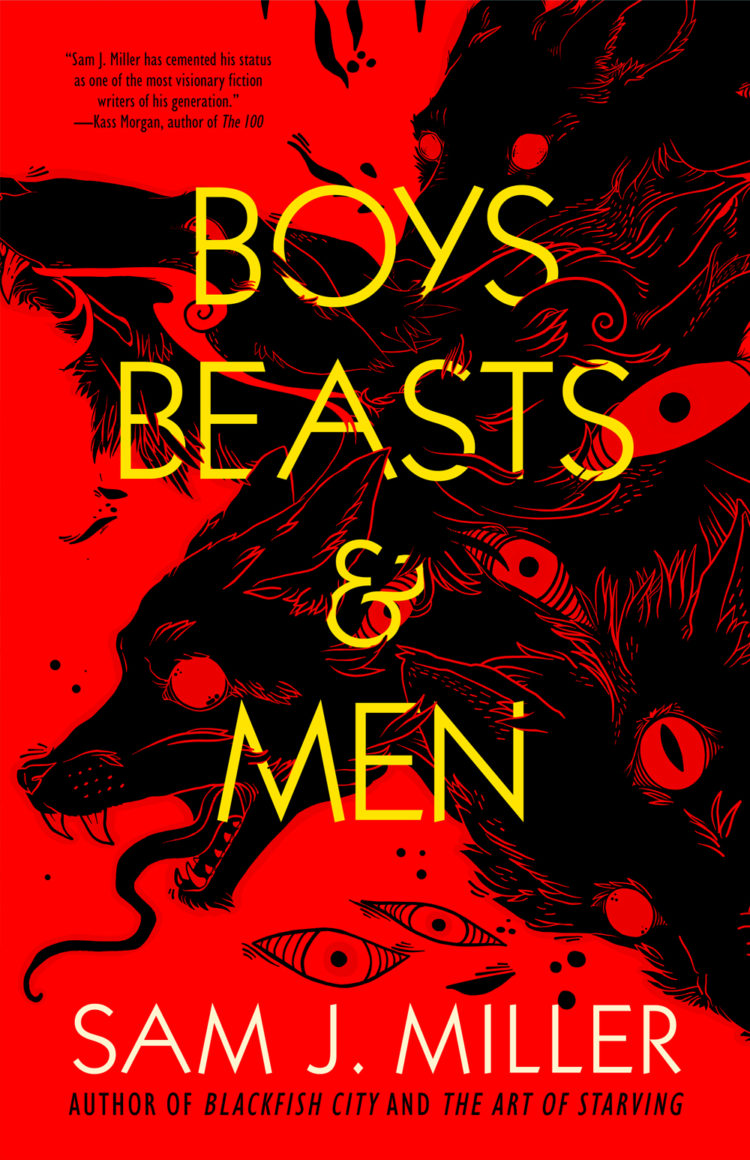

BOYS, BEASTS & MEN by the award-winning Sam J. Miller preview: “Allosaurus Burgers”

In celebration of the release of Sam J. Miller’s debut collection BOYS, BEASTS & MEN, Tachyon presents glimpses from the new collection.

Sam Miller is my hero: a fearless visionary whose stories are at once vivid, electrifying, brutal, and full of heart. Oh, the heat of them.

—Sarah Pinsker, author of A Song For A New Day and Sooner or Later Everything Falls Into the Sea

Design by Elizabeth Story

Allosaurus Burgers

by

Sam J. Miller

I thought my mother was God, then. Six-foot-something, all flesh and freckles, she towered over our neighbors in church and at the supermarket. She came home from the slaughterhouse smelling like blood. I was nine then, and she could still pick me up, hoist me into the air. Not even the fathers of the other boys my age could do that. She wasn’t afraid of anything.

At breakfast that morning my mother had said, “Day after tomorrow, the army’s going to take it away, and I personally think it can’t happen soon enough.”

I finished my milk and Mom poured me more, which I did not want, which I drank. Mom is certain that the government wants to take our stuff. Mostly our guns. She has a lot of guns and a lot of stickers on her car about them and her cold dead hands. So now I wondered why she wanted them to take the allosaurus.

“Woulda taken it right away, only it’ll take ’em forty-eight hours to scrounge up the right equipment.”

I nodded. Mom drank from the jug and put it back in the fridge.

“Blecher’s going to make out okay, though. Heard he’s got a million in TV deals lined up.” She likes Mr. Blecher because he’s an old, old man, but he can still get over on her once in a while in arm wrestling. “And he’s hidden away some of its droppings to sell to the companies.”

“What kind of companies?”

Mom frowned. “How the hell would I know something like that?”

I wondered what they would do with dinosaur poop. Could you clone something from its poop? Could something so gone forever come back so easily? And if poop worked, what else would? I thought of my father’s baseball cap, the one Mom didn’t know I had, the one that still smelled of his sweat when I crawled to the back of my closet late at night and in total darkness buried my nose in it.

Mom never sits at mealtimes. She made anxious circles through the tiny kitchen, moving refrigerator magnets and removing expired coupons and straightening the cat and dog figurines I could never stop forcing to fight each other. It was a Tuesday morning, which is when my sister Sue calls from college. Waiting for the call always made Mom a little tense.

“What?” she said, kicking me lightly. “Why the face, like I just killed a puppy?”

I shrugged.

“You want me to be excited about it. But that thing ain’t right. They got scientists out combing that corner of Blecher’s farm, but mark my words they won’t find nothing. This is something bigger than science.”

“At church yesterday, Pastor said it’s a creature of God,” I spoke carefully, not contradicting, just seeking clarity. I could no longer swing my legs when I sat at the kitchen table. This was a recent development, one I’d been looking forward to that had turned out to be pretty crummy. My feet rested resentfully on the cold tiles. A draft came from under the door.

“Pastor’ll say what needs to be said to help Mr. Blecher out and to get people to come and spend their money in town. Creature of God, my foot.”

Church was the most important thing in my mother’s life, but I don’t think she believed in God. The Hudson Falls Evangelical Lutheran Church gave her lots of things, like friends and a full social calendar and a reason not to go to the liquor store. God didn’t offer her anything extra. Mostly she just liked what Pastor said: the sermons full of blood, fire, and the devil and impending doom, about a world gone haywire and full of sinners and about to be punished.

She heaped bacon on my plate, five then six then seven slices. “’Fore you know it, there’ll be bunches of them things, running riot over all the world. Eating us all up.”

“It’s locked up, Mom.”

“I know you saw King Kong, because I saw you crying at the end of it”—and she thumped me on the arm, not hard, because I saw her cry too when the big ape fell—“so I know you know they had Kong tied up good and proper, and he still got loose.”

My sister Sue called then. Mom talked to her for a little while, not sounding super-excited. Mom handed me the phone while Sue was in a sentence.

“Hi,” I said, interrupting her.

“Matt? Hi! Exciting stuff, right? A dinosaur in stupid little Hudson Falls! It’s on all the news channels.”

“Yeah.”

“Have you seen it?”

“No,” I said. “We go today.”

“I wish I could come see it, but it’ll be gone soon, right? Did you read the dinosaur books I sent you?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

I shrugged.

“Did you just shrug? You can’t shrug over the phone.”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Do you not like dinosaurs anymore?”

I shrugged again. Then I remembered about shrugging. “I don’t know.”