Tachyon tidbits featuring Brandon Sanderson, Bruce Sterling, Lauren Beukes, Hannu Rajaniemi, and Alastair Reynolds

The latest reviews and mentions of Tachyon titles and authors from around the web.

Brandon Sanderson (credit: Ceridwen via Wikimedia Commons), Bruce Sterling, Lauren Beukes, Hannu Rajaniemi, and Alastair Reynolds (Barbara Bella)

MAESTOSO praises Brandon Sanderson’s Hugo Award winner THE EMPEROR’S SOUL and Bruce Sterling’s Sidewise Award-nominated PIRATE UTOPIA.

A very quick and flowing read, and one filled with a deceptively rich world (no easy feat for a book that I polished off in one sitting!) and intricate laws of magic that capture the imagination. Shai is a delightfully unreliable narrator, and I feel as beguiled and enchanted by her as I’m sure Gaotona did. A solid work of fantasy fiction.

Goodreads Rating: 4/5 stars

My favorite read of 2017, and my only regret is that I hadn’t read this sooner. Phenomenal world-building, good pulpy rewrites (or reimagining) of real historical events, and all the dieselpunk to last me years. Post-WWI Italy lends itself well to this sort of fantastic non-fantasy writing, and Pirate Utopia does not disappoint with its surging factions, its larger-than-life characters, and its complete disregard for what is real and what is merely possible.

Goodreads Rating: 5/5 stars

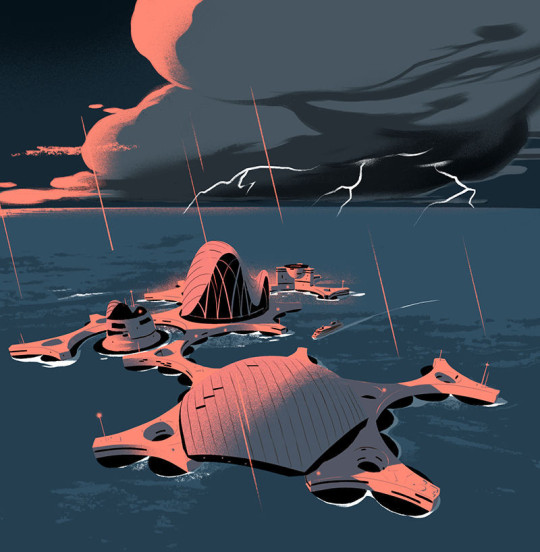

Illustration by Señor Salme

Lauren Beukes, Hannu Rajaniemi, and Alastair Reynolds contribute to NATURE’s “Science fiction when the future is now.”

AlphaGo, fake news, cyberwar: 2017 has felt science-fictional in the here and now. Space settlement and sea-steading seem just around the bend; so, at times, do nuclear war and pandemic. With technological change cranked up to warp speed and day-to-day life smacking of dystopia, where does science fiction go? Has mainstream fiction taken up the baton?

Nature asked six prominent sci-fi writers — Lauren Beukes, Kim Stanley Robinson, Ken Liu, Hannu Rajaniemi, Alastair Reynolds and Aliette de Bodard — to reflect on what the genre has to offer at the end of an extraordinary year.

LAUREN BEUKES: The power of Afrofuturism

Is science fiction relevant in an age of catastrophic climate change, the refugee crisis and the rise of the far right? Yes: not for what it predicts about the future of the world, but for how it unpacks who we are in it.

In her 1973 short story ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’, novelist Ursula K. Le Guin wrote about a fictional utopia that came at a terrible cost everyone knew about: a single child tortured in a room underneath the city, in the filth and the dark, to pay for their happiness.

For me, Omelas is a compelling way of understanding the world I grew up in, as a white South African under apartheid. White people make up only around 9% of the population, but, until 1994, they held the rest of the country hostage under a racist, inhumane and violent regime that forced people of colour into indentured labour and inferior schools, and responded to resistance with tear gas and shootings, hit squads and torture farms.

Science fiction allows us the distance to circumvent issue fatigue in our very troubled times. We can play out ideas and scenarios because we are creatures of parable and myth and allegory, TED talks and ethical trolley problems. Fiction is how we grapple with ourselves. By imagining the unimaginable, it’s possible to make reality more bearable.

Illustration by Señor Salme

HANNU RAJANIEMI: Making stranger worlds

In the Netflix programme Stranger Things, a nostalgia-tinged small town in 1980s America is attacked by supernatural forces. To make sense of what is happening, the preteen protagonists turn to the classic game Dungeons & Dragons and name the invading monsters after creatures from it.

Our world, too, is undergoing an invasion of the strange. An algorithm became capable of defeating the best human players of 2,500-year-old board game Go after three days of playing itself. Gene drives may soon spread population-suppressing genes to malaria-carrying mosquitoes. And at least one Silicon Valley plutocrat has a good chance of being buried on Mars. It’s not surprising that the media calls on iconic sci‑fi figures to describe these developments — a recurring cast that includes the Terminator, Frankenstein and Iron Man.

Working scientists scoff at such comparisons, knowing how fragile early experiments and nascent technologies can be. Some scientists I’ve come to know in both my academic and biotechnology start-up careers develop a gag reflex to science fiction, weary of trying to describe their work against a backdrop of preconceived notions. Yet science fiction can help both scientists and non-scientists to comprehend each other and make sense of our topsy-turvy era.

To understand how, we must look beyond sci-fi’s worn tropes, to how we read it. In science fiction, as in all fiction, you get to be someone else — but the imaginary world around you is also unfamiliar, inviting you to learn its rules from the inside. The reader has to engage in active sense-making, with the author’s implicit assurance that there is a discoverable underlying order. When that happens, there is often a transcendent, goosebumpy moment that opens still greater vistas beyond the page, in the reader’s imagination.

Illustration by Señor Salme

ALASTAIR REYNOLDS: The bards of turbulence

In a science-fictional present, thinking about futures can feel difficult. This year, when the AlphaGo algorithm designed by Google’s DeepMind beat the world’s best human Go player — something long assumed to be beyond the capabilities of artificial intelligence — it was hard not to feel that a corner had been turned. And so much else has become normalized: human–pig hybrid embryos, commercial spaceflight, neuroprosthetics, cyberwarfare. Not far off loom wild cards from global pandemics to head transplants, hyperloops and sea-steading.With a present this intractable, some might say that science fiction as a serious speculative enterprise has had its day.

Consider, however, the science-fiction writer of a century ago, surveying her world at the cusp of 1918 and trying to think cogently about the coming era. The preceding decades would have felt to her like an ever-accelerating stampede of scientific, technological and sociological upheavals.Within living memory, steam power had vanquished the ‘age of fighting sail’. Electricity had begun to supplant gas as the means of lighting cities. Cars and trucks were displacing horses; mechanized warfare was taking over on the battlefield (the tank first saw service in 1916). A transatlantic telegraph system — the first piece of global telecommunications infrastructure — had existed since 1858. But it was already looking old-fashioned next to the wireless telegraphy and radio developed by Guglielmo Marconi and others, including Reginald Fessenden, who first demonstrated wireless voice transmission in 1900. Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity would shortly pass its first experimental test, even as the quantum revolution gathered pace.

The writer would have been aware of other discoveries with daunting ramifications. Among these were subatomic structure, evidence of 500-million-year-old ecosystems in the Canadian Burgess Shale fossils, and chemist Fritz Haber’s experiments in nitrogen fixation — as well as Thomas Hunt Morgan’s explorations of genes as unique units of inheritance in fruit flies, and Alfred Wegener’s revelation of continental drift. News on each emerged in dizzying succession.

The future could hardly have looked less assured, the present less tractable. Yet it is precisely this period of change and uncertainty that gave birth to science fiction as a mass cultural phenomenon.

For more on THE EMPEROR’S SOUL, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover art by Alexander Nanitchkov

Design by Elizabeth Story

For more info on PIRATE UTOPIA, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by John Coulthart