Subtle CENTRAL STATION is wildly inventive

For THE ANGLIA RUSKIN CENTRE FOR SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY, Victoria Hoyle praises Lavie Tidhar’s bold CENTRAL STATION.

I entered into CENTRAL STATION with few expectations. It was my first encounter with Tidhar’s work, either in short or long form; and I knew next to nothing about the book’s premise or evolution. As I mentioned in my shortlisting post, I chose it as one of my six almost entirely based on reputation and the opening pages of the Prologue. Which, it turns out, are not bad selection criteria. Tidhar’s novel is both subtle and quotidian, bolshie and wildly inventive. In common with some of its characters, it is a cyborg patchwork; a novel about a bold future that has its feet firmly planted in the past.

The book started life as a series of short stories, reworked and ordered here within a narrative frame to form a novel. It’s complex and wily, structured around three points in time: a present, a future and a far future. The author introduces themselves quietly in a first-person Prologue, a writer sitting down in a shebeen in Tel-Aviv – perhaps in our present, perhaps not – to tell a science fiction story. They sip cheap beer while the rain falls outside and put pen to paper: ‘Once the world was young,’ they begin, ‘The Exodus ships had only begun to leave the solar system then…’ (2) Our writer in the present addresses us as if were a knowing audience in a far distant future, ‘sojourners’ amongst the stars who tell ‘old stories across the aeons.’ These stories – of ‘our’ past but the author’s fictional future – make up the meat and substance of the book that follows. It sounds like rather a baroque set-up and it’s barely gestured at but it is thematically fundamental. CENTRAL STATION is a book about how the future remembers, about the future’s past. It’s a historical novel as much as a science fiction novel.

<snip>

If there was one thing I didn’t expect from this novel, it was all the love: romantic love, familial love, the love between friends. That, and the joy. Tidhar has an admirable gift for writing tenderness and affection without cliché. The prose is sensory and sensuous; we are forever being reminded how things smell, taste, sound and feel. The book is full of weather. It’s a quiet carnival of feelings, expressed through the exuberance of commas, conjunctives, the breathless ‘and’ and ‘and’ and ‘and’ of the novel’s style. The book’s romantic pairings – Miriam and Boris, Motl and Isobel, Achimwene and Carmel – are its load-bearing structure, while the family relationships – between Boris and his father Vlad, between Miriam and Kranki, Ibrahim and Ismail – are its four solid walls. Memory is the stuff that cements it all together, although it’s not an unequivocal good. Boris’s grandfather Weiwei Zhong was so determined to be remembered that he made a deal with the Others that means Boris and his father Vlad, as well as all of their relatives and descendents, share a familial memory. They can recall things that have happened to one another with cinematic accuracy. While it brings them close together, luring Boris back to Central Station in spite of his attempts to escape, it’s also their curse. Vlad is suffering from a kind of dementia, in which his many thousands of memories are fragmenting, losing coherence and emerging at random. It’s a surfeit of remembering that leaves him unmoored and battling to recapture what makes him Vlad; while he loses some of the things that are important to him – his wife’s name – he is burdened with the arcane memories of his ancestors. It’s a powerful metaphor for how the past, and our memory of it, is both a tool and a weapon. It can’t be a mistake that CENTRAL STATION is set in Tel Aviv, a city founded on a utopian vision of strategic remembering and forgetting that told one story at the loss of many others. We use and misuse the past to justify our choices, and shut out the parts we’d rather not own.

I return to the love though, and how this book left me with a giddy feeling of possibility. It ends on a note that suggests a powerful belief in hope, in joy even in death. However the past marks us, however the future will change us, Tidhar imagines continuity amidst the wrenching disjuncture. In the shadow of a space station ‘laundry [is] hanging as it had for hundreds of years’ (55), and from the far distant future of the Prologue we are still telling stories about it. For me this is the kind of story that people were yearning for in Becky Chamber’s A LONG WAY TO A

SMALL ANGRY PLANET but with all the nuance and poetry that book lacked. Like that story this one is episodic, sometimes repetitive (a function, no doubt, of the stories being published separately in other venues), diverse, transgressive; unlike that story it’s original, tightly structured, rigorously imagined. The book extends outwards too. CENTRAL STATION is little more than a taste of what this imagined world is capable of and you can tell, from the cheeky character list at the end of the book, that Tidhar has more, infinitely more, stories about it in him.

Hoyle shares additional thoughts on YOU TUBE.

At JEWISH STANDARD, Larry Yudelson enjoys the book.

This ghostly perfume is a poetic conceit that defines the difference between CENTRAL STATION and the 20th century classics of science fiction it alludes to, pays tribute to, and in many ways improves upon.

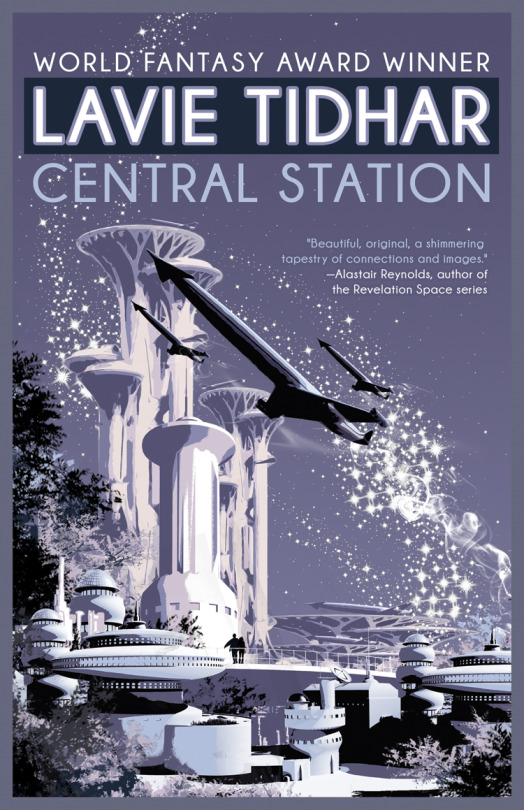

CENTRAL STATION is the translation of Hatachana Hamercazit, the central bus station in Tel Aviv that, in Lavie Tidhar’s imagination, has grown into a towering spaceport over the centuries. No doubt this image reflects how Tidhar saw the skyscrapers of Tel Aviv and the urban bustle of its bus station when he was growing up on a rural kibbutz in northern Israel, reading translated American science fiction.

<snip>

CENTRAL STATION asserts that in the science fictional present, in the realm of what once was called future shock, people live the way people have always lived: with the mixture of love, longing, and loss that is unique for every person (or robot) yet is ultimately universal. The present looks different from the past and the future promises even more change, but the human feelings underneath remain the same. Young lovers, old flames reunited after decades, parents with children they love for all their incomprehensible differences, the forgotten veterans suffering from the last war or the war before that — and yes, the fondly recalled memory of the orange groves of long ago.

Unlike much science fiction, CENTRAL STATION is not propelled by plot. In part that may be an accident of its history; it began as a series of related short stories. But the medium is the message. As in Clifford Simak’s City cycle, the setting and characterization common to the stories are more important than the arcs of drama that last for only a chapter or two.

<snip>

And there is the ghostly scent of the orange groves. Because amidst the loves and the fears, Tidhar reminds us of the intoxicating and invigorating power of longing and nostalgia, even nostalgia for a vanished future.

For more info about CENTRAL STATION, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover and image by Sarah Anne Langton