Why humanity may yet reach the stars

(Photo by SFX Magazine/Getty Images)

At REUTERS, Alastair Reynolds, author of SLOW BULLETS, discusses the realities of interstellar travel.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but it’s starting to look as if Einstein might just have been right about that speed of light thing. From apparently superluminal radio sources in deep space, to the neutrinos that were supposed to be arriving ahead of schedule at the Grand Sasso experiment in Italy, every apparent exception to Einstein’s ultimate speed law has turned out to be a phantom. Even in the quantum realm, where entangled particles seem to communicate with each other instantaneously across any distance, no useful information is shared at anything other than the speed of light.

But that doesn’t mean that interstellar travel is itself a fantasy. Travel below the speed of light — but as arbitrarily close to it as you wish — is perfectly feasible. Of course, that isn’t the same thing as saying it will be easy. Imagining the technologies that will carry us to the stars places us in roughly the same position as Leonard da Vinci, when he first sketched the concept behind the helicopter. Getting close to the speed of light will demand energies and materials beyond anything within our current capabilities. Chemical rockets certainly won’t cut it, nor the ion propulsion systems employed by some spacecraft. Even dauntingly difficult fusion power wouldn’t be up to the job. But perhaps harnessing antimatter, or the power of miniature black holes, may just give us the tools. At the moment we can make antimatter in tiny quantities, but not nearly enough to fuel a ship. And while we suspect that miniature black holes may exist, and may even be produced in high-energy physics experiments like the Large Hadron Collider, so far they’ve proven elusive.

(Photo by REUTERS/Scott Audette)

Be careful what you wish for, though, because an increase in our knowledge of other solar systems could have exactly the opposite effect — dampening our enthusiasm, not stoking it. Such worlds may not be as enticing as we now imagine. While it would be nice to find life-bearing planets, gorgeous blue-green marbles with oceans and vegetation, they may be vanishingly rare. Perhaps the majority of worlds will fall into a handful of similar categories, with very few surprises — rocks, gas giants, hot Jupiters — endless reiterations of the same few themes. While this data will vastly enrich our knowledge of the surrounding cosmos, it may have a chilling effect on our aspirations. After all, why cross light years to end up at a place much the same as the one you left? It could even be one explanation of the Fermi paradox, the puzzling absence of interstellar travelers in our own vicinity. Perhaps alien civilizations learn enough about their place in the galaxy that they lose the imperative to engage in physical exploration and colonization.

Read the rest of Reynolds’ fascinating essay at REUTERS.

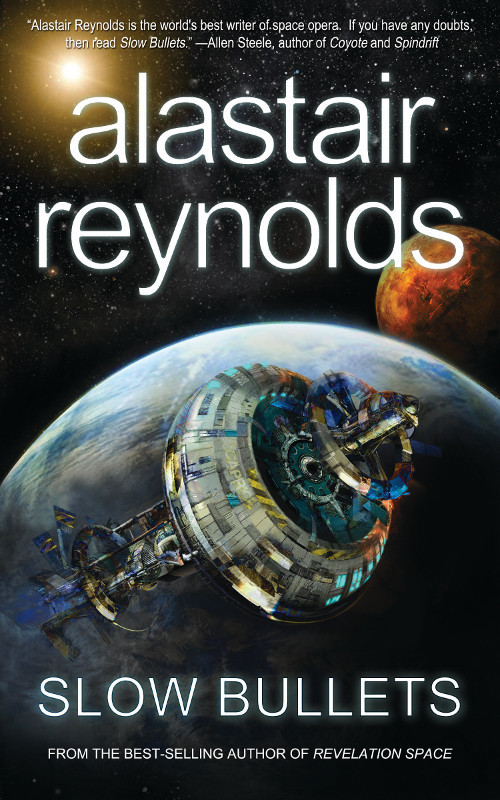

For more about SLOW BULLETS, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover art by Thomas Canty.

Design by Elizabeth Story.