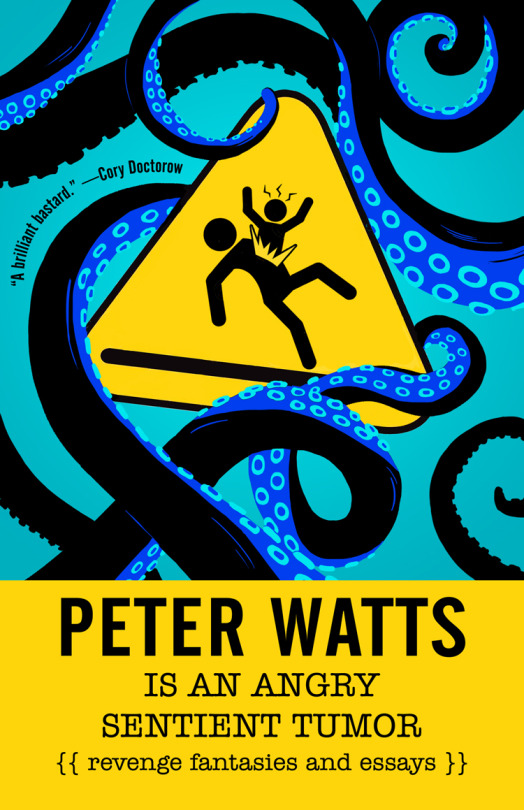

PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR preview: “Life in the FAST Lane”

In celebration for the release of the irreverent, self-depreciating, profane, and funny PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, Tachyon presents glimpses from the essay collection.

Life in the FAST Lane

by

Peter Watts

Back in 2007 I wrote a story about a guy standing in line at an airport. Not much actually happened; he just shuffled along with everyone else, reflecting on the security check awaiting him (and his fellow passengers) prior to boarding. Eventually he reached the head of the queue, passed through the scanner, and continued on his way. That was pretty much it.

Except the scanner wasn’t an X-ray or a metal detector: it was a mind-reader that detected nefarious intent. The protagonist was a latent pedophile whose urges showed up bright and clear on the machine, even though he had never acted on them. “The Eyes of God” asks whether you are better defined by the acts you commit or those you merely contemplate; it explores the obvious privacy issues of a society in which the state can read minds. The technology it describes is inspired by a real patent filed by Sony a few years ago; even so, I thought we’d have at least couple more decades to come to grips with such questions.

I certainly didn’t think they’d be developing a similar system by 2015.

Yet here we are: a technology which, while not yet ready for prime time, is sufficiently far along for the American University Law Review to publish a paper1 exploring its legal implications. FAST (Future Attribute Screening Technology) is a system “currently designed for deployment at airports” which “can read

minds … employ[ing] a variety of sensor suites to scan a person’s

vital signs, and based on those readings, to determine whether the

scanned person has ‘malintent’—the intent to commit a crime.”

The envisioned system doesn’t actually read minds so much

as make inferences about them, based on physiological and

behavioral cues. It reads heart rate and skin temperature, tracks

breathing and eye motion and changes in your voice. If you’re

a woman, it sniffs out where you are in your ovulation cycle. It

sees your unborn child and your heart condition—and once it’s

looked through you along a hundred axes, it decides whether you

have a guilty mind. If it thinks you do, you end up in the little

white room for enhanced interrogation.

Of course, feelings of guilt don’t necessarily mean you plan

on committing a terrorist act. Maybe you’re only cheating on

your spouse; maybe you feel bad about stealing a box of paper

clips from work. Maybe you’re not feeling guilty at all; maybe

you’re just idly fantasizing about breaking the fucking kneecaps

of those arrogant Customs bastards who get off on making every

one’s life miserable. Maybe you just have a touch of Asperger’s,

or are a bit breathless from running to catch your flight—but all

FAST sees is elevated breathing and a suspicious refusal to make

eye contact.

Guilty minds, angry minds, fantasizing minds: the body betrays

them all in similar ways, and once that flag goes up you’re a Person

of Interest. Most of the AULR article explores the Constitutional

ramifications of this technology in the US, scenarios in which

FAST would pass legal muster and those in which it would violate

the 4th Amendment—and while that’s what you’d expect in a legal

commentary, I find such concerns almost irrelevant. If our rulers

want to deploy the tech, they will. If deployment would be illegal

they’ll either change the law or break it, whichever’s most convenient. The question is not whether the technology will be deployed.

The question is how badly it will fuck us up once it has been.

Let’s talk about failure rates.

If someone tells you that a test with a 99% accuracy rate has

flagged someone as a terrorist, what are the odds that the test is

wrong? You might say 1%; after all, the system’s 99% accurate,

right? The problem is, probabilities compound with sample size—

so in an airport like San Francisco’s (which handles 45 million

people a year), a 99% accuracy rate means that over 1,200 people

will be flagged as potential terrorists every day, even if no actual

terrorists pass through the facility. It means that even if a different

terrorist actually does try to sneak through that one airport every

day, the odds of someone being innocent even though they’ve

been flagged are—wait for it—over 99%.

The latest numbers we have on FAST’s accuracy gave it a score

of 78–80%, and those (unverified) estimates came from the same

guys who were actually building the system—a system, need I

remind you, designed to collect intimate and comprehensive

physiological data from millions of people on a daily basis.

The good news is, the most egregious abuses might be limited

to people crossing into the US. In my experience, border guards in

every one of the twenty-odd countries I’ve visited are much nicer

than they are in ’Murrica, and this isn’t just my own irascible bias:

according to an independent survey commissioned by the travel

industry on border-crossing experiences, US border guards are the

world’s biggest assholes by a 2-to-1 margin.

Which is why I wonder if, in North America at least, FAST

might actually be a good thing—or at least, a better thing than

what’s currently in place. FAST may be imperfect, but presumably

it’s not explicitly programmed to flag you just because you have

dark skin. It won’t decide to shit on you because it’s in a bad mood,

or because it thinks you look like a liberal. It may be paranoid and

it may be mostly wrong, but at least it’ll be paranoid and wrong

about everyone equally.

Certainly FAST might still embody a kind of emergent

prejudice. Poor people might be especially nervous about flying

simply because they don’t do it very often, for example; FAST

might tag their sweaty palms as suspicious, while allowing

the rich sociopaths to sail through unmolested into Business

Class. Voila: instant class discrimination. If it incorporates face

recognition, it may well manifest the All Blacks Look Alike To

Me bias notorious in such tech. But such artifacts can be weeded

out, if you’re willing to put in the effort. (Stop training your face-

recognition tech on pictures from your pasty-white Silicon Valley

high school yearbook, for starters.) I suspect the effort required

would be significantly less than that required to purge a human

of the same bigotry.

Indeed, given the prejudice and stupidity on such prominent

display from so many so-called authority figures, outsourcing at

least some of their decisions seems like a no-brainer. Don’t let

them choose who to pick on, let the machine make that call; it

may be inaccurate, but at least it’s unbiased.

Given how bad things already are over here, maybe even some-

thing as imperfect as FAST would be a step in the right direction.

1/ Rogers, C.A. 2014. “A Slow March Towards Thought Crime: How The

Department Of Homeland Security’s Fast Program Violates The Fourth

Amendment.” American University Law Review 64:337–384.

For more info about PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover design by Elizabeth Story

Icon by John Coulthart