THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “The Pied Piper of Hammersmith” by Nicholas Royle

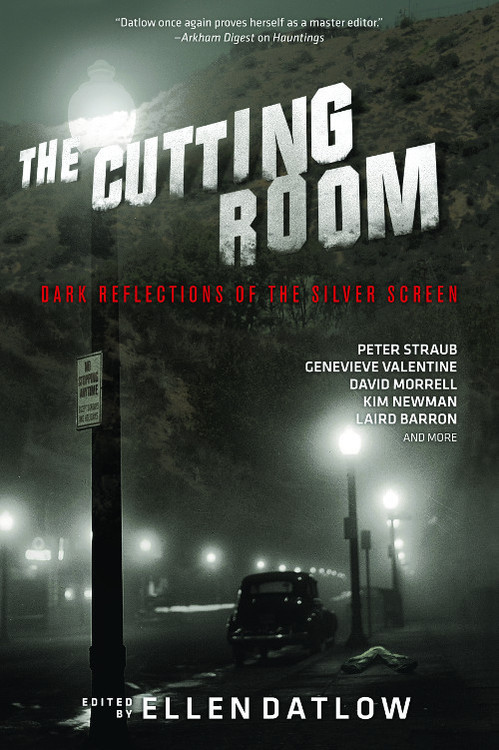

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “The Pied Piper of Hammersmith” by Nicholas Royle.

If you’ve ever sat alone at night in one of those houses or flats that back on to the overground sections of the Hammersmith & City line, then you will know—as Michael did—that the trains that go by, with images and light shining out of oblong frames, are not trains at all, but movies.

After the many hours he spent as a child watching them day after day, night after night, year after year, Michael knew he was destined for a life in movies. But it didn’t work out the way he might have planned it.

Michael had never set eyes on his mother, a first-reel casualty. His father lived in a world of his own, its dimensions those of his house in Shepherd’s Bush. Michael rented a Hammersmith bedsit. Uncomfortably close to his father, it’s true, but the old man could have had no idea—or even care—that Michael was even still alive, never mind living under a mile away.

Michael worked for one of the big production companies. In Dispatch. In a Great Titchfield Street basement, cans of film stacked up high on the shelves. Videocassette Canary Wharves—U-matic, Betacam, VHS. Michael signed them in and signed them out. A life in movies. The only time he ever saw a piece of film was if a dispatch rider dropped a can and the lid fell off.

“What’s all this about shift work?” his manager asked him.

“Movie commitments,” Michael replied, quick as a flash. “Film work.”

The guy gave him a funny look, but it was true enough and it got Michael the late shifts he was after. All so that when he went home on the overground sections of the Hammersmith & City line, it was nighttime on the other side of the screen.

“Now it’s dark,” Michael muttered in deliberate echo of Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth every time he boarded at Great Portland Street. “Now it’s dark.”

Darkness was the first prerequisite for film projection. Just as matinée shows weren’t proper screenings, so too the trains that ran during daylight were not real movies. The Hammersmith & City line was genuine cinema. They may have only been short films, curtain-raisers, appetite-whetters, but Michael gave it all he had. Every ride home in the dark was a fresh performance, another stab at the part.

He hadn’t satisfied himself that he knew where these films came from or who made them or why they were different from the ones on his shelves at work or indeed, in video format, on his shelves at home. But he took them seriously—as seriously as if the Oscar were up for grabs every night of the week.

As the carriages trundled between Great Portland Street and Baker Street, this was the leader edge of the first reel, black celluloid, no images to project. Sometimes the film would get stuck in the gate of the projector between Baker Street and Edgware Road. The actor-passengers around Michael would cluck with impatience, improvising frenetically as they watch-checked, mobile-phoned.

Michael remained calm. Sooner or later the driver-projectionist would right the film and, once they were out of Edgware Road, the movie proper began. An illuminated strip of celluloid shooting out into the night, its audience the rear mansion flats of Gloucester Terrace, the boxy council apartments of Westbourne Park, the Edwardian owner-occupieds of Shepherd’s Bush—one of them Michael’s father’s place, the portion of the audience Michael kept especially in mind as he worked on his performance night after night. Just as day after pitiless day, Michael had lain in his cot watching, from behind its bars, as the trains went by. Twenty-four hours a day—his father working obsessively on his own doomed projects, his painstaking documentaries of animal life and reproductive cycles.

Michael’s room was at the back of the house. He lay in his cot and he sat in his pram and watched the trains. Lucky if he got fed once a day. He cried and yelled and watched the trains through his tears.

Michael had noticed the blind people at Great Portland Street. Who hadn’t—apart from the blind people themselves? The station saw a lot of white-stick merchants passing through its gates, their reactions to normal acts of kindness—offers of assistance out of the station, across the road—ranging from genuine pleasure to unmasked irritation. Michael liked to help. Liked being thanked, disliked having charity thrown back in his face.

In Dispatch, Michael was ticking off the days. A can of film had sat on the bottom shelf, the bottom shelf at the back, for just under six months, having appeared one day before the start of his shift and never been picked up. Never even appeared on the worksheet.

He gave himself six months. Long enough for a mistake to be rectified. If no one came to pick up the can in six months, not only did Michael feel he could legitimately sneak it home himself, but he could assume it had been put there for him—and he had passed some kind of test by not taking it before.

He hadn’t even opened the can. It could be empty. But something told him it wasn’t. He didn’t even need to check—as long as he left it undisturbed for six months it would turn out to contain film for his eyes only.

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.