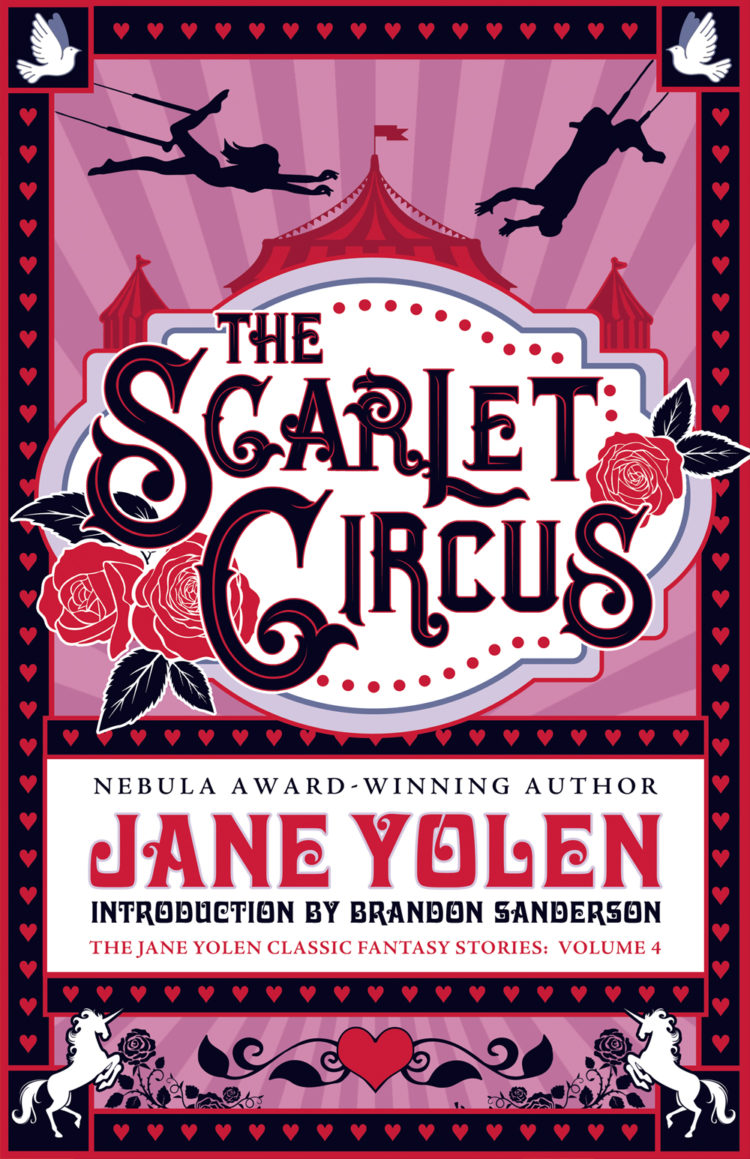

THE SCARLET CIRCUS by Jane Yolen preview: “Memoirs of a Bottle Djinn”

In celebration of the release of Jane Yolen’s THE SCARLET CIRCUS, Tachyon presents glimpses from the book that is “endlessly imaginative [with] superbly crafted tales that stir the heart.” (Kirkus)

Memoirs of a Bottle Djinn

by

Jane Yolen

In my country poets sing the praises of wine and gift its color to the water along the shores of Hellas, and I can think of no finer hymn. But in this land they believe their prophet forbade them strong drink. They are a sober race who reward themselves in heaven even as they deny themselves on earth. It is a system of which I do not approve, but then I am a Greek by birth and a heathen by inclination, despite mymaster’s long importuning. It is only by chance that I have not yet lost an eye, an ear, or a hand to my master’s unforgiving code. He finds me amusing, but it has been seven years since I have had a drink.

I stared at the bottle. If I had any luck at all, the bottle had fallen from a foreign ship and its contents would still be potable. But then, if I had any luck at all, I would not be a slave in Arabia, a Greek sailor washed up on these shores, the same as the bottle at my feet. My father, who was a cynic like his father before him, left me with a cynic’s name—Antithias—a wry heart, and an acid tongue, none proper legacies for a slave.

But as blind Homer wrote, “Few sons are like their father; many are worse.” I guessed that the wine, if drinkable, would come from an inferior year. And with that thought, I bent to pick it up.

The glass was a cloudy green, like the sea after a violent storm. Like the storm that had wrecked my ship and cast me onto a slaver’s shore. There were darker flecks along the bottom, a sediment that surely foretold an undrinkable wine. I let the bottle warm between my palms.

Since the glass was too dark to let me see more, I waited past my first desire and was well into my second, letting itrise up in me like the heat of passion. The body has its own memories, though I must be frank: passion, like wine, was simply a fragrance remembered. Slaves are not lent the services of concubines, nor was one my age and race useful for breeding. It had only been by feigning impotence that I had kept that part of my anatomy intact—another of my master’s unforgiving laws. Even in the dark of night, alone on my pallet, I forwent the pleasures of the hand, for there were spies everywhere in his house and the eunuchs were a notably gossipy lot. Little but a slave’s tongue lauding morality stood between gossip and scandal, stood between me and the knife. Besides, the women of Arabia tempted me little. They were like the bottle in my hand—beautiful and empty. A wind blowing across the mouth of each could make them sing, but the tunes were worth little. I liked my women like my wine—full-bodied and tanged with history, bringing a man into poetry. So I had put my passion into work these past seven years, slave’s work though it was. Blind Homer had it right, as usual: “Labor conquers all things.” Even old lusts for women and wine.

Philosophy did not conquer movement, however, and my hand found the cork of the bottle before I could stay it. With one swift movement I had plucked the stopper out. A thin strand of smoke rose into the air. A very bad year indeed, I thought, as the cork crumbled in my hand.

Up and up and up the smoky rope ascended and I, bottle in hand, could not move, such was my disappointment. Even my father’s cynicism and his father’s before him had not prepared me for such a sudden loss of all hope. My mind, a moment before full of anticipation and philosophy, was now in blackest despair. I found myself without will, reliving in my mind the moment of my capture and the first bleak days of my enslavement.

That is why it was several minutes before I realized that the smoke had begun to assume a recognizable shape above the bottle’s gaping mouth: long, sensuous legs glimpsed through diaphanous trousers; a waist my hands could easily span; breasts beneath a short