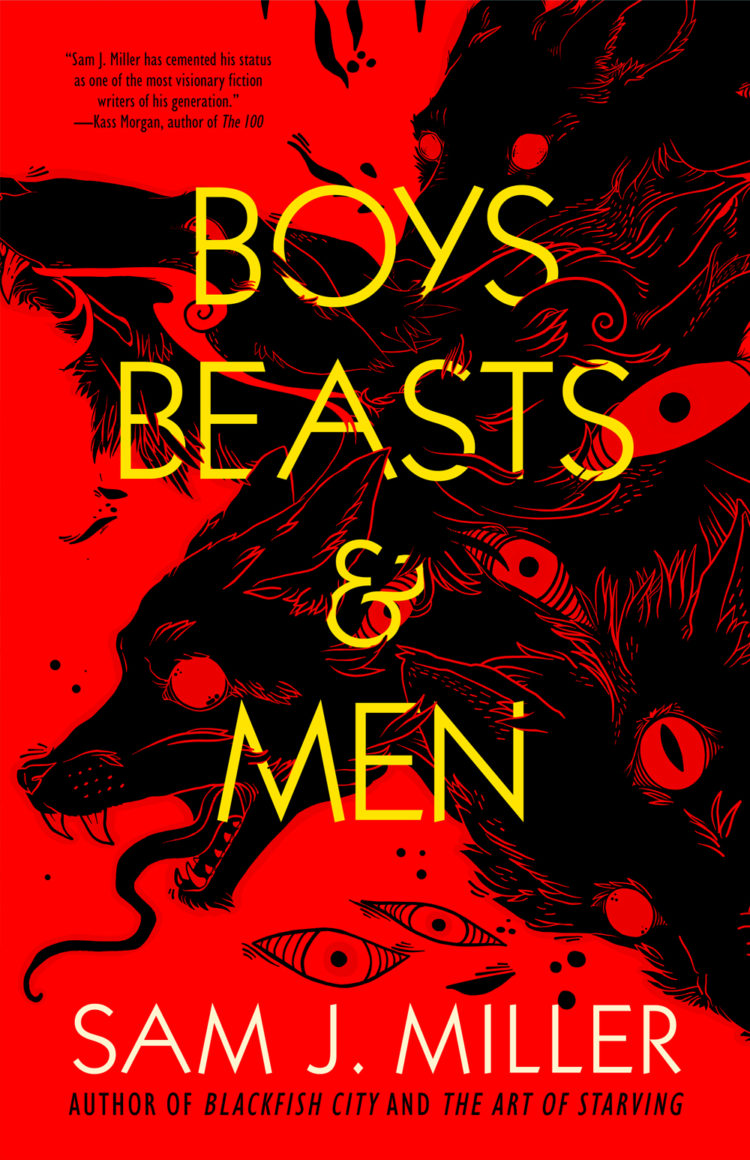

BOYS, BEASTS & MEN by the award-winning Sam J. Miller preview: “Shattered Sidewalks of the Human Heart”

In celebration of the release of Sam J. Miller’s debut collection BOYS, BEASTS & MEN, Tachyon presents glimpses from the new collection.

[STARRED REVIEW] Finding danger and humanity in their characters, the short stories of Boys, Beasts & Men marry emotional epiphanies with violence, resulting in imaginative, stirring meditations on LGBTQ+ struggles and acceptance.

—Foreword

Design by Elizabeth Story

Shattered Sidewalks of the Human Heart

by

Sam J. Miller

Strange that I didn’t see who she was when she stood in the street, arm upraised, headlights strobing her like flashbulbs, exactly as she’d appeared in the publicity stills that papered New York City for one whole summer. Only when she got in the cab and told me where she was going and slumped back in the seat, and I looked in the mirror and saw the look of utter exhaustion and emptiness fill her face—only then did it click.

“You’re her,” I said, breath hitching.

“I’m somebody,” she said, weary, clearly gut-sick of having this conversation, but I couldn’t stop myself.

“You’re Ann Darrow.”

“The one and only.”

And maybe I had recognized her, on some unconscious level, because I hadn’t meant to pick up any passengers when I got in my cab and started driving. Friday nights I’d sometimes hit up the Ziegfeld, the Palace, drive in circles to see the movie stars arriving at their premieres, and, later on, leaving, and later still staggering out of their afterparties. Purely recreational, usually, but that night it was downright medicinal. I needed that glamour, those sixty-karat smiles, the wonder in the eyes of the crowd. The lie of a beautiful world.

Bombs were falling, four thousand miles away. Crematoria were being kindled.

I pulled away from the curb. One of her posters was framed on the wall of the room I rented. The only decorative touch that had followed me through all five of the boarding houses I’d lived in since getting kicked out of the house. Ann Darrow, eyes wide with terror, arm upraised to fend off something monstrous. A massive black outline hulked behind her. Art deco lettering beneath her blared KONG: THE EIGHTH WONDER OF THE WORLD.

“You Jewish?” she asked.

“I am,” I said, tracing my profile in the rearview mirror. “The nose gave it away?”

“The eyes,” she said. “The only people who look really scared today are Jewish.”

It took me an awful long time to say, “That’s because most people have no idea what horrible things human beings are capable of,” and even once I said it it wasn’t quite right, didn’t quite capture the rich flavor of my fear, my rage.

“Some of us do,” she said. “Some of us know exactly.”

“I’m Solomon,” I said.

“That why your radio’s switched off, Solomon?”

“Yeah, sorry. Couldn’t stand to hear it one more time. I can turn it back on if you want to listen to something.”

“No,” she said. “That’s one of several things I’m trying not to think about tonight.”

September 1st, 1939. At 4:45 that morning, Germany had invaded Poland. Word was, England and France would be declaring war within the week. Not that anyone expected them to lift too many fingers to save the millions of Jews in Poland.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Forgot to ask—where you heading?”

“Just drive,” she said. “I’ll figure something out.”

“You coming from a movie premiere?”

“Yeah,” she said. “The Women. It had its moments. They love to have notorious floozies and disgraced politicians show up on the red carpet. Who am I to turn down free food and alcohol?”

Normally, my New York City cabdriver cool prevailed. Even with only five years driving under my belt, I’d already had more movie stars in my backseat than there were cross streets in Manhattan. But this was no movie star. No fraudulent sorcerer, whose magic was made up of lighting and make-up and special effects and screenwriting. This was Ann Darrow. This was someone who knew what magic was. Who’d been held in its hand. Who’d been lifted high into the sky by it, and then watched it die.

“Let me guess,” she said, catching my repeated mirror glances. “You were there that night. You were in the theater. You’re a baby, you would have been, what, twelve?”

“Twelve exactly,” I said, startled. Most people pegged me for far older. I’d been driving a cab on New York City streets since I was thirteen, and nobody’d ever batted an eyelash at it. “But I wasn’t in the theater that night.”

“I know,” she said. “Somebody tells me they were, I know they’re lying. Swear to god, you add up all the people who’ve told me they were there that night, there were a couple million people in the audience. Place only had a thousand seats, and half of them were empty. People make it seem like Denham was some kind of genius promoter, but that piece of shit was as bad at that as he was at everything else.”

I had so many questions. For years I’d dreamed of this moment. Now my words were nowhere to be found.

“Let me guess,” she said. “You want to know about . . . him.”

“Yeah.”

She rolled her eyes.

She wasn’t that much older than me. She’d been twenty, when she traveled to Skull Island. But those events, and the six years since then, had accelerated her aging. From her purse, she pulled a bottle and a glass. Not a flask; a glass, in her purse. “You want a drink, Solomon?”

“Not while I’m driving.”

“Where are your people from, Solomon?”

“Poland,” I said.

She cursed, so softly I couldn’t hear which one. “You got people over there still?”

“Three grandparents.”

“Oh, honey,” she said, one hand reaching forward to touch my shoulder.

She was kind. That much was true. I’d imagined her in the hold of the ship, comforting Kong in his chains and his seasickness. Backstage, calming him down while tiny men flashed cameras in his helpless face. Eighty stories up, pleading with him to pick her back up, trying to tell him that the airplanes wouldn’t shoot him while he was holding her. Angry at him for not understanding her, or for understanding and not wanting to put her at risk.