THE MADONNA AND THE STARSHIP was originally titled THAT BUCK ROGERS STUFF & other revelations

Over at SF Signal, Andrea Johnson talks to the mutliple award-winning author James Morrow about his new book The Madonna and the Starship and other revelations.

Could it be that science fiction, even in its pulpiest forms, helps us get our bearings as we maneuver between the extremes of logical positivism and truculent theism? I think so. For many generations, the default sensibility of the genre was atheist — but it was never merely atheist. The foundational SF texts spontaneously melded their materialism with awestruck visions of the cosmos. For the plot to work, The Madonna and The Starship had to be set in the early 1950′s, the era of live television. But the engagement with metaphysical questions was characteristic of science fiction from the very beginning.

The Madonna and The Starship was originally titled That Buck Rogers Stuff. My plan was to transport the cast of a children’s TV space opera to a planet (or perhaps a future) where a war of the worldviews—logical positivism versus scorched-earth theism—was threatening to tear the dominant civilization apart. Back on Earth, of course, the philosophical mindset embodied by science fiction is being routinely dismissed as “that Buck Rogers stuff.” Against the odds, my dauntless troupe of actors would have found itself in a position to negotiate a truce between the two Weltanschauungs. But this was supposed to be a novella, not an epic, so I decided to simplify things by keeping the actors on Earth.

<snip>

One thing I believe I got right in The Madonna and The Starship is the ambience and protocols of a pre-digital TV studio. In 1973, after getting a teaching degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, I went to work for the Chelmsford Public Schools in Massachusetts. Sometime in the 1960’s, not too long after the invention of videotape, the Chelmsford administrators had undertaken to wire the entire system for closed-circuit television, with an elaborate studio at the nexus (located in one of the middle schools). This curious and ostensibly enlightened institution was actually rather regressive in intent. The administrators thought that by embalming the “minor” subjects on videotape – art, shop, home economics, music appreciation – they could ultimately fire the corresponding teachers. I don’t think the scheme worked out very well. There is no substitute for a flesh-and-blood instructor. But the students eventually commandeered the facilities for their own purposes.

As the Chelmsford school system’s graphic artist and media specialist, I often found myself in the central TV studio, helping the students broadcast a daily morning show, create instructional videos for their English and Social Studies classes, and produce original dramas and comedies for the sheer delight of it. Although most of these program were recorded on tape, they all employed the grammar of live television—switching from camera 1 to camera 2 to camera 3 in real-time without interruption—and the stuff I learned during those years informs the climax of The Madonna and The Starship.

For the rest of this fascinating interview which includes discussions about teaching Tolkien to 7th graders, a Darwin epic, and Morrow’s 8MM film efforts, visit SF Signal.

For more on The Madonna and the Starship, visit the Tachyon page.

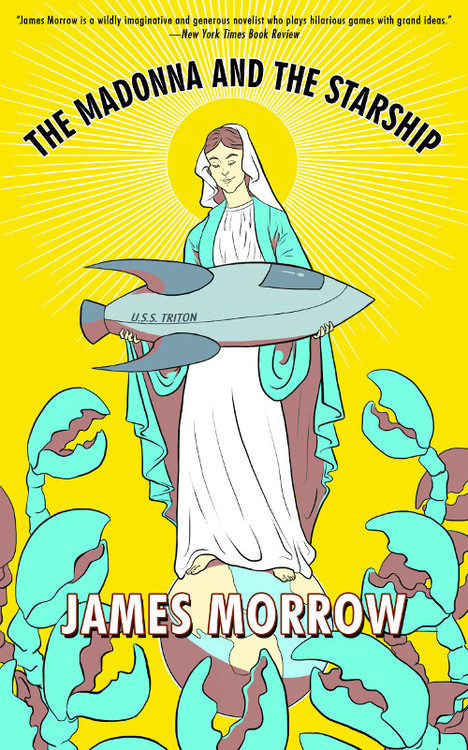

Cover and design by Elizabeth Story