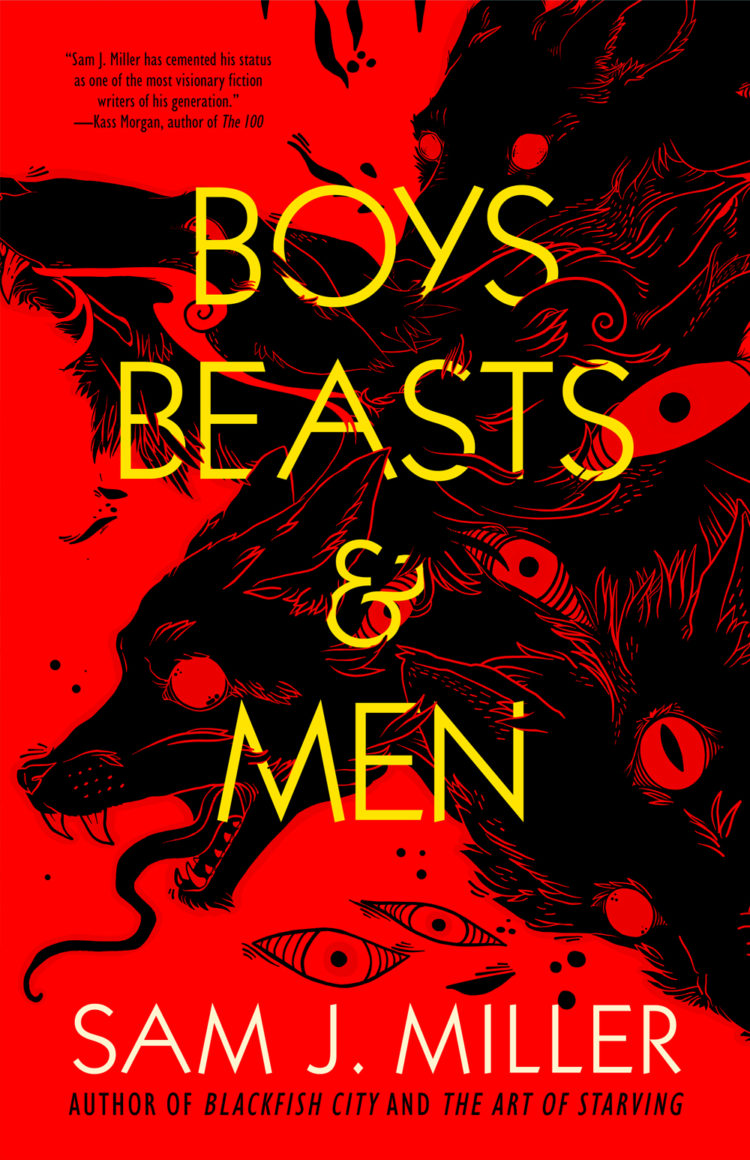

BOYS, BEASTS & MEN by the award-winning Sam J. Miller preview: “The Heat of Us: Notes Toward an Oral History”

In celebration of the release of Sam J. Miller’s debut collection BOYS, BEASTS & MEN, Tachyon presents glimpses from the new collection.

Miller’s sheer talent shines through in abundance . . . Boys, Beasts & Men is an outrageous journey which skillfully blends genres and will haunt you with its original, poetic voices as much as its victims, villains, and treasure trove of leading actors.

—Grimdark Magazine

Design by Elizabeth Story

The Heat of Us: Notes Toward an Oral History

by

Sam J. Miller

Craig Perry, university administration employee.

Judy Garland, dead. That’s where it started. Dead five days before, in London, “an incautious overdosage” of barbiturates, according to the coroner, and her body had just come back to New York for burial. Twenty-thousand people lined up to pay their respects. Every gay man in Manhattan must have gone, but I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t go see her in that coffin and disturb the delicate Dorothy Gale I had in my head. I don’t know, I needed to move, to walk, to run. To do something. So I headed for the Hudson River Piers.

My sadness buoyed me up, made me feel like I was looking down on the entire city. I watched the sky go blue and orange and red and purple and indigo as the sun set, then watched the lights come on across the river in Jersey City. June, 1969: The wet Manhattan air was like sick breath coming out of our collective throat.

I felt it in me, then. A spark. I didn’t see it for what it really was, but I felt it.

That’s why I went to the Stonewall.

Sadness is a better spark than rage. I remember thinking, Revolutions are born on nights like this. So many people would be mourning Judy. We’d all be miserable together. What couldn’t we do, if we were all on the same page like that? Now it sounds like I’m trying to be portentous, given what ultimately went down that night, but I really did have that feeling.

Ben Lazzarra, NYPD beat cop.

I checked with the sarge that afternoon. I always did, when I was off-duty and felt the urge and knew I couldn’t fight it, knew I’d have to find a place to dance it out of me. I was lucky I was a cop and could check to make sure I wouldn’t get swept up in a raid. Nothing was on the list for the Stonewall that night. That’s how I know for a fact that what went down that night was not your standard gay club raid. Someone upstairs was pulling strings.

I spent the whole week agonizing over whether or not to go. That’s how it always went. I’d wrestle with my fear and shame, and win, and go, and then feel so miserable and ashamed afterwards that I leapt back into the closet for another few weeks. I needed some action, some booze, and some sweat and some sex with a stranger. Quentin and I had gone to the gym together, that afternoon, and I knew he had to work that night. He didn’t ask where I was going, when I went out. Even twins are allowed to have little secrets. But he was the reason I stayed in the closet, and was always so careful to not get dragnetted. Seeing my name in the paper in a story on a gay bar raid—that would kill Quentin quicker and deader than any bullet.

The world changed in two huge ways that night.

In the first place, the world changed because the gays fought back. The police and the press were equally dumbfounded by the idea that a bar full of fairies would refuse to submit to one of the raids that were standard—if monstrously unjust—operating procedure. The Stonewall itself had been raided less than a week before. The night of June 28, 1969, should have been no different.

Secondly, the Stonewall Uprising was the first public demonstration of the supernatural phenomenon that would later be called by names as diverse as collective pyrokinesis, group magic, communal energy, polykinesis, multipsionics, liberation flame, and hellfire.

None of the eleven different city, state, and federal government agencies that investigated the events of that night have ever confirmed or even acknowledged the overwhelming number of witness testimonies describing the events that caused the police to so catastrophically lose control of a routine operation. The facts, however, do not seem to be in doubt. Ten police officers were vaporized that night, vanishing so utterly that the NYPD still considers them missing persons. Three more were cooked alive, charred to the point where dental records were needed to identify the bodies. No incendiary or flammable substances were found at the scene. Five paddy wagons full of arrestees were stopped when their engines spontaneously overheated, and the metal doors of the wagons were melted away to free the people inside—yet no blowtorches or welding equipment were found at the scene.

Since testimonials are all that’s left to those of us frustrated with the Official Version, the oral history format seems to be our best bet. I know that many of the most outspoken voices of the Stonewall Uprising have reacted with anger and hostility at the news that I, of all journalists, was planning to compile such a history, and are urging their comrades not to speak with me. I understand their objections, and have precious little to show by way of proof that I’ve changed. I simply cannot not tell this story.

—Jenny Trent, Editor (formerly of The New York Times)