The classic science fiction behind Lavie Tidhar’s CENTRAL STATION

Over at TOR.COM, Lavie Tidhar lists the Five Classic Science Fiction Stories That Helped Shape CENTRAL STATION.

CENTRAL STATION, my new SF novel from Tachyon Publications, is itself a sort of homage to a bygone era of science fiction, one in which many novels were initially published as more or less self-contained stories in magazines before being “collected” into a book. Appropriately, CENTRAL STATION corresponds with many other works of the corpus of science fiction, though perhaps not always the obvious ones. Here are five novels that helped shape my own work.

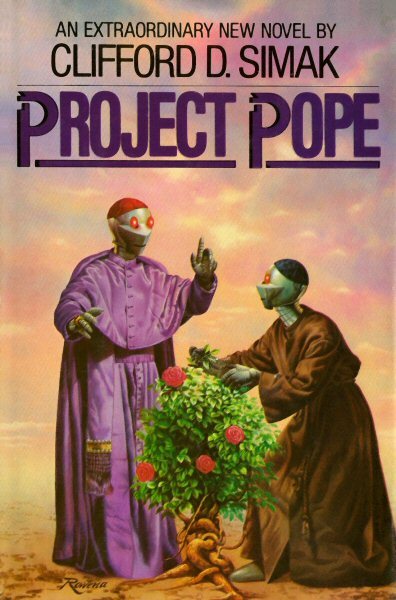

PROJECT POPE, Clifford Simak (1981)

Simak’s been a surprisingly large influence on me. He is far less known today than he was, I think—a rare proponent of “pastoral SF” which resonates with me, I think, partially because of my own upbringing on a remote kibbutz. His best known novel, CITY, was itself a mosaic or (a somewhat controversial term, it seems) a “fix-up” of short stories, which was one of the obvious inspirations for CENTRAL STATION.

PROJECT POPE, however, concerns itself with a society of robots on a remote planet who have established their own Vatican in search of God. It’s a minor Simak, but it’s directly influenced my own order of world-weary robots, who dream of children of their own, follow the Way of Robots, act as sort of neighbourhood priests, and go on pilgrimage (the ‘robot hajj’) to their own Vatican in Tong Yun City on Mars… in CENTRAL STATION, the local robot, R. Brother Fix-It, doubles up as the moyel for the Jewish community—I don’t think Simak ever wrote a circumcision scene!

It’s an odd book, the sort of science fiction I loved growing up but which seems to increasingly vanish into the past with the demands of more commercial story telling.

Check out the rest of Tidhar’s selections at TOR.COM.

Photo: Kevin Nixon. © Future Publishing 2013.

Simon Yaffe interviews Tidhar for the JEWISH TELEGRAPH.

“We can assume that the Israelis and the Palestinians are part of a federated state,” Lavie said of the book. “At some point, the Palestinians’ right of return

was activated and they co-exist with the Israelis.“Jaffa is Arab, Tel Aviv is Jewish and the central station acts as a buffer zone between them.

“Funnily enough, before Central Station came out, I read a piece in an Israeli newspaper that a political organisation wastrying to push for that solution.

“I guess it is life imitating fiction — or the other way round!”

<snip>

And it was while walking past Tel Aviv’s Central Station that he had the idea for the book.

The 39-year-old recalled: “As an area, I found it interesting. Much of it had been settled by African refugees on one side and Asian economic migrants on the other.

“It is the sort of place that Israelis do not like to go near. “I thought about how the area could look in a far-future setting and to follow the lives of our great-great-great-great grandchildren.”

At +972 Beth Kissileff talks with Shimon Adaf and Lavie Tidhar, authors of ART AND WAR.

Have you ever eavesdropped on the conversations of the brilliant people at the table next to you, and wanted to jump in and interrupt, to ask your own questions?

ART

AND WAR: POETRY, PULP AND POLITICS IN ISRAELI FICTION, a new book of conversations between two writers, is sure to make readers feel that way.ART AND WAR consists of conversations between Sapir Prize winning Tel Aviv resident Shimon Adaf and World Fantasy Award winning London resident Lavie Tidhar about the many things that enlighten, bother, and frighten them. They talk here about their worries about the book’s coming out, the realities of Israel today, the Holocaust, science fiction, digression, and how to answer for fictional characters – or each other. Being writers, they’ve each written a story at the conclusion of the dialogue in which the other is a character. Art and Warcomes from that impulse good friends have to push their friend and force them to actually make sense and clarify statements. Or, in the words of the authors via email, it is, “very much a conversation, not an agreement. Think of two cranky old rabbis having an argument about the right way to boil an egg and that, I suspect, would be closer to it!” says Lavie Tidhar. Shimon Adaf characterizes their interchanges as like “two Halacha students shouting over the status of an egg that has been laid during a holiday…”

BK: Lavie writes, “I see literature as an act of unbalancing, as a challenge. It needs to upset people, it needs to push. It needs, I think, to be uncomfortable. It shouldn’t please.” How is this done? Are there limits?

Shimon: I think it is more a regulative idea than a concrete goal. It means that writers should start by working out the conventions and systems of values of their time (and of the literature written in order to ascertain them) and find a way to expose them or oppose them. It means that writing, basically, should be a critical act. And as for limits, is it a question about the limits of oppositions and provocation or about the writers’ limits of thinking outside of the paradigms of their time? If it’s the first, it is up to each writer to decide for themselves. If it’s the second, then of course there are limits. It’s hard to admit, but writers are human too.

Lavie: Graham Greene made a distinction between his ‘novels’ and his ‘entertainments,’ but later on his life had to admit it was a pointless distinction. I think the position I come from is you try to write the entertainment, and kind of hide the rest inside it. I think it’s why I’ve been attracted early on to science fiction – it can be a very subversive literature that masquerades as cheap entertainment. You can see it used that way in repressive regimes – the Soviet Union is often given as an example.

Check out the rest of the fascinating interview at +972.

For more info about CENTRAL STATION, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Sarah Anne Langton