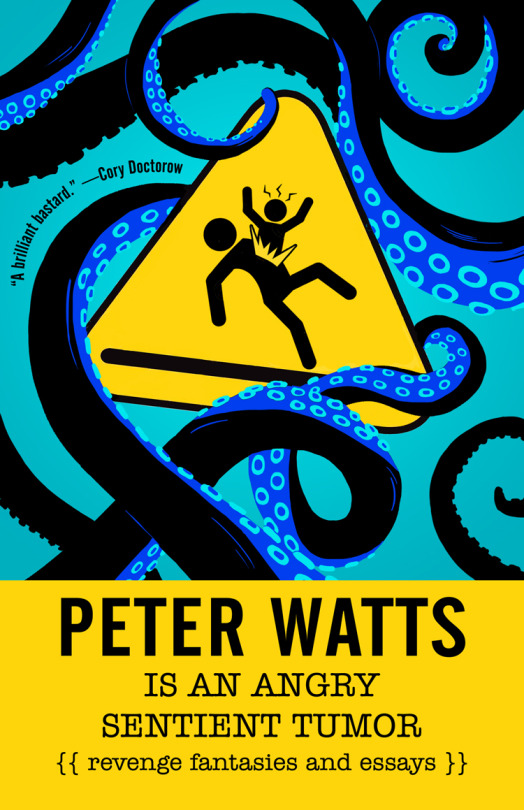

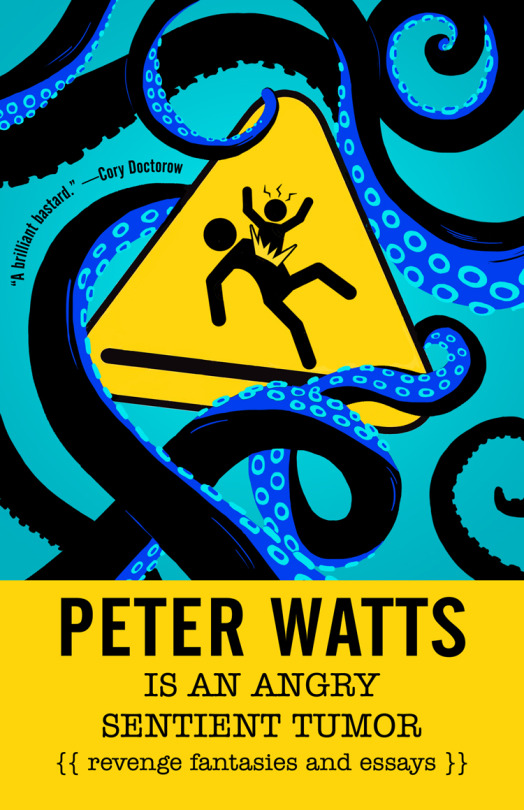

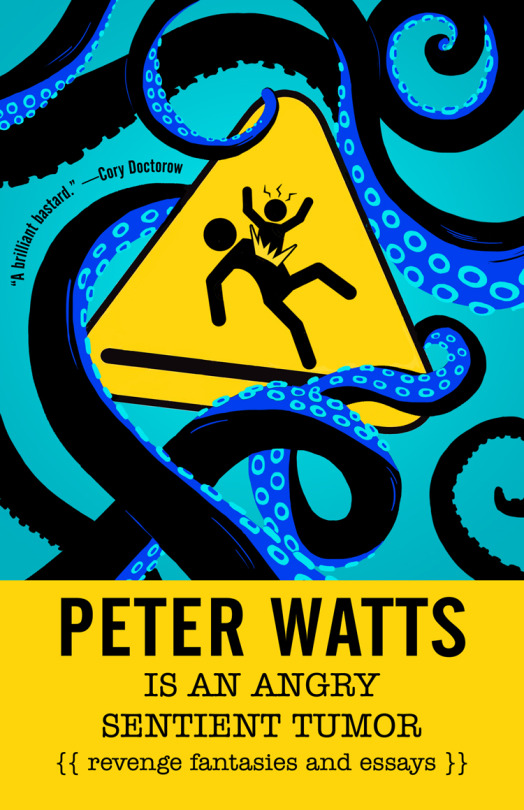

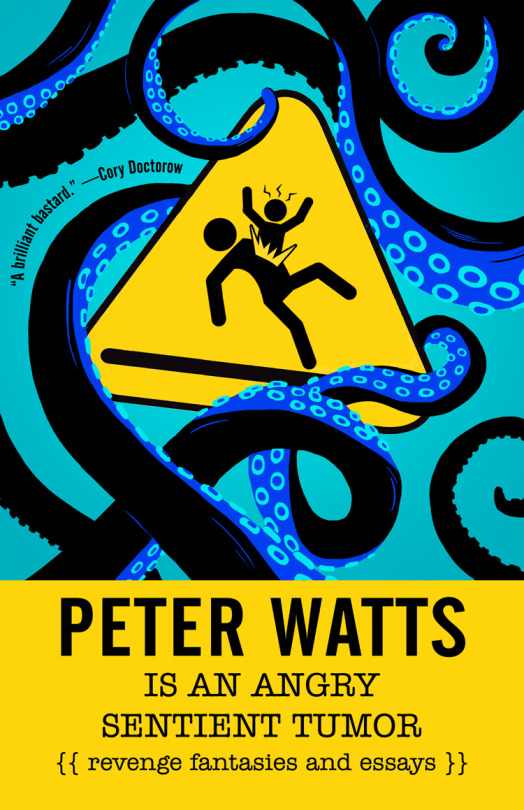

PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR preview: “No Brainer”

In celebration for the release of the irreverent, self-depreciating, profane, and funny PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, Tachyon presents glimpses from the essay collection.

No Brainer

by

Peter Watts

Nowa Fantastyka May 2015

Blog Jul 28 2015

For

decades now, I have been haunted by the grainy, black-and-white x-ray

of a human skull.

It

is alive but empty, with a cavernous fluid-filled space where the

brain should be. A thin layer of brain tissue lines that cavity like

an amniotic sac. The image hails from a 1980 review

article in Science: Roger Lewin, the author, reports that

the patient in question had “virtually no brain”i.

But that’s not what scared me; hydrocephalus is nothing new, and it

takes more to creep out this ex-biologist than a picture of

Ventricles Gone Wild.

What

scared me was the fact that this virtually brain-free patient had an

IQ of 126.

He

had a first-class honors degree in mathematics. He presented normally

along all social and cognitive axes. He didn’t even realize there

was anything wrong with him until he went to the doctor for some

unrelated malady, only to be referred to a specialist because his

head seemed a bit too large.

It

happens occasionally. Someone grows up to become a construction

worker or a schoolteacher, before learning that they should have been

a rutabaga instead. Lewin’s paper reports that one out of ten

hydrocephalus cases are so extreme that cerebrospinal fluid fills 95%

of the cranium. Anyone whose brain fits into the remaining 5% should

be nothing short of vegetative; yet apparently, fully half have IQs

over 100. (Why, here’s another

example from 2007ii;

and yet another.iii)

Let’s call them VNBs, or “Virtual No-Brainers.”

The

paper is titled “Is Your Brain Really Necessary?”, and it seems

to contradict pretty much everything we think we know about

neurobiology.

This Forsdyke guy over in Biological Theory argues

that such cases open the possibility that the brain might utilize

some kind of extracorporeal storageiv,

which sounds awfully woo both to me and to the anonymous

neuroskeptic over at Discovery.comv;

but even Neuroskeptic, while dismissing Forsdyke’s wilder

speculations, doesn’t really argue with the neurological facts on

the ground. (I myself haven’t yet had a chance to more than glance

at the Forsdyke paper, which might warrant its own post if it turns

out to be sufficiently substantive. If not, I’ll probably just

pretend it is and incorporate it into Omniscience.)

On a

somewhat less peer-reviewed note, VNBs also get routinely trotted out

by religious nut jobs who cite them as evidence that a God-given soul

must be doing all those things the uppity scientists keep attributing

to the brain. Every now and then I see them linking to an off-hand

reference I made way back in 2007 (apparently rifters.com is the

only place to find Lewin’s paper online without having to pay a

wall) and I roll my eyes.

And

yet, 126 IQ. Virtually no brain. In my darkest moments of doubt, I

wondered if they might be right.

So

on and off for the past twenty years, I’ve lain awake at night

wondering how a brain the size of a poodle’s could kick my ass at

advanced mathematics. I’ve wondered if these miracle freaks might

actually have the same brain mass as the rest of us, but

squeezed into a smaller, high-density volume by the pressure of all

that cerebrospinal fluid (apparently the answer is: no). While I was

writing Blindsight—having learned that cortical modules in

the brains of autistic savants are relatively underconnected, forcing

each to become more efficient—I wondered if some kind of

network-isolation effect might be in play.

Now,

it turns out the answer to that is: Maybe.

Three

decades after Lewin’s paper, we have “Revisiting

hydrocephalus as a model to study brain resilience” by de

Oliveira et alvi

(actually published in 2012, although I didn’t read it until last

spring). It’s a “Mini Review Article”: only four pages, no new

methodologies or original findings—just a bit of background, a

hypothesis, a brief “Discussion” and a conclusion calling for

further research. In fact, it’s not so much a review as a challenge

to the neuro community to get off its ass and study this fascinating

phenomenon—so that soon, hopefully, there’ll be enough new

research out there warrant a real review.

The

authors advocate research into “Computational models such as the

small-world

and scale-free

network”—networks whose nodes are clustered into

highly-interconnected “cliques”, while the cliques themselves are

more sparsely connected one to another. De Oliveira et al

suggest that they hold the secret to the resilience of the

hydrocephalic brain. Such networks result in “higher dynamical

complexity, lower wiring costs, and resilience to tissue insults.”

This also seems reminiscent of those isolated hyper-efficient modules

of autistic savants, which is unlikely to be a coincidence: networks

from social to genetic to neural have all been described as

“small-world.” (You might wonder—as I did—why de Oliveira et

al. would credit such networks for the normal intelligence of

some hydrocephalics when the same configuration is presumably

ubiquitous in vegetative and normal brains as well. I can only assume

they meant to suggest that small-world networking is especially

well-developed among high-functioning hydrocephalics.) (In all

honesty, it’s not the best-written paper I’ve ever read.)

The

point, though, is that under the right conditions, brain damage

may paradoxically result in brain enhancement. Small-world,

scale-free networking—focused, intensified, overclocked—might

turbocharge a fragment of a brain into acting like the whole thing.

Can

you imagine what would happen if we applied that trick to a normal

brain?

If

you’ve read Echopraxia, you’ll remember the Bicameral

Order: the way they used tailored cancer genes to build extra

connections in their brains, the way they linked whole brains

together into a hive mind that could rewrite the laws of physics in

an afternoon. It was mostly bullshit, of course: neurological

speculation, stretched eight unpredictable decades into the future

for the sake of a story.

But

maybe the reality is simpler than the fiction. Maybe you don’t have

to tweak genes or interface brains with computers to make the next

great leap in cognitive evolution. Right now, right here in the real

world, the cognitive function of brain tissue can be boosted—without

engineering, without augmentation—by literal orders of magnitude.

All it takes, apparently, is the right kind of stress. And if the

neuroscience community heeds de Oliveira et al’s clarion

call, we may soon know how to apply that stress to order. The

singularity might be a lot closer than we think.

Also

a lot squishier.

Wouldn’t

it be awesome if things turned out to be that easy?

i

http://rifters.com/real/articles/Science_No-Brain.pdf

ii

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61127-1

iii

http://mymultiplesclerosis.co.uk/ep/sharon-parker-the-woman-with-the-mysterious-brain/

iv

http://rifters.com/real/articles/Forsdyke-2015-BrainScansofHydrocephalicsChallengeCherishedAssumptions.pdf

v

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/neuroskeptic/2015/07/26/is-your-brain-really-necessary-revisited/

vi

http://rifters.com/real/articles/Oliveira-et-al-2012-RevisitingHydrocephalus.pdf

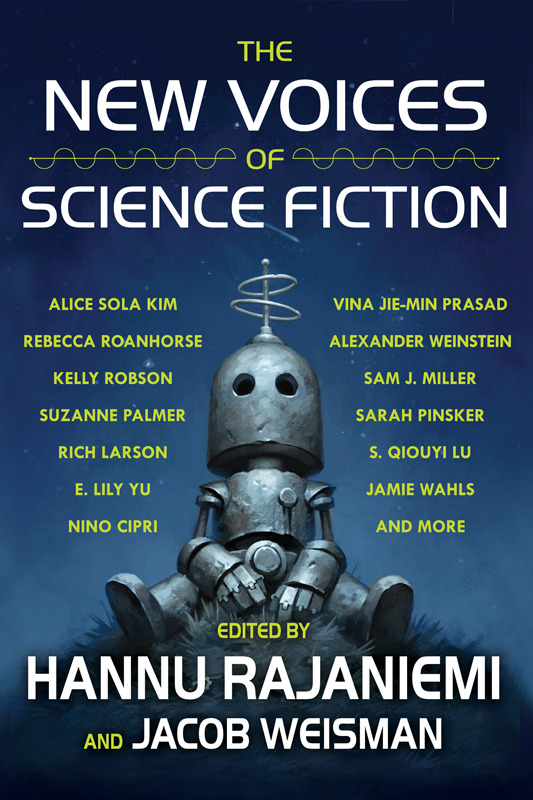

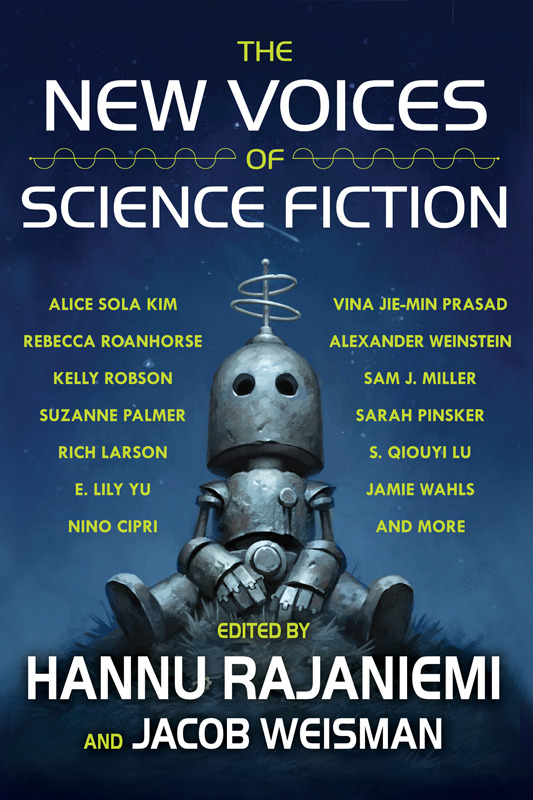

For more info about PETER WATTS IS AN ANGRY SENTIENT TUMOR, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover design by Elizabeth Story

Icon by John Coulthart