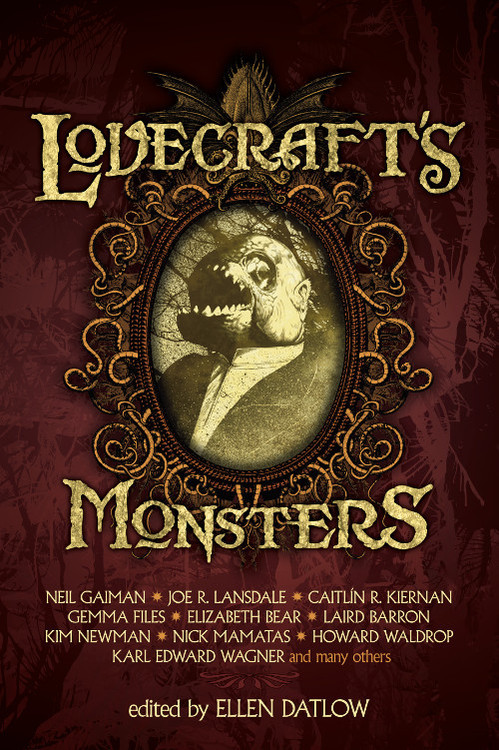

LOVECRAFT’S MONSTERS preview: “The Dappled Thing” by William Browning Spencer

Over the next two weeks in celebration of the forthcoming Lovecraft’s Monsters, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “The Dappled Thing” by William Browning Spencer.

It was the dry season, a relative term, and Rudge cursed a so-called dry season that could grow mold on a man’s skin and generated a pale mist in which monsters seemed to lurk.

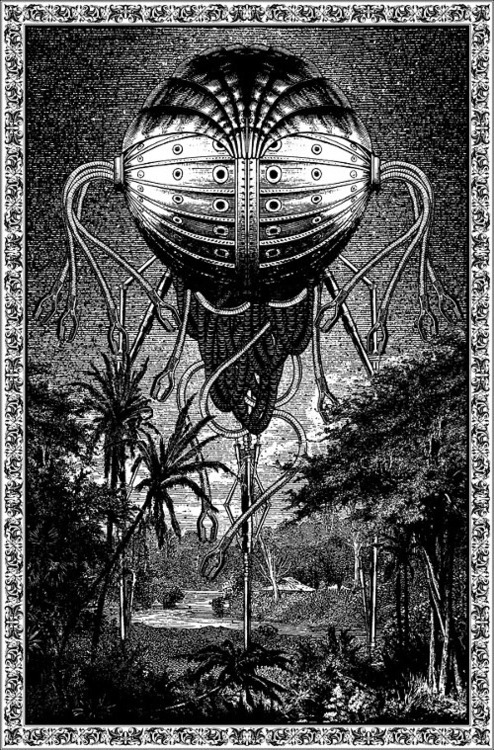

Their progress through this world was loud and violent. Her Glory of Empire was not designed for stealth. It moved by thrashing and sawing its way through the jungle, pulling trees down or climbing them like an ungainly spider until they bent beneath its weight. Sometimes monkeys would scream from the trees, following the vehicle for days, hooting with outrage or, perhaps, a kind of carnival glee, delighting in destruction, as Rudge had seen men do in the frenzy of war.

He was fascinated with Her Glory of Empire, but there was something about the machine that he distrusted. It was, Rudge thought, against Nature, by which he did not mean that it was some kind of Devil’s work, but that, being fashioned by immutable physical laws, and, consequently, itself a creature of Nature, its destruction of the natural world seemed a perversity, a subverting of those laws God had stamped on His Creation. Rudge could not have explained this to anyone, and if, somehow, he had managed to voice his reservations, no one would have taken him seriously. They would have been amused, would have seen him as some foolish old codger at odds with inevitable change.

Well, he was old and set in his ways. Maybe that was all there was to it.

On the eleventh day of travel beyond the site of the burned zeppelin, they had a bit of good luck. They came upon a small village of round huts, a village they might have passed if the cacophony of their passage hadn’t attracted the natives, who were friendly and showed some acquaintance with civilization, even to the point of wearing clothing and emulating Jesus by pushing thorns into the palms of their hands. Rudge’s manservant, Jacobs, had a gift with languages, or, more precisely, communication itself. A small, swarthy man, Jacobs possessed a gray explosive mustache that suggested belligerence, but he was, in fact, as calm as a cat, and capable of getting the meaning from any human being with vocal chords.

After talking at length to the village elder, Jacobs was able to relate the good news. Wallister’s party had passed this way heading north. “He says he warned them about the Yami, but they seemed unperturbed on that score,” Jacobs said. He added, “The old fella says he thought they might have been earth or water spirits because they didn’t know things that even a child knows.”

Rudge asked what that would be.

“He said they didn’t know that they could die.”

The next day, they ate lunch in a small clearing with a bright stream running through it. The stream was bordered by thin pale-green trees and lush black-green ferns. When Rudge went off to relieve his bladder by the edge of the forest, tiny blue butterflies fluttered around the stream of his urine and settled on the wet grass as though he were spilling a rare elixir.

When he returned, Rudge found Tommy Strand sitting by the brook. Strand started declaiming immediately, as though Rudge’s presence required it. It was another poem:

“Glory be to God for dappled things,

For skies of couple-color as a brinded cow,

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls, finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced, fold, fallow and plough…”

It went on like that for a while. Rudge thought the verse was apt enough: a jungle was definitely dappled, light tumbling through the leaves, water, always moving, the light within it alive, mottled and animate. But it was a stretch to compare the sky to a cow. Poets often did that: started out well enough but then let go of the reins, let language get the best of them in their zeal.

Strand said the poem was by a fellow named Manly Hopkins. Rudge didn’t think of poets as being all that manly, except for that Kipling fellow who had some grit in his lines and knew how to tell a story.

For more information on Lovecraft’s Monsters, visit the Tachyon site.

Cover and illustration by John Coulthart.