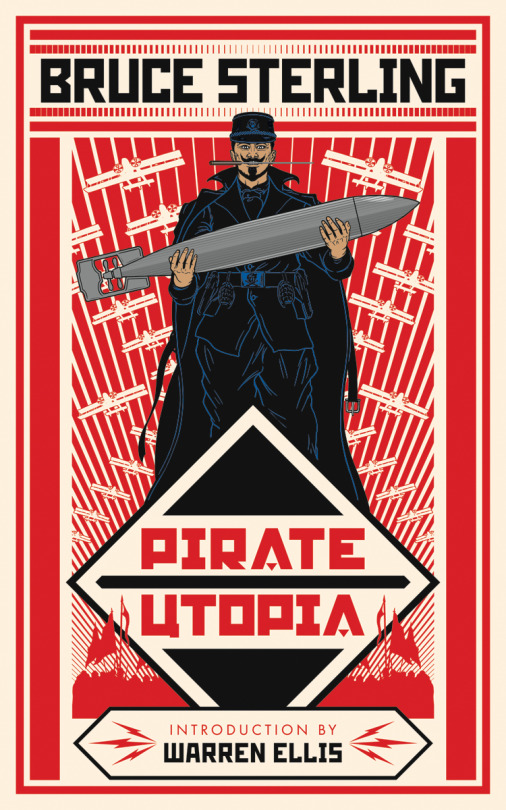

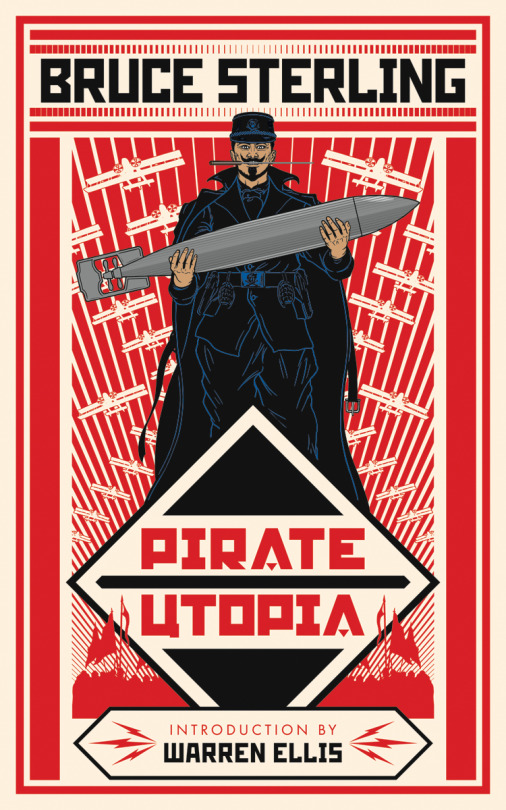

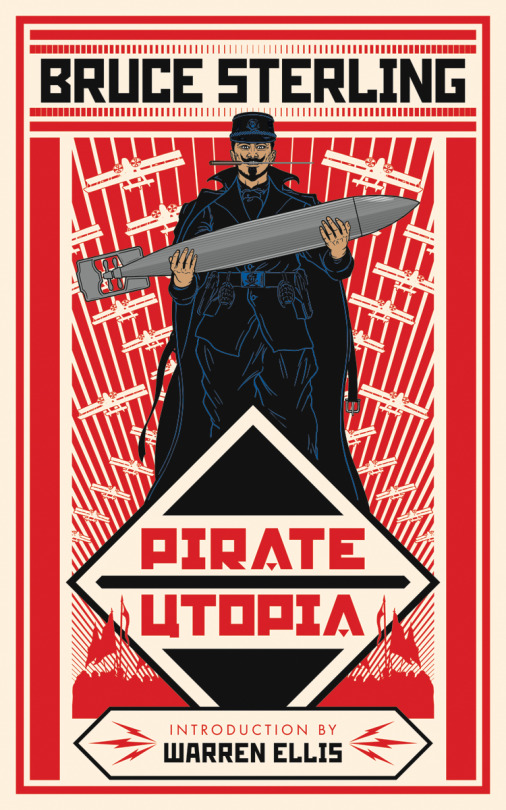

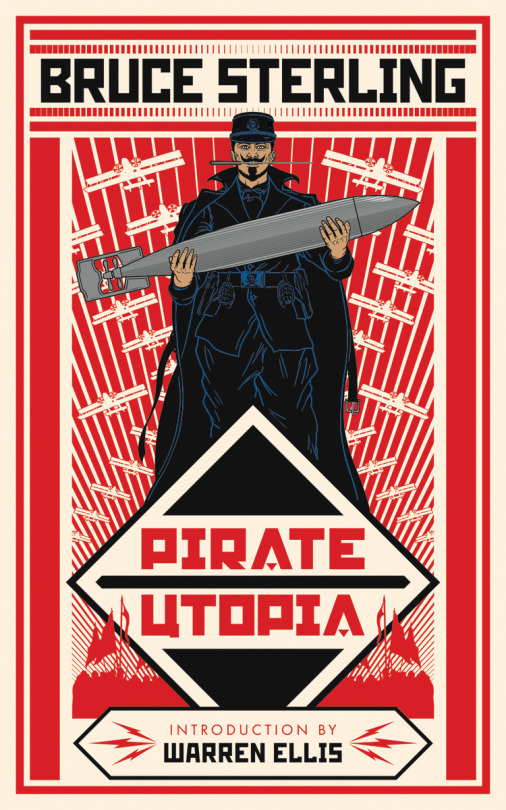

The highly recommended PIRATE UTOPIA is a delightfully odd read

Four fresh reviews for Bruce Sterling’s entertaining and thoughtful PIRATE UTOPIA.

THE WARBLER praises the book.

Bruce Sterling’s PIRATE UTOPIA is a delightful and odd read. It is a fine work of alternate history focused on a particularly odd time in a little-known city in Europe after the Great War. Because the story of Fiume is so obscure (or, at least was completely unknown to me prior to reading PIRATE UTOPIA), it reads more like historical fantasy than alternate history, and had me pausing regularly to look up people and places I’d never heard of before.

<snip>

Sterling’s writing conjured an amalgam of Miyazaki (particularly because of PORCO ROSSO, which is set in the Adriatic) and THE TRIPLETS OF BELLEVILLE, for its surreality and darkness. It’s a book driven not by plot but by character and setting, which have enough going for them to make it a riveting read. The cast have deeply held principles, they’re people of action, deep thinkers, artists, revolutionaries!

But they’re also absurd, in their own way. In a gratifying way. They’re almost caricatures, but I don’t think they’d be that far off from the real thing, given the immense shifts in technology and thought taking place in the twenties. What must it have been like, to be on tons of cocaine and working on radio-controlled weapons and casting down the archaic notions of the past, forging on to a future lit by the fires of industry and war? The thought is intoxicating to some of the characters, even more than the intoxicants themselves.

PIRATE UTOPIA is strange fiction about a time and zeitgeist that may be stranger than the fiction itself. It made me want to discover other odd spandrels left by massive leaps and changes in the world. Was there ever a similar free state nestled in the Americas? In Eurasia? In Africa? Things like Cargo Cults in the pacific, the strange results of colliding culture and knowledge…that’s what PIRATE UTOPIA piqued in my mind.

So, absolutely get this book. Then, maybe join me in a deep dive through Wikipedia to find more cool moments in history.

Benjamin Gabriel for STRANGE HORIZONS examines the story.

Before reading PIRATE UTOPIA, I was completely unfamiliar with the history of the Regency of Carnaro (aka Fiume), and there is something to be said about how that affected my enjoyment of Bruce Sterling’s latest Italian adventure. With no knowledge of the historical import, the political pillars of the novella—and I should say clearly that, like most of Sterling’s recent fiction, it is the politics that are primarily of interest here—were much more malleable. Rather than seeing this as a treatise or a partisan attack, I was able to see in it something I could work with: if you’re looking for a simple positive or negative recommendation (and to avoid spoilers), the only thing you might otherwise need is the knowledge that PIRATE UTOPIA is the best of Bruce Sterling’s recent Italian work (including BLACK SWAN and THE PARTHENOPEAN SCALPEL [both 2010]). The short version of the history to which PIRATE UTOPIA offers an alternative, though, is this: in 1919, poet and war hero Gabriele D’Annunzio occupied a small Balkan city called Fiume after the League of Nations gave it to Yugoslavia, intending to annex it for Italy. He instead ended up creating a cobbled-together state that reveled in aesthetic and anarchist practices, as well as becoming a hotbed for fascism—most notably by introducing Mussolini to the Roman Salute with which Adolf Hitler would go on to be associated.

<snip>

PIRATE UTOPIA finds publication at a strange moment in history, both politically and aesthetically. The former correlations are perhaps obvious: the global wave of populist revolt that followed the 2008 economic crisis has broken, and once again the jetsam of fascism is more and more rapidly being revealed. Trump and Brexit have become the bellwethers, but they have only taken over for the Golden Dawn and many others. Now is perhaps the worst possible time to release a novella that uncritically replicates the ideology of the Historical Man in a way that could easily be read as an apologia for the historical moment we may well have cycled back into. But simply stating that is meaningless moralizing. It is our concurrent strange aesthetic moment that complicates and crystallizes PIRATE UTOPIA.

<snip>

And the author’s history provides no real alibi. From cyberpunk to steampunk to slipstream, from design fiction writer and Wired blogger to wandering futurist, Sterling’s Midas touch is to turn all he touches into markets. Sometimes that means erasing the recent history of women’s writing, other times advocating for what amounts (in John Clute’s words) to “commercial piggybacking.” None of this is to say that he hasn’t done admirable work as well, especially around taking seriously climate change in fiction. Even as a writer whose material actions against which I often take umbrage, he remains a storyteller who is invested in taking the political elements of his work seriously and crafting them into something both entertaining and thoughtful.

On EL BLOG DE BORGES, Puerto Rican writer José

Borges praises the work.

The author tells the novel through short chapters, in which he manages to get a good feel for the complex scenario in which the plot unfolds. With the use of repetitions and simple language, it gives voice to avant-garde poets who recite poetry, use drugs and fight to the death for their ideals.

It’s an interesting read with a non-traditional ending. It plays with elements of the past within a context that could well apply to our contemporary era in some respects. Part of what makes it interesting is that it will force readers to find out what the true story was and how it unfolds in the novel. Although it may not please every reader, it invites you to test the waters of these pirate engineers who want to bring the future to wherever possible, regardless of whether it’s bombs or bullets.

(Translation from Spanish courtesy of Google)

Ian Campbell at MEDIUM enjoys PIRATE UTOPIA.

PIRATE UTOPIA’s a short, fun read that doesn’t alternate between stark and wacky but manages to hold their continuing tension in exquisite and exacting fashion. It also comes with a great and timely introduction by Warren Ellis that came out before the election but seems spot-on after, and some supplemental materials at the end that explored Sterling’s writing of the book. This latter appealed directly to the process voyeur in me and I’d love to see it in more works.

PIRATE UTOPIA.: Highly Recommended Reading.

THE LAST BASTILLE BLOG reprints Hakim Bey’s famed 1991 essay “Temporary Autonomous Zones” which made references to Pirate Utopias, Bruce Sterling, and Fiume.

THE SEA-ROVERS AND CORSAIRS of the 18th century created an “information network” that spanned the globe: primitive and devoted primarily to grim business, the net nevertheless functioned admirably. Scattered throughout the net were islands, remote hideouts where ships could be watered and provisioned, booty traded for luxuries and necessities. Some of these islands supported “intentional communities,” whole mini-societies living consciously outside the law and determined to keep it up, even if only for a short but merry life. Some years ago I looked through a lot of secondary material on piracy hoping to find a study of these enclaves–but it appeared as if no historian has yet found them worthy of analysis. (William Burroughs has mentioned the subject, as did the late British anarchist Larry Law–but no systematic research has been carried out.) I retreated to primary sources and constructed my own theory, some aspects of which will be discussed in this essay. I called the settlements “Pirate Utopias.”

Recently Bruce Sterling, one of the leading exponents of Cyberpunk science fiction, published a near-future romance based on the assumption that the decay of political systems will lead to a decentralized proliferation of experiments in living: giant worker-owned corporations, independent enclaves devoted to “data piracy,” Green-Social-Democrat enclaves, Zerowork enclaves, anarchist liberated zones, etc. The information economy which supports this diversity is called the Net; the enclaves (and the book’s title) are Islands in the Net.

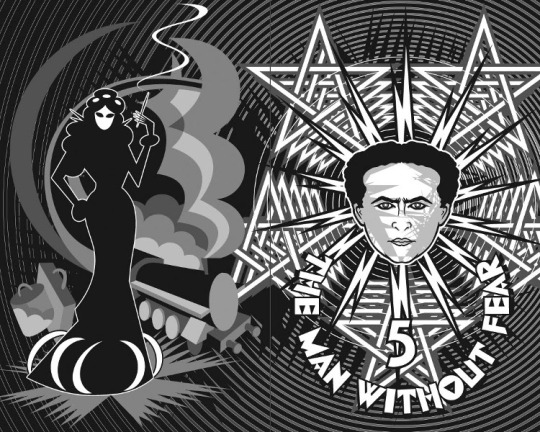

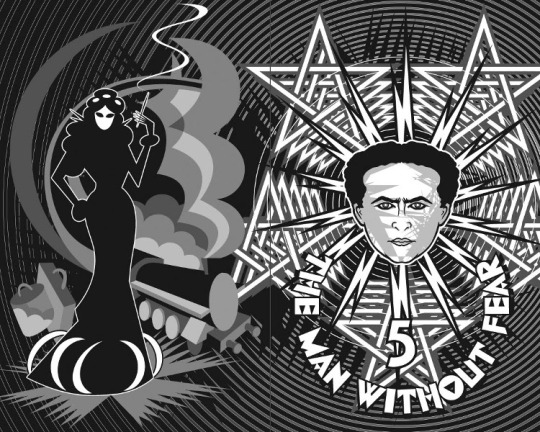

Therefore, from among the experiments of the inter-War period I’ll concentrate instead on the madcap Republic of Fiume, which is much less well known, and was not meant to endure. Gabriele D’Annunzio, Decadent poet, artist, musician, aesthete, womanizer, pioneer daredevil aeronautist, black magician, genius and cad, emerged from World War I as a hero with a small army at his beck and command: the “Arditi.” At a loss for adventure, he decided to capture the city of Fiume from Yugoslavia and give it to Italy. After a necromantic ceremony with his mistress in a cemetery in Venice he set out to conquer Fiume, and succeeded without any trouble to speak of. But Italy turned down his generous offer; the Prime Minister called him a fool.

In a huff, D’Annunzio decided to declare independence and see how long he could get away with it. He and one of his anarchist friends wrote the Constitution, which declared music to be the central principle of the State. The Navy (made up of deserters and Milanese anarchist maritime unionists) named themselves the Uscochi, after the long- vanished pirates who once lived on local offshore islands and preyed on Venetian and Ottoman shipping. The modern Uscochi succeeded in some wild coups: several rich Italian merchant vessels suddenly gave the Republic a future: money in the coffers! Artists, bohemians, adventurers, anarchists (D’Annunzio corresponded with Malatesta), fugitives and Stateless refugees, homosexuals, military dandies (the uniform was black with pirate skull-&-crossbones–later stolen by the SS), and crank reformers of every stripe (including Buddhists, Theosophists and Vedantists) began to show up at Fiume in droves. The party never stopped. Every morning D’Annunzio read poetry and manifestos from his balcony; every evening a concert, then fireworks. This made up the entire activity of the government. Eighteen months later, when the wine and money had run out and the Italian fleet finally showed up and lobbed a few shells at the Municipal Palace, no one had the energy to resist.

D’Annunzio, like many Italian anarchists, later veered toward fascism–in fact, Mussolini (the ex-Syndicalist) himself seduced the poet along that route. By the time D’Annunzio realized his error it was too late: he was too old and sick. But Il Duce had him killed anyway–pushed off a balcony–and turned him into a “martyr.” As for Fiume, though it lacked the seriousness of the free Ukraine or Barcelona, it can probably teach us more about certain aspects of our quest. It was in some ways the last of the pirate utopias (or the only modern example)–in other ways, perhaps, it was very nearly the first modern TAZ.

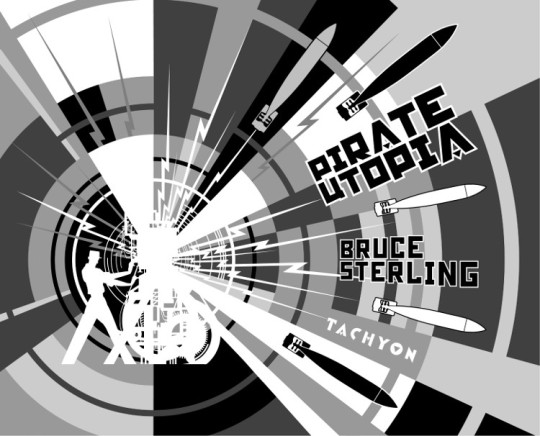

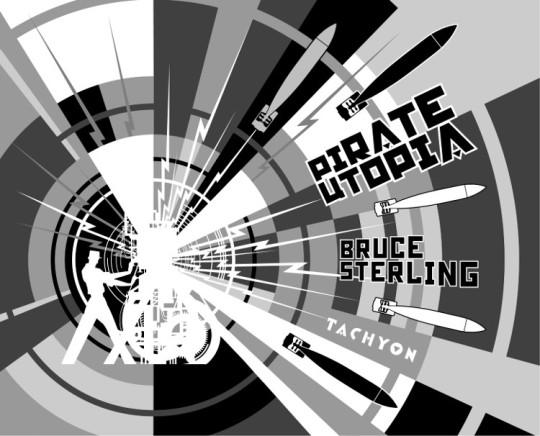

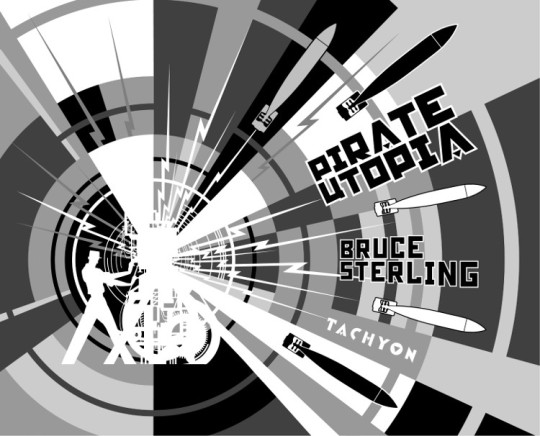

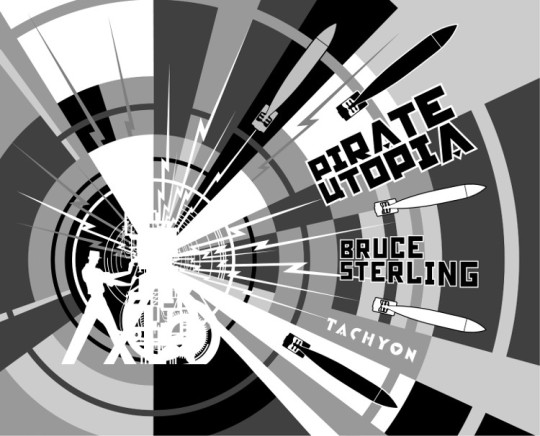

For more info on PIRATE UTOPIA, visit the Tachyon page.

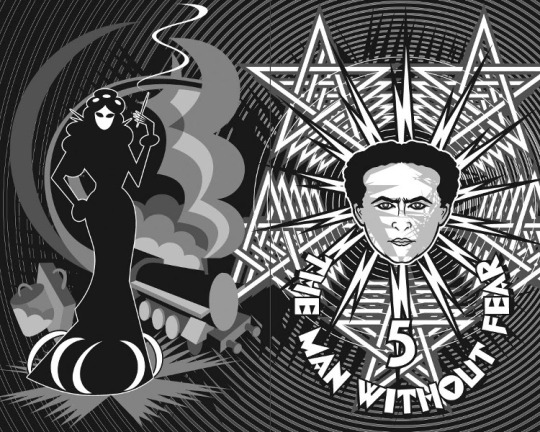

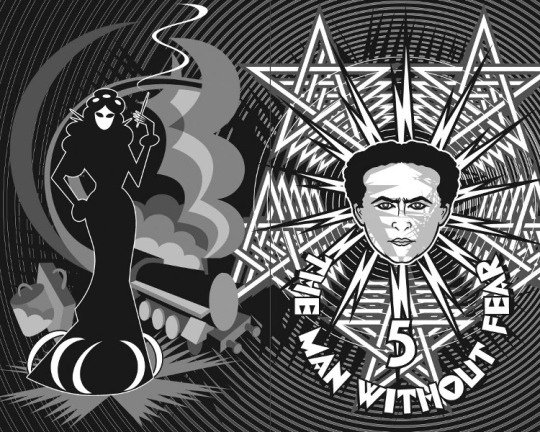

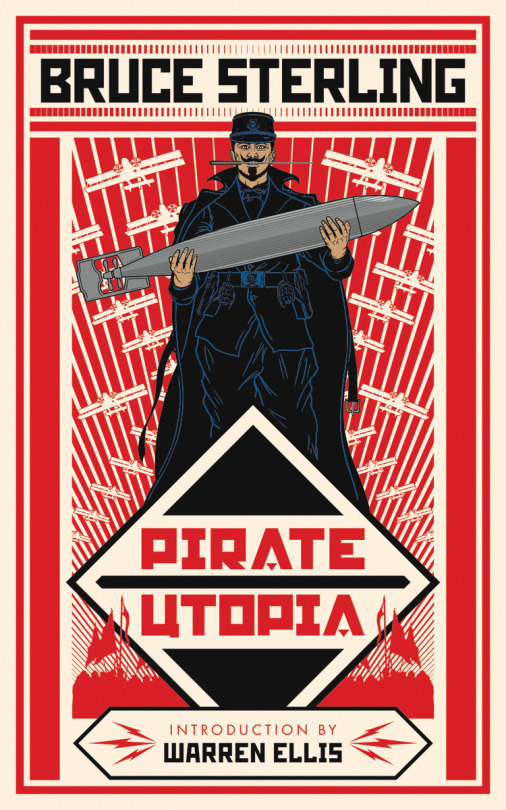

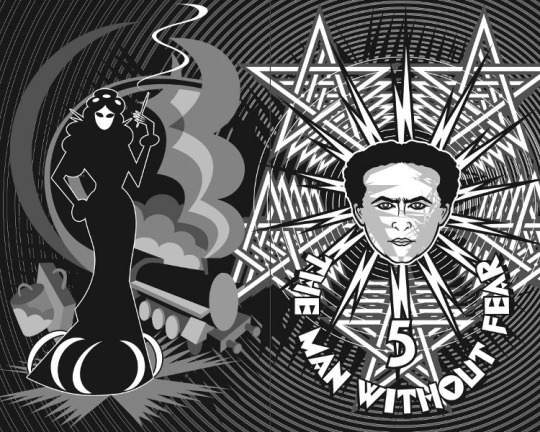

Cover and illustrations by John Coulthart