THE VERY BEST OF CAITLÍN R. KIERNAN preview: “The Ammonite Violin (Murder Ballad No. 4)”

In celebration for the release of THE VERY BEST OF CAITLÍN R. KIERNAN, Tachyon presents glimpses from some of the volume’s strange and macabre tales by the “reigning queen of dark fantasy.”

The

Ammonite Violin (Murder Ballad No. 4)

by Caitlín R. Kiernan

“It

must be done precisely

as I have said,” he told the violin-maker, four months ago, when he

flew to Hotton to hand-deliver a substantial portion of the materials

from which the instrument would be constructed. “You may not

deviate in any significant way from these instructions.”

“Yes,”

the luthier replied, “I understand. I understand completely.” A

man who appreciates discretion, the Belgian violin-maker, so there

were no inconvenient questions asked, no prying inquiries as to why,

and what’s more, he’d even known something about ammonites

beforehand.

“No

substitutions,” the Collector said firmly, just in case it needed

to be stated one last time.

“No

substitutions of any sort,” replied the luthier.

“And

the back must be carved—”

“I

understand,” the violin-maker assured him. “I have the sketches,

and I will follow them exactly.”

“And

the pegs—”

“Will

be precisely as we have discussed.”

And

so the Collector paid the luthier half the price of the commission,

the other half due upon delivery, and he took a six a.m. flight back

across the wide Atlantic to New England and his small house in the

small town near the sea. And he has waited, hardly daring to

half-believe

that the violin-maker would, in fact, get it all right. Indeed—for

men are ever at war with their hearts and minds and innermost

demons—some infinitesimal scrap of the Collector has even hoped

that there would

be a mistake, the most trifling portion of his plan ignored or the

violin finished and perfect but then lost in transit and so the whole

plot ruined. For it is no small thing, what the Collector has set in

motion, and having always considered himself a very wise and sober

man, he suspects that he understands fully the consequences he would

suffer should he be discovered by lesser men who have no regard for

the ocean and her needs. Men who cannot see the flesh and blood

phantoms walking among them in broad daylight, much less be bothered

to pay tithes which are long overdue to a goddess who has cradled

them all, each and every one, through the innumerable twists and

turns of evolution’s crucible, for three and a half thousand

million years.

But

there has been no mistake, and, if anything, the violin-maker can be

faulted only in the complete sublimation of his craft to the will of

his customer. In every way, this is the instrument the Collector

asked him to make, and the varnish gleams faintly in the light from

the display cases. The top is carved from spruce, and four small

ammonites have been set into the wood—Xipheroceras

from Jurassic rocks exposed along the Dorset Coast at Lyme Regis—two

inlaid on the upper bout, two on the lower. He found the fossils

himself, many years ago, and they are as perfectly preserved an

example of their genus as he has yet seen anywhere, for any price.

The violin’s neck has been fashioned from maple, as is so often the

tradition, and, likewise, the fingerboard is the customary ebony.

However, the scroll has been formed from a fifth ammonite, and the

Collector knows it is a far more perfect logarithmic spiral than any

volute that could have ever been hacked out from a block of wood. In

his mind, the five ammonites form the points of a pentacle. The

luthier used maple for the back and ribs, and when the Collector

turns the violin over, he’s greeted by the intricate bas-relief he

requested, faithfully reproduced from his own drawings—a great

octopus, the ravenous devilfish of so many sea legends, and the maze

of its eight tentacles makes a looping, tangled interweave.

As

for the pegs and bridge, the chinrest and tailpiece, all these have

been carved from the bits of bone he provided the luthier. They seem

no more than antique ivory, the stolen tusks of an elephant or a

walrus or the tooth of a sperm whale, perhaps. The Collector also

provided the dried gut for the five strings, and when the

violin-maker pointed out that they would not be nearly so durable as

good stranded steel, that they would be much more likely to break and

harder to keep in tune, the Collector told him that the instrument

would be played only once and so these matters were of very little

concern. For the bow, the luthier was given strands of hair which the

Collector told him had come from the tail of a gelding, a fine grey

horse from Kentucky thoroughbred stock. He’d even ordered a special

rosin, and so the sap of an Aleppo Pine was supplemented with a vial

of oil he’d left in the care of the violin-maker.

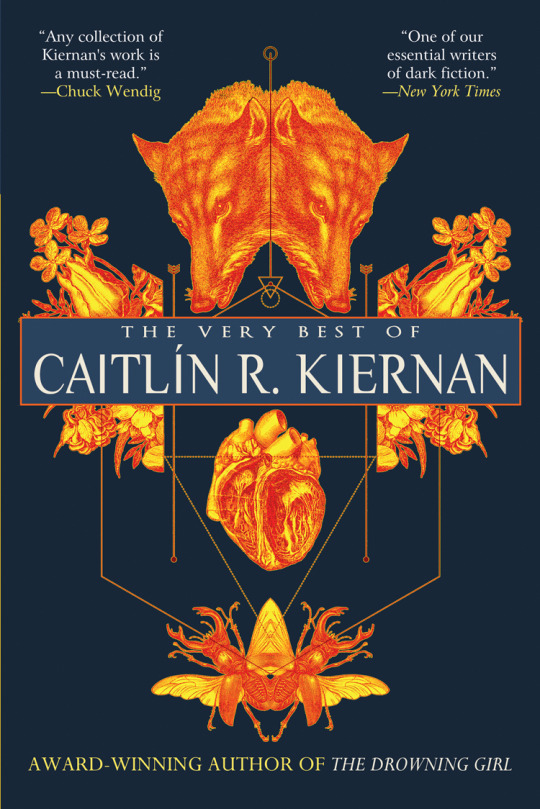

For more info about THE VERY BEST OF CAITLÍN R. KIERNAN, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Hannes Hummel

Design by Elizabeth Story