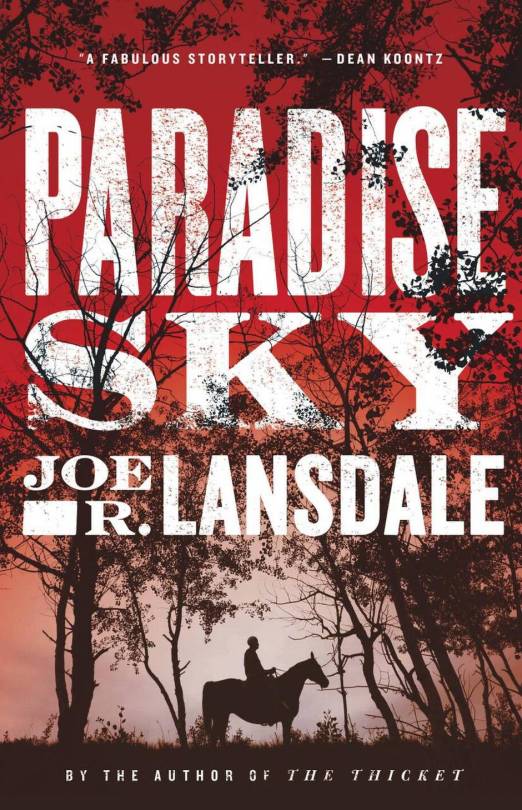

How Joe R. Lansdale found his way to PARADISE SKY

Over at Mulholland Books, Joe R. Lansdale recounts the events that lead him to the black cowboys, THE TRUE LIFE ADVENTURES OF DEADWOOD DICK, and ultimately to his new novel PARADISE SKY.

In the late 1970’s, I became intrigued with nonfiction material I read about black cowboys and soldiers in the Old West. I was surprised to find that their contribution to the West was much larger than I had been led to believe by general history books, Western novels, and films over the years. The reason for this is painful but real: Racism had hidden their contribution. The information was there, and in abundance, but it hadn’t been properly mined. A full quarter or more of the cowboys in the Old West had been black or of color. You didn’t see this in Westerns. Blacks were always maids and cooks in novels and film, if they were represented at all.

Most of the material about their lives and times in the West, was nonfiction. John Ford had touched on it in a safe way in his film Sergeant Rutledge. Still, on the posters the main star was Jeffery Hunter, not the black actor, Woody Strode, who played the title character. There were a few novels about blacks in the West, but I didn’t encounter any that were epic. I was thinking of writing one in the vein of Wild Times by Brian Garfield, Little Big Man by Thomas Berger, The Big Sky by A.B. Guthrie, Jr., or The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters by Robert Lewis Taylor. I wanted to write about the real black experience in the West, and at the same time, make it larger than life. I had also read an autobiography about Western life by a black cowboy named Nat Love. Nat Love’s experiences were no doubt influenced by the dime novels of his era, so it has to be taken with a grain of salt, but his story was epic, and it was clear he knew his business when it came to being a cowboy. He knew the world of his time, and was able to express it in such a way as to put you there. It was the kind of book I wanted to write. Better yet, it was a book by an actual black cowboy. He was doing the same thing that many white Westerners had done. He was “stretching the blanket,” as they used to say, taking kernels of truth and turning them into a kind of hybrid product that housed both reality and dadburn lies. He claimed to have acquired the nickname Deadwood Dick due to a shooting match he won in old Deadwood, and he also claimed the dime novels about Deadwood Dick, the Black Rider of the Plains, were based on him. No doubt they were not, but this was a kind of wish fulfillment for Nat, so he took his life and welded it to the Wild West tale. Unlike so many dime novel heroes, Nat’s adventures seemed real.

Read the rest of Lansdale’s fascinating essay at Mulholland Books.