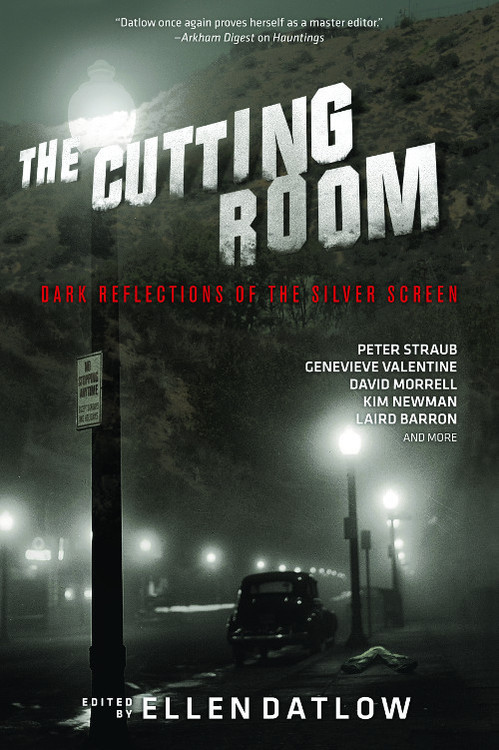

THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “Occam’s Ducks” by Howard Waldrop

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “Occam’s Ducks” by Howard Waldrop.

Producers Releasing Corporation Executive: Bill, you’re forty-five minutes behind your shooting schedule.

Beaudine: You mean someone’s waiting to see this crap??

—William “One Shot” Beaudine

For a week, late in the year 1919, some of the most famous people in the world seemed to have dropped off its surface.

The Griffith Company, filming the motion picture The Idol Dancer, with the palm trees and beaches of Florida standing in for the South Seas, took a shooting break.

The mayor of Fort Lauderdale invited them for a twelve-hour cruise aboard his yacht, the Gray Duck. They sailed out of harbor on a beautiful November morning. Just after noon a late-season hurricane slammed out of the Caribbean.

There was no word of the movie people, the mayor, his yacht, or the crew for five days. The Coast Guard and the Navy sent out every available ship. Two seaplanes flew over shipping lanes as the storm abated.

Richard Barthelmess came down to Florida at first news of the disappearance, while the hurricane still raged. He went out with the crew of the Great War U-boat chaser, the Berry Islands. The seas were so rough the captain ordered them back in after six hours.

The days stretched on: three, four. The Hearst newspapers put out extras, speculating on the fate of Griffith, Gish, the other actors, the mayor. The weather cleared and calm returned. There were no sightings of debris or oil slicks. Reporters did stories on the Marie Celeste mystery. Hearst himself called in spiritualists in an attempt to contact the presumed dead director and stars.

On the morning of the sixth day, the happy yachting party sailed back in to harbor.

First there were sighs of relief.

Then the reception soured. Someone in Hollywood pointed out that Griffith’s next picture, to be released nationwide in three weeks, was called The Greatest Question and was about life after death, and the attempts of mediums to contact the dead.

W. R. Hearst was not amused, and he told the editors not to be amused either.

Griffith shrugged his shoulders for the newsmen. “A storm came up. The captain put in at the nearest island. We rode out the cyclone. We had plenty to eat and drink, and when it was over, we came back.”

The island was called Whale Cay. They had been buffeted by the heavy seas and torrential rains the first day and night, but made do by lantern light and electric torches, and the dancing fire of the lightning in the bay around them. They slept stacked like cordwood in the crowded belowdecks.

They had breakfasted in the sunny eye of the hurricane late next morning up on deck. Many of the movie people had had strange dreams, which they related as the far-wall clouds of the back half of the hurricane moved lazily toward them.

Nell Hamilton, the matinee idol who had posed for paintings on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post during the Great War, told his dream. He was in a long valley with high cliffs surrounding him. On every side, as far as he could see, the ground, the arroyos were covered with the bones and tusks of elephants. Their cyclopean skulls were tumbled at all angles. There were millions and millions of them, as if every pachyderm that had ever lived had died there. It was near dark, the sky overhead paling, the jumbled bones around him becoming purple and indistinct.

Over the narrow valley, against the early stars a strange light appeared. It came from a searchlight somewhere beyond the cliffs, and projected onto a high bank of noctilucent cirrus was a winged black shape. From somewhere behind him a telephone rang with a sense of urgency. Then he’d awakened with a start.

Lillian Gish, who’d only arrived at the dock the morning they left, going directly from the Florida Special to the yacht, had spent the whole week before at the new studio at Mamaroneck, New York, overseeing its completion and directing her sister in a comedy feature. On the tossing, pitching yacht, she’d had a terrible time getting to sleep. She had dreamed, she said, of being an old woman, or being dressed like one, and carrying a Browning semiautomatic shotgun. She was being stalked through a swamp by a crazed man with words tattooed on his fists, who sang hymns as he followed her. She was very frightened in her nightmare, she said, not by being pursued, but by the idea of being old. Everyone laughed at that.

They asked David Wark Griffith what he’d dreamed of. “Nothing in particular,” he said. But he had dreamed: There was a land of fire and eruptions, where men and women clad in animal skins fought against giant crocodiles and lizards, much like in his film of ten years before, Man’s Genesis. Hal Roach, the upstart competing producer, was there, too, looking older, but he seemed to be telling Griffith what to do. D. W. couldn’t imagine such a thing. Griffith attributed the dream to the rolling of the ship, and to an especially fine bowl of turtle soup he’d eaten that morning aboard the Gray Duck, before the storm hit.

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.