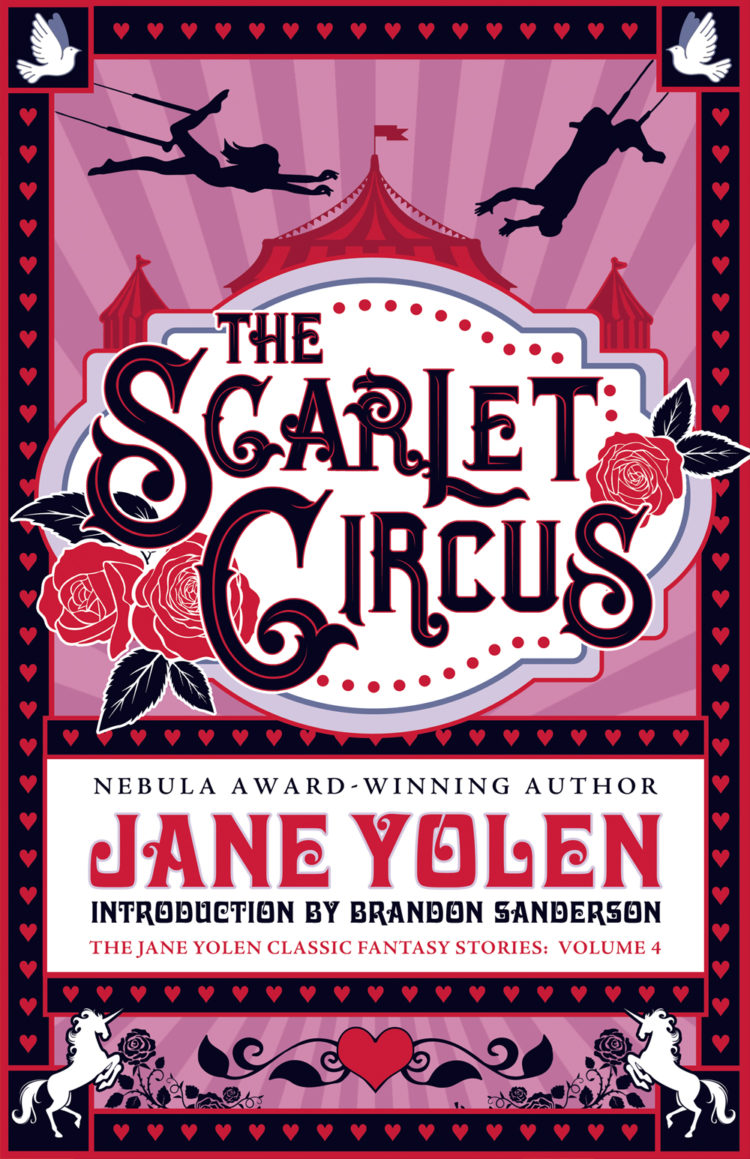

THE SCARLET CIRCUS by Jane Yolen preview: “Dusty Loves”

In celebration of the release of Jane Yolen’s THE SCARLET CIRCUS, Tachyon presents glimpses from the book that “is a magnificent and beautiful anthology from a master storyteller!” (Sarah Beth Durst, award-winning author of The Queens of Renthia series)

Dusty Loves

by

Jane Yolen

There is an ash tree in the middle of our forest on which my brother Dusty has carved the runes of his loves. Like the rings of its heartwood, the tree’s age can be told by the number of carvings on its bark. Dusty loves . . . begins the legend high up under the first branches. Then the litany runs like an old tale down to the tops of the roots. Dusty has had many, many loves, for he is the romantic sort. It is only in taste that he is wanting.

If he had stuck to the fey, his own kind, at least part of the time, Mother and Father would not have been so upset. But he had a passion for princesses and milkmaids, that sort of thing. The worst, though, was the time he fell in love with the ghost of a suicide at Miller’s Cross. That is a story indeed.

It began quite innocently, of course. All of Dusty’s affairs do. He was piping in the woods at dawn, practicing his solo for the Solstice. Mother and Father prefer that he does his scales and runs as far from our pavilion as possible, for his notes excite the local wood doves, and the place is stained quite enough as it is. Ever dutiful, Dusty packed his pipes and a cress sandwich and made for a Lonely Place. Our forest has many such: dells silvered with dew, winding streams bedecked with morning mist, paths twisting between blood-red trilliums—all the accoutrements of Faerie. And when they are not cluttered with bad poets, they are really quite nice. But Dusty preferred human highways and byways, saying that such busy places were, somehow, the loneliest places of all. Dusty always had a touch of the poet himself, though his rhymes were, at best, slant.

He had just reached Miller’s Cross and perched himself atop a standing stone, one leg dangling across the Anglo-Saxon inscription, when he heard the sound of human sobbing. There was no mistaking it. Though we fey are marvelous at banshee wails and the low-throbbing threnodies of ghosts, we have not the ability to give forth that half gulp, half cry that is so peculiar to humankind, along with the heaving bosom and the wetted cheek.

Straining to see through the early-morning fog, Dusty could just make out an informal procession heading down the road toward him. So he held his breath—which, of course, made him invisible, though it never works for long—and leaned forward to get a better view.

There were ten men and women in the group, six of them carrying a coffin. In front of the coffin was a priest in his somber robes, an iron cross dangling from a chain. The iron made Dusty sneeze, for he is allergic and he became visible for a moment until he could catch his breath again. But such was the weeping and carryings-on below him, no one even noticed.

The procession stopped just beneath his perch, and Dusty gathered up his strength and leaped down, landing to the rear of the group. At the moment his feet touched the ground, the priest had—fortuitously—intoned, “Dig!” The men had set the coffin on the ground and begun. They were fast diggers, and the ground around the stone was soft from spring rains. Six men and six spades make even a deep grave easy work, though it was hardly a pretty sight, and far from the proper angles. And all the while they were digging, a plump lady in gray worsted, who looked upholstered rather than dressed, kept trying to fling herself into the hole. Only the brawny arms of her daughters on either side and the rather rigid stays of her undergarments kept her from accomplishing her gruesome task.

At last the grave was finished, and the six men lowered the coffin in while the priest sprinkled a few unkind words over the box, words that fell on the ears with the same thudding foreboding as the clods of earth upon the box. Then they closed the grave and dragged the weeping women down the road toward the town.

Now Dusty, being the curious sort, decided to stay. He let out his breath once the mourners had turned their backs on him, and leaped up onto his perch again. Then he began to practice his scales with renewed vigor, and had even gotten a good hold on the second portion of “Puck’s Sarabande” when the moon rose. Of course, the laws of the incorporeal world being what they are, the ghost of the suicide rose, too. And that was when Dusty fell in love.