THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “Cinder Images” by Gary McMahon

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “Cinder Images” by Gary McMahon.

Fade in. Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony Number 6, slow and sweet. No title bar or opening credits.

It starts with a little girl, running.

She is young—perhaps eight or nine years old—and she is pumping her arms and her legs as she runs along a dirt road. Behind her, fire burns a line along the horizon. Around her, there is scorched and blackened earth and the burnt-out ruins of red brick buildings. The girl is partially naked; her upper body is bare, her lower body is clad in torn rags. Her face is dirty, her cheeks are burnt. Flaps of ruined skin hang off her arms and legs, revealing pale pink patches beneath.

This could be Vietnam, it could be Cambodia; it might be Serbia, Afghanistan, or the West Bank. It could be anywhere, at any time.

But it is England.

It is now.

The girl keeps on running even though the soles of her feet are worn away and bleeding. She feels no pain; she is beyond simple feelings. Her mother and father are dead. Her brothers and sisters have been blown apart by the bombs and bullets of an unknown enemy.

A single gunshot rings out and a bullet takes her down. The hair at the right side of her head puffs out, blood and brain and bone spatters in a vivid arc, spraying the grey ground red.

She falls, limp.

Dead.

The audience leans forward, trying to catch the girl; or they are just desperate to get a better view, a closer look at the blood and the carnage?

The music on the soundtrack soars, triumphant.

You try to close your eyes but you cannot. You have to see—you need to see this. There are things that must be endured, sights that cannot be ignored. You owe it to the girl; her lonely death must not go unwitnessed. So you sit there with your eyes forced open, taking it all in.

The screen goes dark. The lights come up.

“And that, ladies and gentlemen,” says a low, cultured voice through a hidden speaker, “is our little war project.”

A ripple of polite applause.

You grit your teeth.

When you glance down, at your hands, you see that you are clapping too, but you don’t know why, or for whom the applause is intended. The lights turn red and it looks like blood on your hands. You start to rub them together, but the stains remain.

When the lights flicker a signal for the end of the performance and the rest of the audience members start to leave, you pick up your bag from underneath your seat, stand, and walk out with them. You feel numb. Your skin is cold.

Out in the foyer a fat man in a black suit and John Lennon spectacles is shaking people’s hands, answering questions, and posing to have his photograph taken. He is the director, the creative mind behind the brief decontextualised images you have just seen.

“Thank you, thank you,” he says, soaking up the kudos, filling up with misplaced pride.

“When will the finished film be available to screen in full?” A local reporter jabs a digital tape recorder into the director’s fat face.

“Soon,” says the director. “Very soon.”

“What will it be called?”

The director opens his arms, lifts his head. “Cinder Images,” he says in a loud voice, making sure that everyone can hear. His eyes are bright behind the lenses of his glasses.

You consider approaching him to ask why you were invited to the screening, but then think better of such a rash move. It might draw attention to your discomfort. They might stare at you and see the fear that lies beneath your shell.

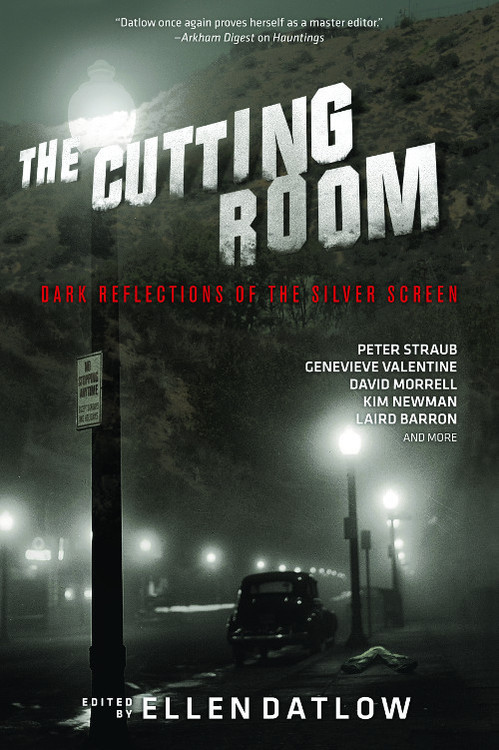

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.