THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “Tenderizer” by Stephen Graham Jones

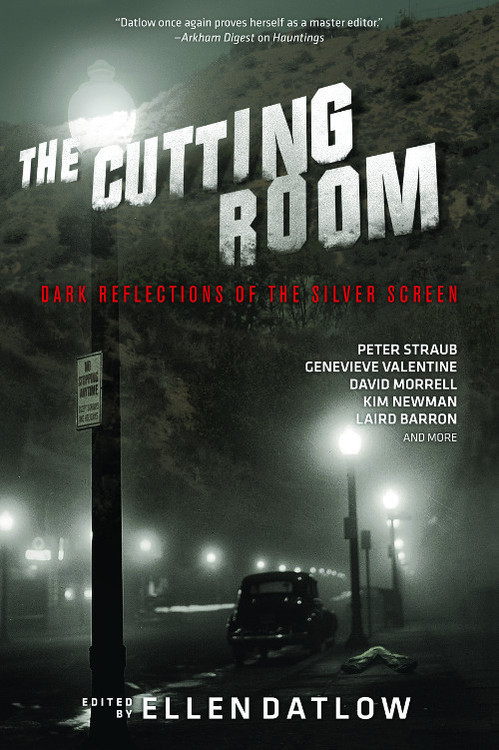

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “Tenderizer” by Stephen Graham Jones.

Brutal Is the Night: A Review

Remember The Blair Witch Project’s marketing campaign? It was an update of sorts on 1971’s The Last House on the Left, except where Wes Craven would have us keep reminding ourselves that it’s just a movie, it’s just a movie, Blair Witch kept whispering that this was actual found footage. It’s the same dynamic, though; it was tapping the same sensationalistic vein.

Writer/director Sean Mickles (Abasement, Thirty-Nine) knows this vein very well. And, for Tenderizer, he let it bleed.

As you probably recall, the first trailer was released as a “rough cut,” with the media outlets quoting Mickles’s grumbled objection that Tenderizer wasn’t ready, that production difficulties were built into a project like this, weren’t they?

Speculation was that he just wasn’t ready to let it go, of course.

It wouldn’t be the first time.

Whether actually released with his approval or not, that first trailer definitely had nerve. Just the title at lowest possible right in a “rough-cut” font, then ninety seconds of black screen, punctuated by shallow breathing, the kind that makes you hold your eyes a certain way, in sympathetic response. At the end of it there wasn’t even any large-sized title branded on or swooping in—there were no closing frames. It was all closing frames. It was as if a minute and a half of our pre-movie attractions had been hijacked. Watching it, you had the feeling you could look up at the theater’s tall back wall, see a prankster’s face smiling down at you from the projection booth.

Except that breathing, it was supposed to be actual recorded breathing. From one of the twenty-four victims of the Woodrow High School Massacre.

Neither Mickles nor Aklai Studio ever suggested it, but in the press surrounding the trailer’s release, Aklai did deny it, and not just in an oblique way, but in a way that felt coached. By a lawyer.

Mickles had no comment.

It was obvious he was part of this junket very much against his will.

Soon enough, another rumor found its way into circulation, from no source anybody could ever cite. But it was so terrible it had to be true. It was that that black screen, that nervous breathing, it was the last voicemail Mickles had received from his six-year-old daughter nearly ten years ago, when she was playing hide and seek with her nanny—when Mickles, according to the reports, assumed she was just carrying the cordless phone with her and had accidentally speed-dialed him.

Whether an intentional call or not, she still suffered the same fate: carbon monoxide in the garage, her new best hiding place.

The rumor about Tenderizer, then, was that Mickles was dealing with his own grief (or guilt) by exploring visuals that breathing could have been associated with, for a girl playing hide and seek on another ordinary day.

If either theory were true—the breathing was from a victim of the massacre, the breathing was from his own daughter’s accidental death—then the studio should have stopped the project right there. Aklai would have lost a few dollars, sure, but it would have gained some public opinion points, which are finally worth more.

Film is intensely personal, yes, and it can be violently pornographic, but playing either the labored breathing of someone now dead or the last missive from a daughter to a father, that’s combining the two in a way that shouldn’t be flirted with, right? Shouldn’t there be a line?

Apparently not.

Six months after that initial trailer, there was the soon-to-be-famous thirty-second spot—perhaps originally intended for network, for primetime—that featured footage culled from on-the-scene news reports, complete with station identifications, license plates, and sports logos blurred over. No, not blurred: smeared over. Instead of scrubbing the pixels or smudging the print, Mickles was showcasing his art-house pedigree. The news footage was playing on a small television, and the legally necessary “blurring” was actually Vaseline dabbed onto the screen. Which is to say those thirty seconds were shot, cut, and piped into a television monitor, then paused and rewound continually to wipe and reapply the Vaseline, a process that would have taxed even a Claymation artist’s patience. And for what effect, finally?

As with the rest of Sean Mickles’s body of work since his daughter’s accident, that’s always the question, yes.

Of course, save for one telltale glare of the screen right at the end of those thirty seconds, it takes a trained eye to even clock that it’s a television screen being filmed in the first place. Simply because of what that television is playing: thirty seconds of respondents and interviewees and witnesses to the Woodrow Massacre. Which of course we’ve all seen nearly to the point of memorization. Those easy, iconic moments weren’t the one Mickles chose for this trailer, though.

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.