PIRATE UTOPIA pushes the envelope

At ASIMOV’S SCIENCE FICTION, Peter Heck is intrigued by Bruce Sterling’s PIRATE UTOPIA.

Sterling’s novel, loosely based on actual history, follows Lorenzo Secondari, an Italian war veteran who dreams of creating an airborne radio-guided torpedo—essentially a guided missile. The plot is episodic, as Secondari interacts with various members of the ruling clique—who improve on their historical models by planning to conquer not just Italy but the world. To that end, they form alliances with Mussolini, who is just beginning to cause a stir in Italy, and a German fringe group that readers will recognize as the early Nazi party.

In addition to his dream of aerial torpedoes, Secondari finds himself involved with a local woman, Blanka Piffer, a Communist union leader who becomes dictator of the torpedo factory. With Blanka’s young daughter Maria, Secondari comes to understand that the twentieth century will be something completely new—and that the Futurists’ vision of that new world is perhaps not entirely trustworthy.

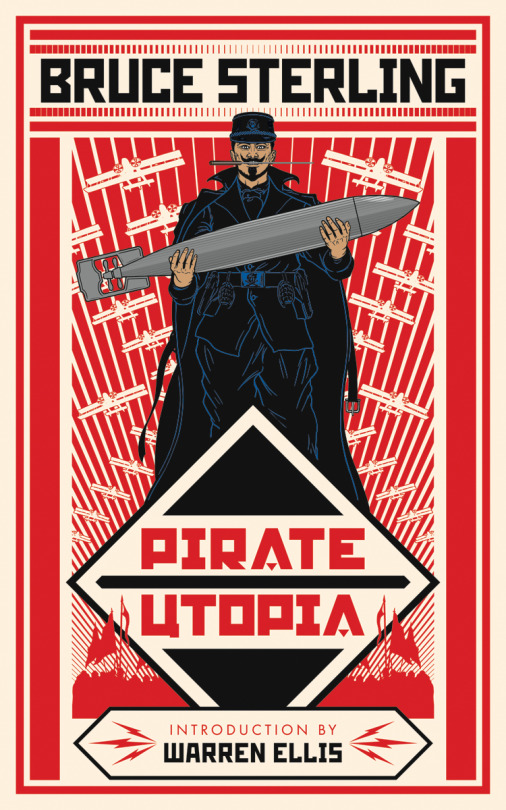

In addition to the main text, the book includes period-appropriate illustrations by John Coulthart, an introduction by Warren Ellis, and an interview with Sterling in which he discusses the historical Carnaro and its place in history. If you’re looking for something off the beaten track, check out this provocative venture by a writer who isn’t afraid to push the envelope.

The overall package enthralls MARZAAT.

Now, these problems are all solved in the Tachyon package which supplements Sterling’s story. In effect, it supplies meaning and context for Sterling’s truncated story.

For instance, in an included interview with Rick Klaw, Sterling provides the story’s theme: “… the brotherly feeling between certain kinds of political ecstatic cult politics and the ‘sense of wonder’ of reality-bending science fiction”.

Christopher Brown’s concluding essay, “To the Fiume Station”, puts the Republic of Carnaro in the context of “Sterling’s recent observations about the ways network culture liberates the timeline of our minds from the constraints of historiographically sanctioned narratives”. In particular, he mentions Sterling’s thematically similar Islands in the Net. However, the older Sterling seems wiser and more restrained in the possibilities of these semi-utopian schemes and about the wisdom of technological engineers managing our political affairs. Though, to judge by the attention we pay Zuckerberg, Gates, and Musk and have brought engineering terms like “hack” into politics, evidently we are a long way from shunning the technocratic state by and for technocrats.

Graphic novelist Warren Ellis’s introduction sets things up with a good introduction about “old gunsmoke, exterminating art and war dreams within which” Sterling presents his story.

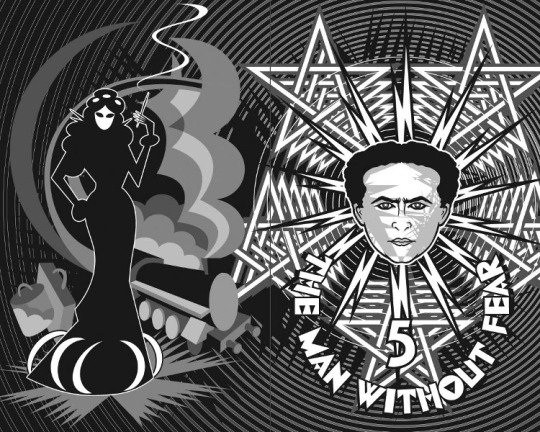

Illustrator John Coulthart provides some quite nice illustrations throughout the book inspired by Futurism and D’Annunzio’s symbols.

In short, as a self-contained work, Sterling’s story is something of a disappointment. But, as a total package, this book is worth picking up.

For more info on PIRATE UTOPIA, visit the Tachyon page.

Cover and illustrations by John Coulthart