. He managed at last to blurt out, “Inconvenienced? Inconvenienced? You really mean that?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I told you, I don’t know.”

It rained that evening—a Gardner Island rain, soft as snow, seeming to blow from all directions, capable of turning to a razor-edged mist within hours—but they drove down to the Skyliner anyway. The diner looked like an old streetcar, sidetracked onto a bare, windy bluff overlooking the Sound. There were no other buildings nearby, and the dark little parking lot was as rutted and potholed as the gravel driveway itself. Even so, the Skyliner was bursting and humming with light, like an acacia tree in spring. They heard music from within, and Abe growled, “Rats, they’ve got the flamenco guy back. I had my face fixed for the trio.”

“Since when don’t you like flamenco?” she asked. “First I’ve heard of it.”

“Since it became music to eat arugula by, that’s when. California cuisine is corrupting everything light beer missed.”

They went in, greeted Corinne, the manager—a dainty retired detective who had always wanted to run a restaurant—and were seated in their usual booth, in back, by a window. The guitarist was flailing doggedly away at a soleares, candles were lit on all the tables, and both Abe and Joanna agreed that the paintings on the walls this month weren’t nearly as horrendous as last month’s exhibit. Abe stole a glass of ice water from a vacant table and let it sit untasted, as he always did. He said, “You look nice.”

“Thank you. You’re cute too, except the beard needs trimming. I wish you’d lose that shirt.”

“Last time, I promise. How’s the bald spot doing?” He bent his head forward for her to inspect.

“You’d have to be looking.” She ruffled his hair, then shook her own head in something more than mock irritation. “Rats, I wish my hair would do that, turn all Spencer Tracy white like yours. Mine’s just going this old-soap gray, just like my mother’s. I think the coloring’s making it worse.”

He touched her hair gently. “Del, I keep telling you, just don’t color it then. United doesn’t care. They’re not allowed to care anymore.”

“The bunnyrabbits care,” she said grimly. “I know it shouldn’t bother me, I know it makes me a bad person, but I’m not going to have them grinning at me, calling me Mom. Lily doesn’t call me Mom, why the hell should they? She’ll probably be calling me Mom too, by the time we get to the salad.”

Abe looked up at the girl standing patiently by their table. “Would you really do that?”

“No,” the girl said. “I would just call her ma’am, and I would say, I’ll be your server tonight. May I tell you about our Special of the Day?”

She was tall, almost as tall as Abe, and slender, and her voice was low and clear, with the slight, warm hint of an accent. Thick and heavy and desert-colored, her hair caught the candlelight and gave it back with the added rawness of a living thing when she turned her head. But her tanned, slightly freckled face—a trifle long by current standards, cheekbones more than a trifle heavy—was at once thoughtful and merry, and her eyes were dark green as elm leaves, and shaped like them, tilting up slightly at the outer corners. She said, “The special is blackened snapper in a ginger-mango sauce, over a jasmine rice pilaf. I really recommend it.”

“Primavera,” Abe said softly. “Primavera, by God.” She looked blankly back at him. Abe said, “Actually by Botticelli. It’s a Renaissance painting of a young girl who represents spring—that’s primavera in Italian. You remind me of her.”

The waitress did not smile, but a shadowy dimple appeared under one cheekbone. “Perhaps she reminds you of me. I can also recommend the pan-seared scallops.”

For more info on SUMMERLONG, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Magdalena Korzeniewska

Design by Elizabeth Story