THE CUTTING ROOM coming attraction: “Final Girl Theory” by A. C. Wise

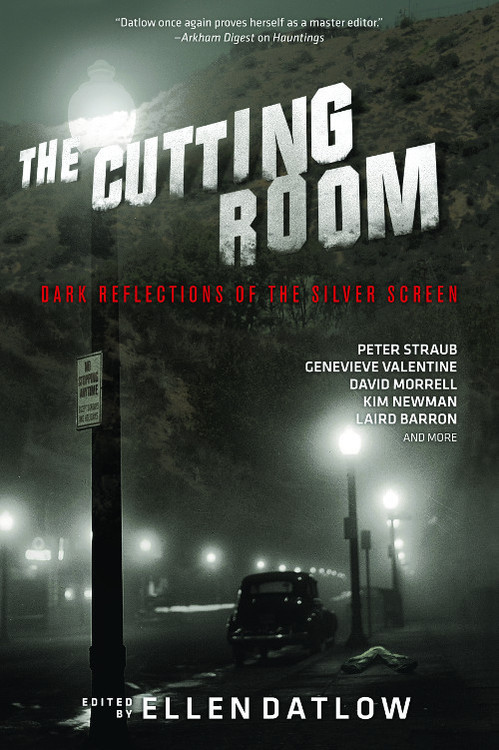

Over the next two weeks, in celebration of Halloween and the new anthology The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the Silver Screen, Tachyon and editor Ellen Datlow present excerpts from a selection of the volume’s horrifying tales.

Today’s selection comes from “Final Girl Theory” by A. C. Wise.

Everyone knows the opening sequence of Kaleidoscope. Even if they’ve never seen any other part of the movie (and they have, even if they won’t admit it), they know the opening scene. No matter what anyone tells you, it is the most famous two-and-a-half minutes ever put on film.

The camera is focused on a man’s hand. He’s holding a small shard of green glass, no bigger than his fingernail. He tilts it, catching the light, which darts like a crazed firefly. Then, so very carefully and with loving slowness, he presses the glass into something soft and white.

The camera is so tight the viewer can’t see what he’s pushing the glass into (but they suspect). Can you imagine that moment of realization for someone who doesn’t know? Watch the opening sequence with a Kaleidoscope virgin sometime, you’ll understand. The man pushes the glass into the soft white, and moves his hand away. A bead of bright red blood appears.

As the blood threads away from the glass, the sound kicks in. Only then do most people notice its absence before and discover how unsettling silence can be. The first sound is a breath. Or is it? Kaleidophiles (yes, they really call themselves that) have worn out old copies of the film playing that split-second transition from silence to sound over and over again. They’ve stripped their throats raw arguing. Does someone catch their breath, and if so, who?

There are varying theories, the two most popular being the man with the glass and the director. The third, of course, is that the man with the glass and the director are the same person.

Breath or no breath, the viewer slowly becomes aware they are listening to the sound of muffled sobs. At that moment of realization, as if prompted by it, thus making the viewer complicit right from the start, the camera swings up wildly. We see a woman’s wide, rolling eyes, circled with too much makeup. The camera jerk-pans down to her mouth; it’s stuffed with a dirty rag.

The soundtrack comes up full force—blaring terrible horns and dissonant chords. The notes jangle one against the next. It isn’t music, it’s instruments screaming. It’s sound felt in your back teeth and at the base of your spine.

The camera zooms out, showing the woman spread-eagle and naked, tied to a massive wheel. Her skin is filled with hundreds of pieces of colored glass—red, blue, yellow, green. Her tormentor steps back; the viewer never sees his face. He rips the gag out, and spins the wheel. Thousands of firefly glints dazzle the camera.

The woman screams. The screen dissolves in a mass of spinning color, and the opening credits roll.

You know what the worst part is? The opening sequence has nothing to do with the rest of the film. It is what it is; it exists purely for its own sake.

But let’s go back to the scream. It’s important. It starts out high-pitched, classic scream queen, and devolves into something ragged, wet, and bubbling. If there was any nagging doubt left about what kind of movie Kaleidoscope really is, it’s gone. But it’s too late. Remember, the viewer is complicit; they agreed to everything that follows in that split second between silence and sound, between sob and catch of breath. They can’t turn back—not that anyone really tries.

Here’s another thing about Kaleidoscope—no one ever watches it just once; don’t let them tell you otherwise.

The opening is followed by eighty-five minutes of color-soaked, blood-drenched action. (Except—if you’re paying attention—you know that’s a lie.)

The movie is a cult classic. It’s shown on football fields, on giant, impromptu screens made of sheets strung between goalposts. It flickers in midnight double-feature theaters, lurid colors washing over men and women hunched and sweating in the dark, feet stuck to crackling floors, breathing air reeking of stale popcorn. It plays in the background, miniaturized on ghostly television screens, while burnouts fuck at 3 a.m., lit by candles meant to disguise the scent of beer and pot.

Here’s the real secret: Kaleidoscope isn’t a movie, it’s an infection, whispered from mouth to mouth in the dark.

Hardcore fans have every line memorized (not that there are many). They know the plot back and forth (though there isn’t one of those, either). You see, that’s the beauty of Kaleidoscope, its terrible genius. It is the most famous eighty-seven-and-a-half minutes ever committed to film (don’t ever let anyone tell you otherwise), but it doesn’t exist. If you were to creep through the film, frame by frame (and people have), you would know this is true.

Kaleidoscope exists in people’s minds. It exists in the brief, flickering space between frames. The real movie screen is the inside of their eyelids, the back of their skulls when they close their eyes and try to sleep. When the film rolls, there is action and blood, sex and drugs, and not a little touch of madness, but there are shadows, too. There are things seen from the corner of the eye, and that’s where the true movie lies. There, and in the rumors.

For information on The Cutting Room: Dark Reflections of the SilverScreen, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover by Josh Beatman.