THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “Bright Lights, Big Zombie” by Douglas E. Winter

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “Bright Lights, Big Zombie” by Douglas E. Winter.

“When I started using dynamite, I believed in many things… .

Finally, I believe only in dynamite.”

—Sergio Leone, Giu la testa

IT’S 6 A.M.

DO YOU KNOW

WHERE YOUR BRAINS ARE?

You are not the kind of zombie who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. You are not a zombie at all: not yet. But here you are, and you cannot say that the videotape is entirely unfamiliar, although it is a copy of a copy and the details are fuzzy. You are at an after-hours club near SoHo, watching a frantic young gentleman named Bob as the grooved and swiftly spinning point of a power drill chews its way through the left side of his skull. The film is known alternatively as City of the Living Dead and The Gates of Hell, and you’re not certain whether this version is missing anything or not. All might come clear if you could actually hear the soundtrack. Then again, it might not. The one the other night was in Swedish or Danish or Dutch, and a small voice inside you insists that this epidemic lack of clarity is a result of too much of this stuff already. The night has turned on that imperceptible pivot where 2 a.m. changes to 6 a.m. Somewhere back there you could have cut your losses, but you rode past that moment on a comet trail of bullet-blown heads and gobbled intestines, and now you are trying to hang onto the rush. Your brain at this moment is somewhere else, spread in grey-smeared stains on the pavement or coughed up in bright patterns against a concrete wall. There is a hole at the top of your skull wider than the path that could be corkscrewed by a power drill, and it hungers to be filled. It needs to be fed. It needs more blood.

THE DEPARTMENT

OF VICTUAL

FALSIFICATION

Morning arrives on schedule. You sleepwalk through the subway stations from Canal Street to Union Square, then switch to the Number 6 Local on the Lexington Avenue Line. You come up from the Thirty-third Street Exit, blinking. Waiting for a light at Thirty-second, you scope the headline of the Daily News: still dead. There is a blurred photograph of something that looks vaguely like a hospital room. You think about those four unmoving bodies, locked somewhere inside the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. You think about your mother. You think about Miranda. But the light has changed. You’re late for work again, and you’ve worn out the line about the delays at the checkpoints. There is no time for new lies.

Your boss, Tony Kettle, runs the Department of Victual Falsification like a pocket calculator, and lately your twos and twos have not added up to fours. If Kettledrum had his way, you would have been subtracted from the staff long ago, but the magazine has been shorthanded since Black Wednesday, and sooner or later you manage to get your work done. And let’s face it, you know splatter films better than almost anyone left alive.

The offices of the magazine cover a single floor. Once there were several journals published here, from sci-fi to soft porn to professional wrestling. Now there is only the magazine, a subtenant called Engel Enterprises, and quiet desperation. You navigate the water-stained carpet to the Department of Victual Falsification. Directly across the hall is Tony’s office, and you stagger past with the hope that he’s not there.

“Good morning, gorehounds,” you say as you enter the department. There are six desks, but only three of them are occupied. Brooks is reading the back of his cigarette package: Camel Lights. Elaine shakes her head and puts her blue pencil through line after line of typescript. Stan, who has been bowdlerizing an old Jess Franco retrospective for weeks, shuffles a stack of stills and whistles an Oingo Boingo tune. J. Peter and Olivia are dead.

What once was your desk is now a prop stand for a mad maze of paper. An autographed photo of David Warbeck is pinned to the wall and looks out over old issues of Film Comment, Video Watchdog, Ecco, Eyeball, the Daily News. Here are the curled and coffee-stained manuscripts, and there the rows of reference volumes, from Grey’s Anatomy to Hardy’s Encyclopedia of Horror Film. Somewhere in the shuffle are two lonely pages of printout, the copy you managed to eke out yesterday from the press kit for John Woo’s latest bullet ballet, smuggled through Customs between the pages of a Bible.

Atop it all is a pink message slip with today’s date: Ruggero Deodato called. Don’t forget about tonight. “And hey,” Brooks says, finally lighting up a cigarette. “We had another visit from the Brain Police.” You are given a look that is meant to be serious and significant.

You have spent the last five years of your life presenting images of horror, full color and in close-up, to a readership—perhaps you should say viewership—of what you suspected were mostly lonely, adolescent, and alienated males who loved these kinds of films. The bloodier the better. Special effects—the tearing of latex flesh, the splash of stage crimson, the eating of rubber entrails—were the magazine’s focus, and in better days, after a particularly vivid drunk that followed a screening of the latest Night of the Living Dead rip-off, you and J. Peter and Tony came to call yourself the Department of Victual Falsification.

That was then, and this is now. The dead came back, not for a night but for forever. Your mother. Black Wednesday. Miranda. Cannibals in the streets. The bonfires in Union Square. Law and order. Congressional hearings. Peace, complete with special ID cards and checkpoints and military censors.

You remember, just before the Gulf War, reading newspaper articles about high school students who paged through magazines that were to be sent to the troops in Saudi Arabia, coloring over bras and bare chests, skirts that were too short, cigarettes caught up in dangling hands. You thought that this was supremely funny. Now each month you do something much the same. The magazine publishes the latest additions to the lists, recounts the seizures from the shelves of the warehouses and rental stores. At first the banished titles were the inevitable ones, the old Xs and the newer NC-17s and, of course, anything to do with the living dead. In recent months, the lists have expanded into the Rs and a few of the PG-13s.

You are detectives of the dying commodity called horror, and there are fewer places where the magazine is sold, and fewer things that you can say, and fewer photos for you to run and, of course, there are fewer people left alive, fewer still who care.

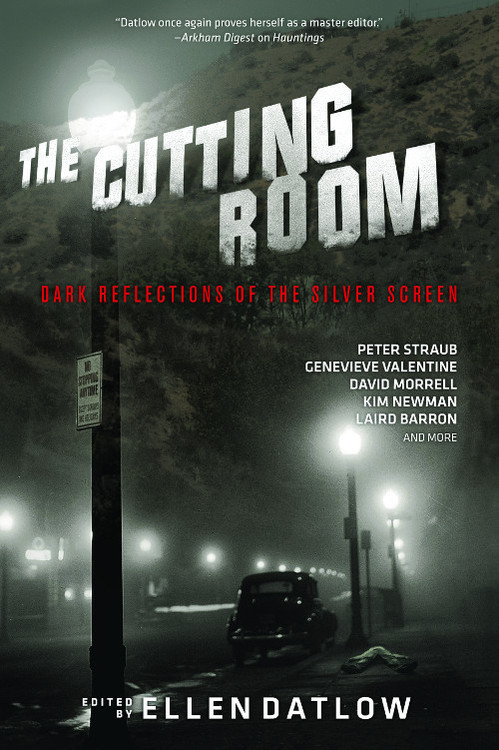

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.