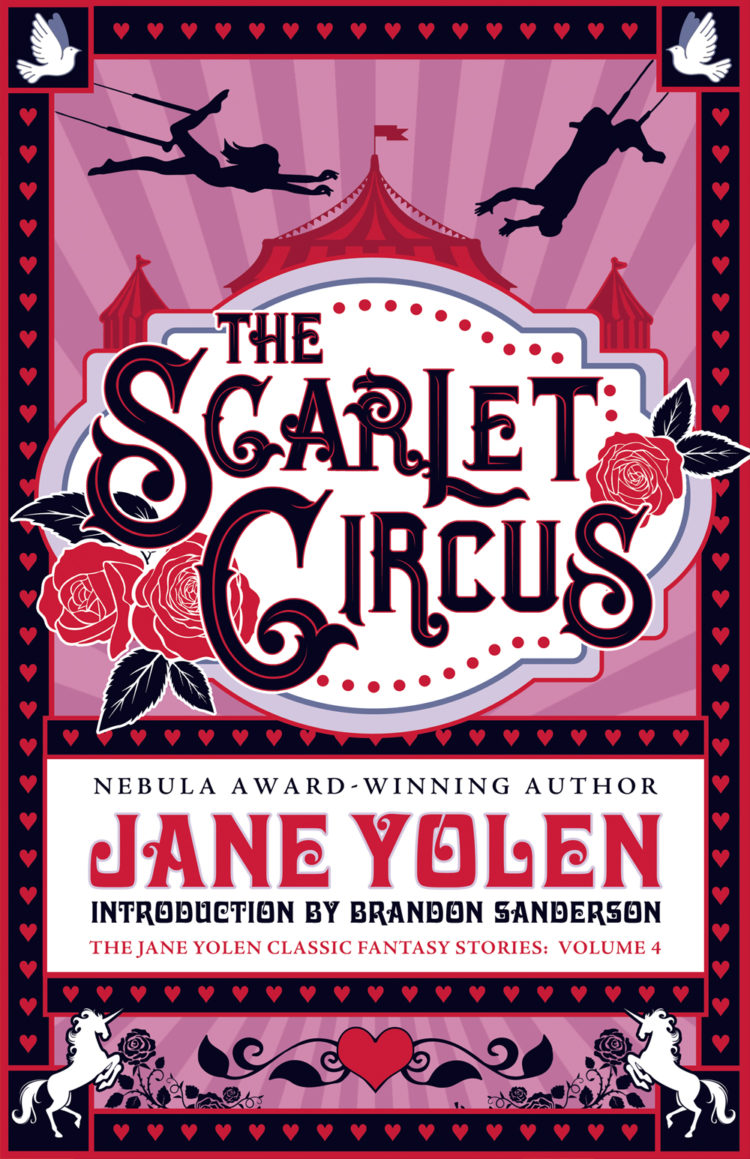

Complete previews from THE SCARLET CIRCUS by Jane Yolen

In celebration of the release of Jane Yolen’s THE SCARLET CIRCUS, Tachyon presents glimpses from the book that “is a magical collection of love stories, where love is often an act of courage and intelligence.” (Anne Bishop, New York Times bestselling author of the Black Jewels series)